Past Due: An Interview with Kerry Mansfield

Most of us have a few of them knocking around: those old, worn books that we can’t let go of, despite knowing we’ll never read them again. Maybe your college boyfriend handed you this one with a grave explanation of how it rocked his world. Maybe you stayed up all night to read that one, and the last pages are crinkly from where your tears plopped down and soaked the paper. Another might be a library book that never made it back to the stacks, despite your best intentions.

Most of us have a few of them knocking around: those old, worn books that we can’t let go of, despite knowing we’ll never read them again. Maybe your college boyfriend handed you this one with a grave explanation of how it rocked his world. Maybe you stayed up all night to read that one, and the last pages are crinkly from where your tears plopped down and soaked the paper. Another might be a library book that never made it back to the stacks, despite your best intentions.

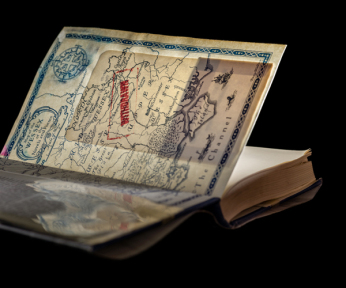

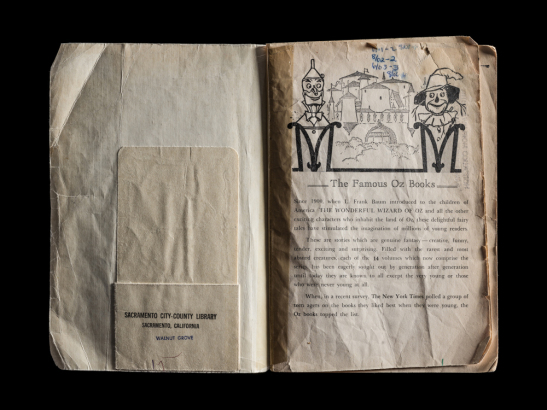

The tactile experience of books, and the nostalgic ties we harbor for them, is central to Kerry Mansfield’s Expired , a celebration of that most modest of literary tomes, the expired library book. Withdrawn from public libraries due to their damaged condition, these books are testaments to the love of reading. Now they exist in a netherworld, waiting for a kind hand like Mansfield’s to save them from the pulper.

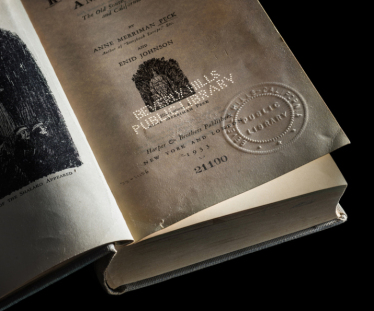

Set against black and photographed as if they are precious artifacts, the battered books seen here whisper to us of the past. (Most are beloved books from childhood, from The Wizard of Oz to Robinson Crusoe .) They have been touched by many, many hands. Some carry stern messages—like the warning we see in the front of a battered copy of Steinbeck’s Cannery Row (ironic here) that “All injuries to books beyond reasonable wear and tear and all losses shall be made good to the satisfaction of the Librarian.”

Mansfield’s work has long combined a sense of wonder and wistfulness with close, detailed scrutiny. Previously she has photographed

falling birds’ feathers

,

humans’ encounters with nature

, and

her journey with breast cancer

. Expired

is her ode to the beauty of loving an object into obsolescence, and—as in the Japanese art of wabi-sabi—accepting the natural cycle of growth, decay and death. .

Mansfield’s work has long combined a sense of wonder and wistfulness with close, detailed scrutiny. Previously she has photographed

falling birds’ feathers

,

humans’ encounters with nature

, and

her journey with breast cancer

. Expired

is her ode to the beauty of loving an object into obsolescence, and—as in the Japanese art of wabi-sabi—accepting the natural cycle of growth, decay and death. .

She sat down recently to talk to The Literate Lens.

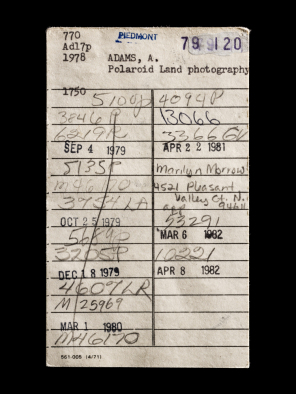

How did this project start? What was the first book you photographed?

The first book was Old Yeller , but the project started almost 3 years before that, when I found an old checkout card in the back of a book at Goodwill, and it took me back to being in the library as a child, back when there were checkout cards in books. I started looking for more cards, but in California they’d been replaced with digital scans long before. Then my partner found a copy of Old Yeller , ironically on eBay. It had the checkout card and battered pages, and it became a touchstone for the whole series.

Have you always been attracted to things that are worn and dinged-up?

Yes, but I have a double-sided personality. One side is hyper-organized and minimalist, and the other side loves the look and smell of old things. I grew up among antiques in a 110-year-old house with a single mother, so there were a lot of hand-me-downs. My grandfather was a captain in the Navy, he’d been stationed in Japan, and my grandparents had these amazing old paper lamps and pieces made from blue china. They were from a place I’d never been to, and you could see the wear and tear on them. I was intrigued by the idea that they’d been touched and used by people faraway.

What appeals to you about de-acquisitioned library books?

The way they’ve been loved so much. It’s different from a thing that’s just left to fall apart in a corner. The more battered and abused they are, the more valuable they are to me, which is the polar opposite of everything else in my life. To be a healthy person you have to allow for mess, for entropy. This project pays homage to that.

