Making War Personal

In the past ten years, photojournalist

Kate Brooks

has been in almost every conflict zone in the Greater Middle East. The second intifada in Israel?

Check.

Cairo’s Tahrir Square during the revolutionary demonstrations?

Check.

The mountains of Tora Bora in Afghanistan, while the U.S. army was trying to flush out Bin Laden?

Check, check and check again.

In the past ten years, photojournalist

Kate Brooks

has been in almost every conflict zone in the Greater Middle East. The second intifada in Israel?

Check.

Cairo’s Tahrir Square during the revolutionary demonstrations?

Check.

The mountains of Tora Bora in Afghanistan, while the U.S. army was trying to flush out Bin Laden?

Check, check and check again.

At thirty-four, Kate is already a seasoned veteran of the field, with a body of work that has been published in Time , Newsweek , The New Yorker , The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times . “Intrepid” is an obvious word that comes to mind when describing her, though she insists that the amount of time she puts herself at risk is relatively small. But there’s nothing small about her pictures, which are gutsy and expressive, and often have the gravity of an Old Master painting. They deconstruct war, turning it from an abstract concept into something that affects individuals and families.

I recently had the pleasure of interviewing Kate for an article that will appear in the fall issue of

PDN Edu

. She has an amazing new book out called

In the Light of Darkness

, which documents her ten-year odyssey through a war-torn region. In the book, Kate intersperses her images in with a series of chapters in which she tells her own story. The combination is highly effective, drawing the reader into her world, illuminating the stories behind the images and the dangerous situations she encountered. The photographs are often

chiaroscuro

, dramatic compositions of light and dark that underscore the book’s message of hope amid destruction.

I recently had the pleasure of interviewing Kate for an article that will appear in the fall issue of

PDN Edu

. She has an amazing new book out called

In the Light of Darkness

, which documents her ten-year odyssey through a war-torn region. In the book, Kate intersperses her images in with a series of chapters in which she tells her own story. The combination is highly effective, drawing the reader into her world, illuminating the stories behind the images and the dangerous situations she encountered. The photographs are often

chiaroscuro

, dramatic compositions of light and dark that underscore the book’s message of hope amid destruction.

When I caught up with Kate, it was midnight in her home base of Beirut and she was leaving the next day for Syria, where the United Nations had just suspended its missions due to escalating violence. Graciously insisting that she had just had an espresso and wasn’t tired, Kate took time out to talk about the risks and rewards of her work.

LL: Your book is a really interesting mixture of text and images. It has more narrative text and is more personal than the average photography book. Why did you decide to do it that way?

KB: The text draws people who wouldn’t typically buy a book of war photography. For me, in many ways, those people are the most interesting audience.

LL: How so?

KB: Well, I think photographers are often the primary consumers of photography books. If you do a book that’s appreciated by that milieu, it’s wonderful because they’re the toughest critics. Ultimately though my work has been about making people try to understand what war is like; trying to convey an experience most readers will never have and to make them reflect. So to have people who aren’t journalists or photographers buy the book and be moved by the pictures feels like a major accomplishment to me.

LL: Definitely! I agree that the text makes the book really accessible and enhances the pictures, as well as counterbalancing some of the more disturbing imagery. Was it hard to achieve that combination?

KB: Structuring the book was challenging because I wanted it to be personal but not too personal, and I didn’t want my personal story to eclipse or detract from the pictures. Finding a balance was hard, a lot of text had to be cut because it wasn’t a full memoir, but I think I managed.

LL: I was struck by how artistic the images were, even when you were shooting very disturbing subject matter. (I’m thinking, for example, of the image on pages 102-3, of a man outside the Tomb of Imam Ali in Najaf just after a car bombing.) Is it hard to focus on composition, etc., at such times?

KB: I just shoot. Taking the aftermath of the bombing at the Tomb of Imam Ali as an example, I was totally absorbed in the immediacy of the moment. People were trying to attack me and the scene was horrific. I was overwhelmed by everything that was happening at once and I had to keep moving every 15 seconds. In those types of situations I go into autopilot mode.

LL: War photography is known to be one of the most stressful and risky occupations out there. How do you account for the fact that you’ve managed to stay safe?

KB: While I’ve shown a real commitment to working in this region, the amount of time I put myself at real risk is relatively small in relation to the time I spend here. I often get called a war photographer, which is a title I’m reluctant to accept, partially because I’ve always been more interested in the periphery of combat, in how ordinary civilians survive and manage and partially because I recognise that there are a lot of people who are braver than I am. All of that said, I’ve had a lot of close calls. I’ve been very lucky.

LL: What about the psychological effects of what you have to deal with?

KB: I’ve gone through periods of time where I’ve struggled with depression because of things I’ve witnessed or survived and faced sheer exhaustion. Before the 2006 war in Lebanon, I was traveling constantly and I’d wake up sometimes and have no idea where I was. For a few years I stopped doing long extended trips and limited my travel; it was time to slow down and focus more on myself. It’s not easy to find a balance, but I try in different ways.

