How the New York Times puts words and images together

Photoville, located under the Brooklyn Bridge photo (c) Sarah Coleman

Ah, Photoville , I look forward to you every year. Balmy waterfront, Brooklyn hipsters, shipping containers with all kinds of interesting photo exhibits. Panels and workshops; nighttime shows in the beer garden with Manhattan glittering in the background. You know how to show a girl a good time.

Last Friday, I ventured out to Brooklyn Bridge Park for Photoville’s sixth outing and An Evening with the New York Times . Our city’s standard-bearing paper has enormous worldwide reach and influence, and its choices of both words and images can sway everything from fashion trends to foreign policy. How do New York Times editors balance text and imagery, and how do the paper’s photographers balance their responsibilities? This nighttime presentation offered to shed a bit of light on how the (gourmet) sausage gets made.

The presentation was eclectic, featuring three very different photojournalists and also a viewing of an unusual project that the Times published this summer, America Today, in Vision and Verse , where editors selected six poems by contemporary American poets and asked six photographers to let the poems inspire them.

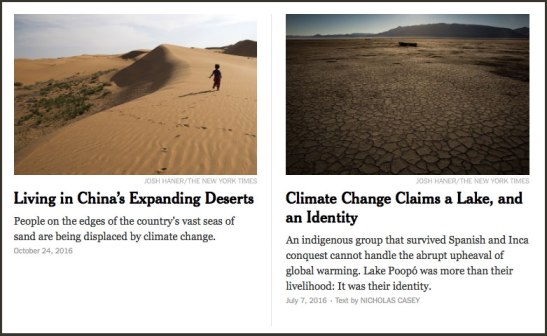

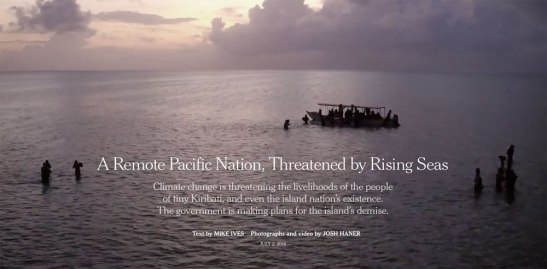

Though subject to the funding issues that plague all newspapers today, the

Times

still has the resources to front a project like Josh Haner’s ambitious

Carbon’s Casualties

, a series of eight visually innovative stories about climate change refugees across five countries. A

Times

staffer, Haner showed one of these stories and said that he had wanted to get away from the typical kind of imagery associated with climate change: “glaciers calving into the ocean and polar bears on a piece of ice floating in the sea.” To do this, he and

Times

bureaus over the world researched places where climate change is forcing relocations or drastic shifts. Then, to increase the stories’ impact, he photographed them with drone cameras that produced big, dramatic video overviews.

Though subject to the funding issues that plague all newspapers today, the

Times

still has the resources to front a project like Josh Haner’s ambitious

Carbon’s Casualties

, a series of eight visually innovative stories about climate change refugees across five countries. A

Times

staffer, Haner showed one of these stories and said that he had wanted to get away from the typical kind of imagery associated with climate change: “glaciers calving into the ocean and polar bears on a piece of ice floating in the sea.” To do this, he and

Times

bureaus over the world researched places where climate change is forcing relocations or drastic shifts. Then, to increase the stories’ impact, he photographed them with drone cameras that produced big, dramatic video overviews.

On the paper’s

Lens

blog, Haner

recounts

that the drone photography “created a sort of visual eye candy that we thought would make people want to explore articles that were covering complex themes through nuanced writing.” Unlike with some stories, where the photographer is essentially illustrating a written story, words and images were given equal weight, so that, as Haner says, “the visual reporting itself contributed to the stories.”

On the paper’s

Lens

blog, Haner

recounts

that the drone photography “created a sort of visual eye candy that we thought would make people want to explore articles that were covering complex themes through nuanced writing.” Unlike with some stories, where the photographer is essentially illustrating a written story, words and images were given equal weight, so that, as Haner says, “the visual reporting itself contributed to the stories.”

If you haven’t seen them, I recommend that you look at these stories , which are powerful and visually stunning. Of course, they’re also sobering in the way they channel disturbing trends, from the West African men forced into migration from escalating drought, to the Inupiat people of Alaska threatened by rising ocean temperatures. In the Q&A following the presentation, I asked Haner if there had been any measurable impact from his reporting. He replied, “Sadly, there hasn’t.”

