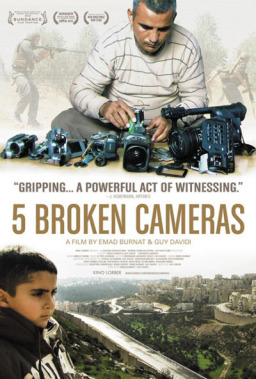

Five Broken Cameras

How do you make people actually get interested in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict? At this point, the whole thing seems so intractable, the lines in the sand so deeply dug, that casual observers have little motivation to get involved. We’re like serial daters whose hopes have been dashed too many times; at this point, we’d rather just sit home and eat nachos than have the peace process limp into our lives.

How do you make people actually get interested in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict? At this point, the whole thing seems so intractable, the lines in the sand so deeply dug, that casual observers have little motivation to get involved. We’re like serial daters whose hopes have been dashed too many times; at this point, we’d rather just sit home and eat nachos than have the peace process limp into our lives.

I did find myself caring, though, at a screening of the documentary Five Broken Cameras on Sunday night. I should say from the outset that this post isn’t exactly about photography, art or literature, but since the film combines documentary advocacy with personal storytelling and artistry, I feel I can stretch a point. There have been some great photography projects about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, including Gillian Laub’s Testimony and this intriguing project by Swiss photographer Olivier Suter. In this case, film proved to be the most powerful way to tell the story.

The movie follows Emad Burnat, a Palestinian farmer in Bil’in, a village on the West Bank. Referring to himself as a simple falah , or peasant, Emad starts out simply wanting a decent life for his family. But when he’s given a video camera to document the birth of his fourth son Gibreel, something changes.

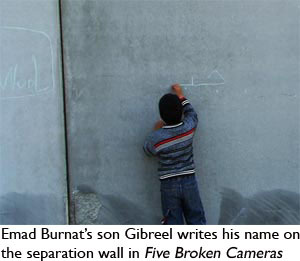

Gibreel’s birth happens to coincide with the expansion of Jewish settlements near Bil’in. Soon, Israel sanctions a “separation fence” to be built through the surrounding farmland, and the people of Bil’in watch helplessly as their land is annexed. The villagers decide to mount a nonviolent resistance, and as they head out onto the streets, Emad runs after with his camera.

Gibreel’s birth happens to coincide with the expansion of Jewish settlements near Bil’in. Soon, Israel sanctions a “separation fence” to be built through the surrounding farmland, and the people of Bil’in watch helplessly as their land is annexed. The villagers decide to mount a nonviolent resistance, and as they head out onto the streets, Emad runs after with his camera.

What follows is a story that illuminates the larger conflict while also being deeply personal. As the protests in the village intensify, Emad finds himself becoming an unlikely activist—then being targeted as one camera after another is broken. The first is hit by a gas grenade thrown by Israeli soldiers; the second is shot at during a protest against Israel’s 2006 invasion of Lebanon. The third stops working when a sniper’s bullet lodges in it. And so it goes on.

Emad also uses his young sons to track the progress (or lack thereof) of the peace process. His first son was born in a period of hope, just after the Oslo Accords; his second son came into the world during the Intifada. Now comes Gibreel, whose early life is marked by fences and barbed wire. When Gibreel begins to talk, his first words—tellingly—are “army,” “wall” and “cartridge.”

As the danger increases, Emad has to ask himself some hard questions about what he’s doing, especially when his wife begs him to “stop filming and spend time with your family.” But by that time he’s hooked, too deeply involved to stop. When his friend, the gentle and optimistic Phil, is killed in one of the protests, it only strengthens his resolve.

Five Broken Cameras is an Israeli-Palestinian collaboration. It was made by Burnat and Guy Davidi, a left-wing Israeli video activist who spent time in Bil’in during the protests. No film about the Israel-Palestinian conflict could be neutral, and this one doesn’t pretend to be. Israelis exist here only as stone-faced soldiers, grimly doing the state’s bidding, while the Palestinians are presented as uniformly noble and heroic. The film doesn’t represent the fact that many prominent Israelis joined the Bil’in protests.

