Too Young To Wed: The Tragedy of Child Marriage

How many children in the world would you guess are currently married, and how young is the youngest? The idea of child marriage seems archaic: it brings with it echoes of medieval times, or of royal alliances where securing an early marriage led to consolidation of property and power. Chances are that when we hear the term today, most of us don’t imagine a five-year-old in contemporary rural India who—despite a national law against it—is getting married to a man eight times her age.

How many children in the world would you guess are currently married, and how young is the youngest? The idea of child marriage seems archaic: it brings with it echoes of medieval times, or of royal alliances where securing an early marriage led to consolidation of property and power. Chances are that when we hear the term today, most of us don’t imagine a five-year-old in contemporary rural India who—despite a national law against it—is getting married to a man eight times her age.

Rajni, 5, is seen after having just woken up before her wedding ceremony in Rajasthan, India on April 28, 2009. (c) Stephanie Sinclair/Too Young to Wed

Evidence suggests that we should, though. Today, child marriage is prevalent across the developing world, a reality in more than fifty countries. It can involve girls as young as five and six, and although some communities try to prohibit sex until the wife is older, this edict is very often ignored. An underage girl is married somewhere in the world every two seconds, and the United Nations Population Fund (UNPFA) estimates that over the next decade, there could be another 142 million child brides.

Photojournalist Stephanie Sinclair first came across the issue in 2002, when she was assigned to cover women’s self-immolation in Afghanistan. In a burn unit in the city of Herat, she discovered a disturbing pattern: many of the women and girls who’d set themselves on fire had been forced into marriage as children.

Appalled, Sinclair decided to take on the issue of child marriage as a long-term project. This meant treading gently and investing time, because communities are often secretive about the practice. “There’s no way the work could have been done without people in each community who wanted to support what we were doing,” she says. “They agreed the practice was hurting the community, and they wanted to tell the world so that it could end.”

A seasoned photojournalist, Sinclair was well placed to do this work. A former staff photographer with the Chicago Tribune , she had been part of a team that won a 2000 Pulitzer Prize for reporting on problems in the airline industry. Another story she did for the Tribune , on failures in the capital punishment system, led the governor of Illinois to put a moratorium on the death penalty in the state—which, says Sinclair, was a lesson in the power of journalism. “That was a big deal, early in my career.”

Another big deal was being sent to pre-war Iraq to cover the lead-up to war, then staying during the invasion, refusing to be embedded with the military because she wanted to tell stories of ordinary Iraqis. Sinclair fell in love with the region and its people: she ended up leaving the Tribune and living in the Middle East for six years, during which time she did stories for Time , the New York Times Magazine and National Geographic .

Faiz, 40, and Ghulam, 11, sit in her home just before their wedding in rural Afghanistan, Sept. 11, 2005. (c) Stephanie Sinclair/Too Young to Wed

Like other issues she’d covered, child marriage was nuanced and challenging. In some developing world countries—especially where conflict or natural disaster has raged—parents see child marriage as a way of protecting their daughters. In such places, a girl’s value often rests on her “pure” body, meaning that a girl who is raped or has premarital sex is considered worthless. So parents might be caught between a rock and a hard place, with child marriage considered the better option.

Because of this, Sinclair often finds herself walking an ethical tightrope. “I’ll absolutely never say it’s okay to have sex with children—that’s not a question,” she says. “But I’ll often try to be somewhat protective of the communities, because there are many parts of their traditions that are beautiful and should be celebrated. It’s just about taking the harmful part out.”

At 14, Sulmi in Guatemala is nine months pregnant with a girl. “My family was a little sad when I got married.” (c) Stephanie Sinclair/Too Young to Wed

Speaking of beauty, Sinclair uses it in her photographs as a way of drawing people in. Tribal dress and stunning landscapes can make an image dramatic, though her focus is always on the emotional connection between subject and viewer. “I’ve always approached this project with the idea that this person could be me, or someone I love,” she says. “I won the birth lottery. These girls didn’t, and I feel it’s my obligation to fight for them, because there were people who fought for us.”

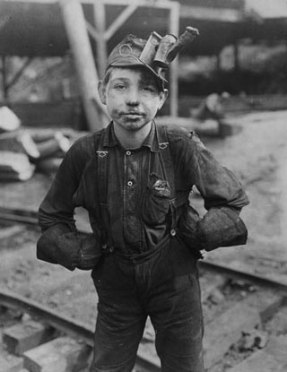

In this case, fighting means creating a body of incontrovertible visual evidence. A hundred years ago, photographer Lewis Hine did something similar, confronting a complacent American public with proof that child labor existed in every state. Sinclair was chasing a similar goal, but on an international level. “Before these pictures existed, most people assumed child marriage was abolished a long time ago. That’s why I photographed so many weddings—because I wanted to say, over and over, country by country, that this is still happening.”

Now, thirteen years since she started, there’s a lot to celebrate. Sinclair has partnered with the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), Equality Now, the Population Council, Samburu Girls Foundation, and several governments. “There were plenty of organizations that knew about the importance of this issue, but the photographs kind of catalyzed the whole conversation,” she says. “It made them imagine their daughters or their sisters in the picture.”

Young girls in Yemen, where child marriage is rampant. This image is in the Too Young to Wed print sale (details below). (c) Stephanie Sinclair/Too Young to Wed

In 2012, Sinclair also created her own nonprofit organization, Too Young to Wed , which advocates for an end to child marriage and provides support to girls in communities where the photographs were made. For example, TYTW is working with a grassroots organization in Samburu, Kenya that supports rescued girls from child marriages and then works with parents to allow them to attend boarding school instead. “We don’t want to just take pictures and walk away,” Sinclair says. “In the course of this project, I’ve never done that.”