Photojournalist Meridith Kohut, who is based in Venezuela, reported different results, saying that her coverage of that country’s political and economic turmoil had led to the involvement of several international aid organizations. “The main thing we’re trying to do at the

New York Times

is to have original reporting,” she said. She was grateful that editors had given her freedom to explore the country for a year, and to discover stories that went “beyond the bread lines.” Because of that latitude, she and reporter Nicholas Casey were able to break a powerful story about

Venezuela’s crumbling mental hospitals

, one of several stories that led to her receiving the fifth annual Chris Hondros Fund Award.

Photojournalist Meridith Kohut, who is based in Venezuela, reported different results, saying that her coverage of that country’s political and economic turmoil had led to the involvement of several international aid organizations. “The main thing we’re trying to do at the

New York Times

is to have original reporting,” she said. She was grateful that editors had given her freedom to explore the country for a year, and to discover stories that went “beyond the bread lines.” Because of that latitude, she and reporter Nicholas Casey were able to break a powerful story about

Venezuela’s crumbling mental hospitals

, one of several stories that led to her receiving the fifth annual Chris Hondros Fund Award.

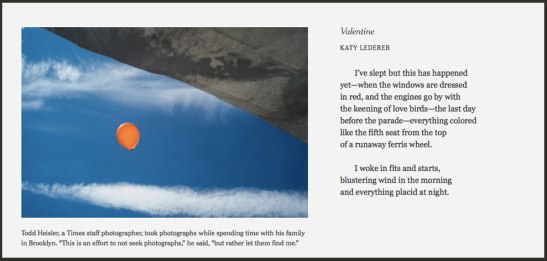

In another example of giving photographers a wide rein, the Times produced America Today, in Vision and Verse , a matching of contemporary American poems with imagery by Times staffer photographers and freelancers.

The project made specific what the New York Times strives to do with its imagery, said Deputy Photo Editor Meaghan Looram, which is to complement text rather than illustrate it. “We hear from readers that it’s much more exciting when text and image are completing each other,” she said. This goes to the heart of the Literate Lens’ own philosophy, that text and image can enhance each other and, when dancing together, tell a powerful story.

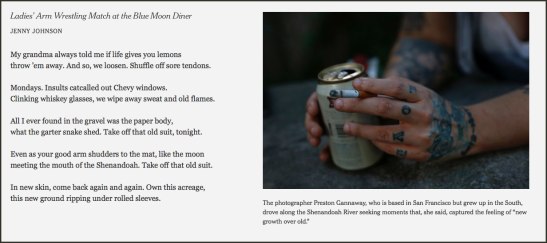

To be honest, I didn’t love any of the selected poems, but I did like that the project gave star Times photojournalists like Damon Winter and Todd Heisler a chance to explore their more experimental, lyrical sides. Panelist Preston Gannaway, who responded to the poem Ladies’ Arm Wrestling Match at the Blue Moon Diner by Jenny Johnson, said that responding had been very intuitive for her since photography and poetry were “both about feeling and emotion.” Zora J. Murff, another photographer who participated, said that the assignment had been “different, liberating, challenging.”

The evening concluded with a slideshow of political photojournalism by the newly-retired Stephen Crowley, who worked as a staff photographer for the

Times

in Washington D.C. for twenty-five years, and whose sharp eye and idiosyncratic style will be missed.

The evening concluded with a slideshow of political photojournalism by the newly-retired Stephen Crowley, who worked as a staff photographer for the

Times

in Washington D.C. for twenty-five years, and whose sharp eye and idiosyncratic style will be missed.

Clearly beloved at the paper and among photographers generally (at least judging by the capacity crowd at Photoville), Crowley fielded questions about his approach and style. He’d always tried to avoid standing in typical places, he said, and had made best use of opportunities—for example, at photo shoots in the Oval Office where Donald Trump was late “and in the meantime, Bannon’s in there, Pence shows up, and it’s a great opportunity to get other shots.”

In the Q&A session, the question arose of whether Crowley’s images—which sometimes verge on the satirical—were photojournalistic or editorial. Crowley answered this with a literary analogy, saying he thought that “readers and editors appreciate a well-turned phrase over a dry fact.” He elaborated by saying that it was about “peeling back artifice,” and that of every 10 photographs he took of a politician, he always hoped the politician might “like one, hate one, and think that the other eight were fair.”

At the end of the evening, the impression left was that the Times is blessed with the resources and talent to cover important stories, and to do so in ways that surprise and provoke. And while I’m sure that’s not always true—no large institution is without internal politics and competing interests—it’s good to know that the country’s best paper has our backs.

Photoville is open again today, tomorrow and Sunday. For a full list of programming, click here .

One comment on “ How the New York Times puts words and images together ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Very nice Sarah! Thank you !