But the Palestinians shown here are so appealing, so optimistic and creative in their protests, that it’s impossible not to feel outraged on their behalf—especially when the Israelis subject them to brutal force. In one particularly shocking scene, a protester is taken aside by Israeli soldiers and calmly shot in the leg, just to teach him a lesson. Faced with that kind of provocation, the Palestinians’ nonviolence does indeed seem noble—and fragile. “I think about the children, like Gibreel,” Emad says. “How will they be able to bear their anger?”

But the Palestinians shown here are so appealing, so optimistic and creative in their protests, that it’s impossible not to feel outraged on their behalf—especially when the Israelis subject them to brutal force. In one particularly shocking scene, a protester is taken aside by Israeli soldiers and calmly shot in the leg, just to teach him a lesson. Faced with that kind of provocation, the Palestinians’ nonviolence does indeed seem noble—and fragile. “I think about the children, like Gibreel,” Emad says. “How will they be able to bear their anger?”

The fact that the film was made by a Palestinian and an Israeli might seem to offer a flicker of hope, but it’s modest. In a Q&A after the screening, Davidi confessed that left-wing activists like him are “seen as traitors” by many Israelis. Whereas a few years ago, the death of an Israeli activist at a pro-Palestinian protest was big news, “I think the Israeli public is ready for an Israeli activist to be killed by a soldier and not make a fuss about it,” he said. (Click here to see a Q&A with Burnat and Davidi at the Film Society of Lincoln Center.)

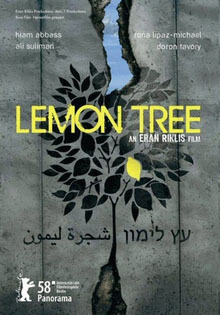

For those of us outside Israel, the documentary approach—with its irrefutable visual evidence—is undeniably powerful. A few years ago I saw the Israeli feature film

Lemon Tree

, a fictionalized account of a similar land dispute. The film imagined a slightly far-fetched scenario in which the Israeli defense minister moves to the border of the West Bank, and his wife befriends a Palestinian woman whose neighboring lemon groves are threatened with destruction. It was well-acted, but the story was too tidy and schematic to be really powerful. Even the great Palestinian actress Hiam Abbas couldn’t save it.

For those of us outside Israel, the documentary approach—with its irrefutable visual evidence—is undeniably powerful. A few years ago I saw the Israeli feature film

Lemon Tree

, a fictionalized account of a similar land dispute. The film imagined a slightly far-fetched scenario in which the Israeli defense minister moves to the border of the West Bank, and his wife befriends a Palestinian woman whose neighboring lemon groves are threatened with destruction. It was well-acted, but the story was too tidy and schematic to be really powerful. Even the great Palestinian actress Hiam Abbas couldn’t save it.

Five Broken Cameras is a crafted film too: Davidi and Burnat have given it a clear structure, with a chapter for each broken camera. There are lyrical grace notes, with poetic shots of nature that contrast vividly with the footage of tear-gassed protesters. Everything is tied together by Emad’s quiet, thoughtful voiceover narration, where he wrestles out loud with his newfound responsibility. “I have to believe that capturing these images will have some meaning,” he says.

But although there’s artistry in the film’s construction, the documentary aspect anchors it, giving it heft and gravity. Emad is a thorough documentarian, and the evidence he captures here is startling and incriminating, from his friend’s unnecessary death to settlers firebombing Palestinian olive groves. Added to this, the film gives profound insight into the life of one ordinary Palestinian family, and a community—and this, perhaps, is its most powerful advocacy weapon. It’s a tender portrait that puts a human face on an inhuman conflict.

——————————————————————————————————-

Five Broken Cameras is screening this week at Film Forum. To see showtimes click here .

Further screenings are happening in Boston, San Francisco, Albuquerque, Santa Fe, Berkeley, Lake Worth, Washington D.C. To see the full schedule, click here .

2 comments on “ Five Broken Cameras ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Thank you for yet another insightful and intelligently articulated post. I look forward to the next one.

So interesting!

It is so important to have the human aspects of the intractable conflicts presented. Pairing this film with the critical geography & mapping work by Eyal Weizman of the Israeli settlements on the West Bank would be interesting. See, for example, his book “Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation”

http://www.amazon.com/Hollow-Land-Israels-Architecture-Occupation/dp/1844671259