LL: You’ve worked in many countries where women don’t enjoy as many freedoms as in the West. In Afghanistan, you were constantly told that it was no place for a woman to be. Is it hard to do your work under those circumstances?

KB: Well, you know, when I have men who say, you should get another job, I understand! They’re not saying I’m not capable, it’s just, why are you putting yourself in danger? But I don’t necessarily think it’s tougher for women to work. In the Middle East, it’s actually easier to be a female photographer because you can cross gender lines in a way men can’t.

LL: All the same, you write about some iffy encounters with men who tried to take advantage of you.

KB: Yes, but considering the amount of time I’ve been in the region and the situations I’ve been in, the sexual harassment I’ve experienced over the last eleven years doesn’t even count for one percent of my time. I was recently on a panel discussion about women and safety in the field, and I said that for the two dozen times I’ve been sexually harassed over the past decade, probably a third of those times happened in the “west” and another third by colleagues or American or British soldiers. When it happens it’s uncomfortable of course, but to the extent to which I’ve exposed myself to danger or made myself vulnerable, it’s really relatively minor.

LL: We should also point out that for every man who harassed you, there were many more who befriended and protected you and became like family.

KB: That’s right. And at times complete strangers have even helped me.

LL: When you’re documenting suffering is it possible (or even desirable) to stay objective as a photojournalist? Do you feel your work is more a case of advocacy?

KB: I don’t believe that emotional objectivity exists when dealing with human rights atrocities and human suffering. But a photojournalist’s job is to tell the truth and present the facts. When it comes to human suffering and the human cost of war, I think there’s an emotional truth photographs can capture that transcends all of that and reminds the viewer of the cost of war – human lives, the breakdown of society and loss of culture. It’s incredible when photographs are a catalyst for tangible change or make a difference.

LL: Can you give an example of when that’s happened to you?

KB: During the Pakistan earthquake I was there in the first few days, and I took a picture of a little girl whose head wound was being operated on without anesthetic in a field hospital. The United States was in the process of mobilizing aid, and the image ran on the front page of The New York Times . It was one of those moments when I knew every single person in the U.S. involved with the issue would be seeing that heartwrenching picture on a day when critical decisions were being made.

LL: The book spans 10 years, from the war in Afghanistan to the Arab Spring. How does it feel to look back on that body of work and to know you witnessed so much history?

KB: I feel like I’m 34 going on 100!

LL: So what are your career goals for your next centennial?

KB: I’ll continue photographing the world as I see it, focusing on the stories I’m drawn to tell. Last year I worked as a cinematographer on a documentary called The Boxing Girls of Kabul, about the Afghan women’s national boxing team. It was a new medium for me and I enjoyed it tremendously. Depending on the project, I’d like to do more documentaries, maybe one a year.

LL: At the end of your book, you hint that you might have had enough of covering conflict (at least for a little while). And yet you’re heading off to Syria this week…

KB: Yes [laughs]. I texted my mom yesterday and told her, take a deep breath and don’t freak out, I’m going to Syria for a week. She said, you need to follow your heart and do what you feel drawn to do. I no longer have a curiosity about war, but I still feel passionately about covering human rights issues and I still care deeply about what is happening in the Middle East.

See more of Kate’s work on

her web site

.

4 comments on “ Making War Personal ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Wow, I just ordered this book. What a compelling interview. One of my favorite books by Arturo Perez-Reverte, The Painter of Battles, deals with the fallout and consequences of war photographs. This book, which is non-fiction, sounds absolutely fascinating. Thanks, Sarah, for bringing it to our attention.

Great interview. Thank you, Sarah, for bringing this extremely talented photojournalist to my attention. I look forward to adding her book to my collection.

Excellent interview and great insight into the issues that lie behind the images. Great post.

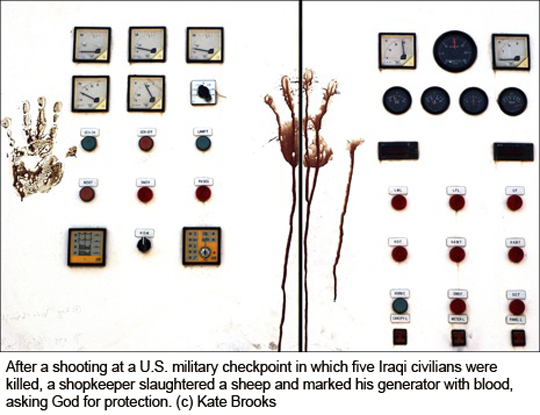

The subject is so powerful and direct in the hand/ generator image. Done without dogma. Instead, it gets inside the nature of the war the photographer witnesses. Regarding form and composition within the split-second: I told an artist recently that I liked the compositions in aerial paintings she had done from observation of fairly quick-changing subject matter. They were nonetheless clear but complex. Similar to Kate, she told me that when she works, she doesn’t think about composition.

Like the allusion to master paintings in this context. Thanks for a great interview and great introduction to this photojournalist.