One of the things I loved about this work is the way the books have been presented so simply, but lit and shot to capture every tiny detail. How did you do that? For example, in the image that opens the book, of a novel open to the title page, where the page is lit from below so that light shines through a stamp?

One of the things I loved about this work is the way the books have been presented so simply, but lit and shot to capture every tiny detail. How did you do that? For example, in the image that opens the book, of a novel open to the title page, where the page is lit from below so that light shines through a stamp?

I’ve always been interested in police evidentiary photography, so I wanted to present the books in that way. But I also wanted viewers to feel they could almost touch the paper and feel its fibers. To achieve that, I dropped the light as low as humanly possible and made it rake across the book, as if it was a sun setting. I agree with one of my photographer friends who says that although most photographers throw a bunch of lights on their subjects, almost everything can be lit with a single light. In the case of that open book, there was also a very tiny light under the page. It took some work to get it right, obviously.

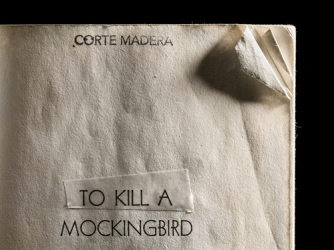

You have an image of the title page of

To Kill a Mockingbird

, where it looks like there’s some clear tape over the words ‘To Kill a.’

You have an image of the title page of

To Kill a Mockingbird

, where it looks like there’s some clear tape over the words ‘To Kill a.’

Yes, I found it exactly that way. My best guess is that a checkout slip was taped there, and when they withdrew the book they sliced it off, leaving the top of the tape. I thought there was something nice about the mystery of it. More often than not, these library books were discarded with love. Whoever has tended that book in the library has cared for it. There are some amusing things, like in the book called All About Dinosaurs , where the withdrawal notice has been stamped on a dinosaur’s butt. I don’t believe that’s accidental! Even when they’re being discarded, these books are being lovingly discarded.

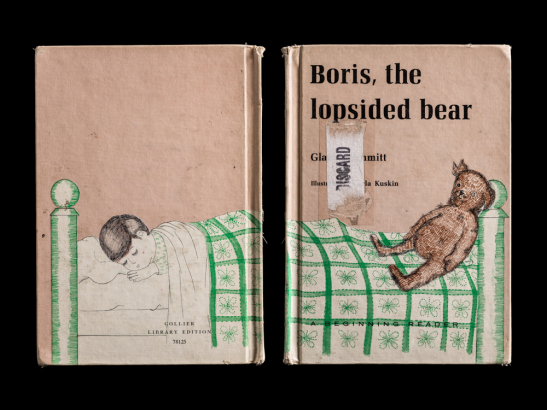

Another image I loved was of a book called Boris the Lopsided Bear . There’s such pathos in it, because it’s a book that’s already about a battered object, and the book itself is battered. Is there a story about that one?

There is! Typically, I’d shoot the front cover of the book, then the back cover, then composite the images to show both covers. In the composites, I’d always put the front cover on the left and the back cover on the right. But when I put the two Boris covers together, I realized they joined up and made a picture of Boris and his boy. So this is the only picture of covers where the back is on the left and front is on the right—and then it becomes even more tragic! There’s also a sad little ‘discard’ sticker coming half-off. It’s one of my favorite cover shots because I discovered something about it while making it. Also, I read the book as a child.

In the last few years, I’ve noticed a mini-trend of artists cutting up books or gluing them together to make art—do you have any feelings about that?

I think that if that’s how you’re manifesting your creativity, more power to you—as long as there’s an appreciation for the object. The polar opposite of that would be the Google Books warehouse where they tear books apart, scan the pages as quickly as possible, then pulp the remains. From a technical standpoint it’s brilliant, we’re moving forward, and on the other hand it’s gut-wrenching to think of all those books destroyed.

What happens to

your

books after you shoot them? Do you hang on to them?

What happens to

your

books after you shoot them? Do you hang on to them?

So far, yes. I’m lucky in that I live in a converted industrial space, and we have room for them. Being able to keep them is a luxury. Maybe it’s the latent librarian in me, but I feel like I’m the home of wayward library books. If I put them back in the system, I would feel like I was taking them back to the orphanage! I have 175 books stored in bins, and another 4 bins that I have yet to shoot.

This project has had a great critical reception. How have general readers reacted to it?

It’s been wonderful. One really fascinating thing is that people have started coming to me with books, or sending me books in the mail. Most of them are not ex-library books, so I have to say no. But I’ve been exposed to a lot of people whose books are precious to them. People really have a strong desire to share the books they treasure.

It sounds as if you’re not going to draw a line under Expired any time soon.

I thought I’d done it, but books keep finding their way to me. My partner is a complete enabler. When I’m going through a hard time, he’ll buy me books to cheer me up. I’m very picky now because I’ve seen so many patterns of damage, and I want to find different ones or new, exciting books. Right now I have in my possession a 1929-32 U.S. Negro Census. It documents how many African-American lawyers there were in Wyoming, how many doctors in California, et cetera, and it says it was written and compiled by Negro clerks. I mean, this is a piece of history! I can’t believe it’s not in a museum! This needs to be photographed! [laughs] I don’t have a choice, right?

all images (c) Kerry Mansfield

Kerry Mansfield will be giving an artist talk and signing books at 7 p.m. on October 25 at The Last Bookstore in Los Angeles. For details click here .

Visit the artist’s website here .

2 comments on “ Past Due: An Interview with Kerry Mansfield ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Enjoyable reading.

An excellent and thoughtful article. Thank you.