Life in the Face of Death: A Tour with Nancy Borowick

“I’ve scrapbooked a fence in Brooklyn,” Nancy Borowick said with a laugh. It was Sunday, the second weekend of

Photoville 2017

, and the photographer was leading a walking tour of her outdoor exhibit

The Family Imprint

. People strolled by, purposeful tourists and laid-back hipsters on their way to or from the waterfront. A few lingered to look at the fifty-foot chain-link fence covered with photographs.

“I’ve scrapbooked a fence in Brooklyn,” Nancy Borowick said with a laugh. It was Sunday, the second weekend of

Photoville 2017

, and the photographer was leading a walking tour of her outdoor exhibit

The Family Imprint

. People strolled by, purposeful tourists and laid-back hipsters on their way to or from the waterfront. A few lingered to look at the fifty-foot chain-link fence covered with photographs.

The Family Imprint might have a scrapbook aesthetic, but it has nothing of the haphazard, dabbling quality that the word suggests. The project (now also a book ) is Borowick’s loving tribute to her parents, Howie and Laurel, who in 2012 were both diagnosed with terminal cancers. From this awful coincidence, Borowick drew out threads of honesty, tenderness and grace. As James Estrin wrote in his introduction to the book, The Family Imprint “is not about cancer. It is about the tender and passionate love story of her parents… the journey of a family embracing life in the face of death.”

From The Family Imprint , photograph by Nancy Borowick

I had seen and admired some of this work when it was published in the New York Times , so it was a treat to have Borowick give an intimate tour of the exhibit. She explained how, when her parents got their diagnoses in 2012 (pancreatic and breast), she made a commitment to document their journey. Traveling constantly from her home in New York City to theirs in Westchester was hard because “I was a freelancer hustling my butt off, trying to be available for various newspapers and clients.” Also hard was being both a daughter and a photojournalist, capturing her parents at their most fragile and vulnerable. But she persisted, because “friends told me I’d never regret it—that I wouldn’t look back and say, I wish I’d spent that time working instead.”

Her dedication paid off, in a series of photographs that show two people confronting death with integrity, grit and even humor. “They were dying, and I see them in their weak moments, but I see them in their alive moments and their strength,” Borowick said. “It’s strange, but there was a lot of beauty. This was a beautiful time.”

Her dedication paid off, in a series of photographs that show two people confronting death with integrity, grit and even humor. “They were dying, and I see them in their weak moments, but I see them in their alive moments and their strength,” Borowick said. “It’s strange, but there was a lot of beauty. This was a beautiful time.”

Witness, for example, the moment in which a newly-diagnosed Howie puts his hand on his wife’s butt as they’re walking into a Florida pool. “That was so him,” Borowick said. “He knew it would annoy her just a little.” The two also goofed around on the day Howie shaved Laurel’s head, with Laurel making herself Groucho eyebrows from cut-off bits of hair. “I think we needed that release,” Borowick said. “I remember thinking, how can I be paralyzed by this when they’re the ones going through it and they’re finding the joy and the lightness.”

From The Family Imprint, photograph by Nancy Borowick

At times, Borowick said, she began to overthink the project and “get into my own head too much.” There was the day she asked her parents if she could take a formal portrait showing their chemotherapy ports, thinking that the matching ports were “like wedding rings.” When her parents stripped off and said, “Let’s do this,” she was thrown off guard: the resulting image is so-so. But a moment later, when her father swooped in and gave her mom a hug, she captured a spontaneous moment that has become one of the project’s most enduring images. “They’re together, two becoming one, and there’s this sense of calm and peace in my dad’s expression which has always brought me comfort,” she said.

Nancy Borowick stands by her image of her parents hugging. Photograph by Sarah Coleman

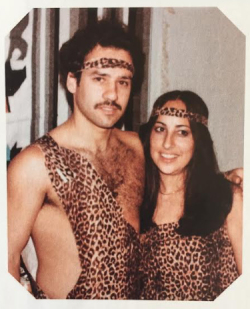

Throughout the exhibition, Borowick’s raw black-and-white photographs are interspersed with notes, lists, and colorful family snapshots from her childhood. “My parents did the decades well,” she said, waving at a shot of the couple in matching leopardskin loincloths and headbands. A charismatic trial lawyer who enjoyed a party, Howie was thrilled to be alive when his daughter got married in 2013. Naturally, Borowick shot part of the wedding—even climbing a tree to set up one image. “The first compliment everyone paid me was not, You look so beautiful, but, Your parents look amazing!” she said. “And that felt good, that’s what I cared about.”

Of course, her parents’ stories were not headed for a fairytale ending. As they approached their final days, Borowick was rigorous in her documentation. Her father died first, and—as she’d done at her wedding—Borowick went into the funeral hall early to set up a shot. “I still don’t know how I went in ahead of time to plan this picture,” she said. “But a lot of the things you do at these times aren’t rational. And photography often isn’t rational either—it’s just feeling.”

Of course, her parents’ stories were not headed for a fairytale ending. As they approached their final days, Borowick was rigorous in her documentation. Her father died first, and—as she’d done at her wedding—Borowick went into the funeral hall early to set up a shot. “I still don’t know how I went in ahead of time to plan this picture,” she said. “But a lot of the things you do at these times aren’t rational. And photography often isn’t rational either—it’s just feeling.”

A year later her mom was dying, and—knowing Laurel’s love for animals—Borowick found herself hatching plans to borrow puppies and ponies to bring to the house. Fellow photojournalist Stephanie Sinclair lent her dog, Moses, and there’s a wonderful shot of him sitting on Laurel’s chest. “At this point she didn’t really want to be touched, but she didn’t mind Moses sitting on her and snorting,” Borowick said. “He brought the levity that we needed.”

Nancy Borowick by her image of Moses on her mom’s chest. Photograph by Sarah Coleman

As she led the tour of her work, Borowick emanated the same sense of warmth that permeates her pictures. The love between her and her parents comes across clearly, as do Howie and Laurel’s individual and whimsical personalities—Howie the patriarch who could also be “a bit of a whiney baby”; Laurel the pillar of strength who, if occasion demanded, could rock a pink neon wig.

From The Family Imprint , photograph by Nancy Borowick

Howie and Laurel lived to see Borowick’s images of them published in the New York Times, and to witness the impact their story had on others. “I think that validated their experience in many ways, and gave a greater purpose and meaning to their lives,” Borowick said. Now, with both parents gone, she feels satisfied in the way she got to know them deeply through her images, and can hold on to them that way. “I learned a lot about my parents,” she said. “I only got thirty years with them. But I got really lucky.”

The Family Imprint will be on display in DUMBO, Brooklyn, through October 30. For information and directions, click here .

Visit Nancy Borowick’s website .

Buy The Family Imprint here .

4 comments on “ Life in the Face of Death: A Tour with Nancy Borowick ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Great story. Thank you.

What an interesting and touching piece

Brilliant work Sarah

Thanks for bringing this to us Sarah. I’ve seen this work as well but missed her talk at Photoville. It’s good to have your insight into Borowick’s experience.

It helps to have such open, loving, resilient parents to inspire and embrace your work. If only we could all do this for each other. Amazing.