To bring the work new attention, Sinclair will be exhibiting her photographs this year in one of the shipping containers that make up the Brooklyn pop-up photo village Photoville , which opens today. In conjunction with Photoville, which runs from Sept. 10-20 , TYTW will host its first print sale – offering the opportunity to purchase a signed, archival 8×10 inch print for $100. Sinclair says that one hundred percent of the contributions received will directly support TYTW’s mission to protect girls’ rights and end child marriage. If you can’t make it to Photoville, prints are available from the TYTW website .

At 10, Nujood fled her older, abusive husband and challenged the marriage in court. She is now back with her parents and attending school. (c) Stepanie Sinclair/Too Young to Wed

In the long term, Sinclair says, the goal is to chip away at the perception of girls as sexual chattel. “If girls were valued for other things—for their intellect, or for what they could bring to the society on other levels, then they wouldn’t lose their value if they were raped or had sex before marriage. They should have value outside of their bodies.”

But until that goal is met, she’ll continue fighting, advocating, and deriving satisfaction from the relationships and images she makes. “When you share someone’s story, you’re validating their experience as being very difficult, and agreeing this shouldn’t have happened to them,” she says. “As difficult and dangerous as that can be, it’s also incredibly rewarding.”

———————————————————————————-

Support

Too Young to Wed

by making a donation or buying a print for $100 during the print sale, September 10-20, 2015. Proceeds will benefit the Samburu Girls Foundation in Kenya, the women and children of the Kagati Village in Nepal, and girls in the village of Gombat, outside Bahir Dahar in Ethiopia. For more information and to purchase a print, click on the button to the right.

Support

Too Young to Wed

by making a donation or buying a print for $100 during the print sale, September 10-20, 2015. Proceeds will benefit the Samburu Girls Foundation in Kenya, the women and children of the Kagati Village in Nepal, and girls in the village of Gombat, outside Bahir Dahar in Ethiopia. For more information and to purchase a print, click on the button to the right.

The 4th annual Photoville runs from September 10-20 on the Brooklyn waterfront. For hours, directions and programming, click here .

Stephanie Sinclair will be participating in a panel discussion at Photoville, Influencing Policy and Social Change Through Photography , on Saturday September 12th from 4:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. Click here for details.

Sinclair will also be one of the featured speakers at An Evening with National Geographic on Friday, September 19th in the Photoville beer garden. Other speakers are Katie Orlinsky, Robert Clark and David Guttenfelder. For more information click here .

9 comments on “ Too Young To Wed: The Tragedy of Child Marriage ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Man, sometimes this world is just too crazy to understand. As a new father to a newborn girl…it just blows my mind that this sort of thing happens. I mean, I always KNEW stuff like this happens as I always try to keep an open eye/mind to the world, but man does it hit close to home sometimes. I couldn’t imagine giving up my daughter at 5…insanity…

Thank you for sharing this important project. Christiane Monarchi, London

Christiane Monarchi Editor, Photomonitor (www.photomonitor.co.uk)

Sarah, This is such a hard topic to photograph and write about, but awareness and change are definitely needed. I hope Sinclair’s work helps these children.

Reblogged this on Tori's Target and commented:

There are many causes we can fight for with veganism being one of them. Its crucial to remember that many people need our help. I’ve never been as enlightened in my life as I have this summer. I have read books and increased my awareness of the issues plaguing society. Sometimes it’s necessary to branch and see the things that other refuse to. I challenge you all to leave your comfort zones and learn about the struggles our brothers and sisters are facing.

Reblogged this on 政治 and commented:

いい記事です。

Sarah! This blog is incredibly powerful. Thank you. Hard to believe how un-evolved humans are…

😊 otima materia

I think the debate on child marriage is a bit more complex than that. It revolves around a ever-existing tension between consent and ethnocentrism. Consent, in most cultures, is required for marriage, and the age of consent is usually concentric with voting age. It’s not easy to tell if we should have the same age requirement for both voting and marrying, especially when we appreciate that age of consent for sexual relationships is reached earlier.

Second, what level of consent should be required for marriage. Should both the partners have equal capacity to consent in a relationship? That both should have is a purely western conception, and to say that the only fair way to go is to go Western is a bit ethnocentric. Why should one attach the same value to consent as western cultures do? When it comes to assigning values, it’s almost impossible to logically defend your answers.

By the way, some western states countenance chastisement of children during their upbringing. If the children could be beaten when they don’t fall in line, why can’t they be told to live with somebody of their parents’ choice, which will surely have a vast amount of first-hand experience of life and its harsh realities than a 22 year old would have? Why allow children be beaten and not have them choose a life which their parents’ experience suggests would be in their best interest?

Also, in most societies where child marriage takes place, the writ of state is almost non-existent. The powerful rob, rape and kill with impunity, and marrying young girls often becomes more of securing them with someone than exposing them to a lawless, patriarchal society ruled by all the base instincts of man. Education, upward social mobility and justice is usually non-existent in such societies. Should we then fight against child-marriage before we fight against the dynamics of their corrupt system? Should we kill our horses before we have invented our car?

Personally, I strongly believe that child marriage is unethical, and even, criminal, but also, I believe, there’s a need to understand the pillars supporting that institution. Just cursing the darkness won’t do. Maybe we should try to understand what sustains darkness even in this age of light, modernity & advancement and have it busted bad

http://bustedbad.com/

It’s crazy how people think that child marriage is ok. I guess I just don’t understand the point of the parents. Thank you for sharing! This is a really nice article!