Triangulated

On March 25, 1911, the United States experienced its deadliest ever industrial disaster. At around 4:40 p.m. that day, a fire broke out in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, on the top three floors of the ten-storey Asch Building east of New York’s Washington Square Park. What happened next is well known. Firemen arrived, but their ladders didn’t stretch above the sixth floor. Victims were trapped, interior doors having been locked to prevent factory girls from smuggling supplies out when the guard was off duty. Horrified passersby watched as, one after another, workers jumped to their deaths from high floors. In as little as twenty minutes, one hundred and forty-six people had died.

On March 25, 1911, the United States experienced its deadliest ever industrial disaster. At around 4:40 p.m. that day, a fire broke out in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, on the top three floors of the ten-storey Asch Building east of New York’s Washington Square Park. What happened next is well known. Firemen arrived, but their ladders didn’t stretch above the sixth floor. Victims were trapped, interior doors having been locked to prevent factory girls from smuggling supplies out when the guard was off duty. Horrified passersby watched as, one after another, workers jumped to their deaths from high floors. In as little as twenty minutes, one hundred and forty-six people had died.

Since then, the Triangle Fire has inspired many works of art. There have been films (the first one, from 1912, is below), plays, novels, documentaries–even rock songs. “Flames licked at their backs, their faces gripped with fear,” sings the group The Brandos in its 2006 song The Triangle Fire . “A last, shared glance and final embrace/They leaped to their tragic and senseless fate.” (For a list of the fire’s appearance in popular culture, click here .)

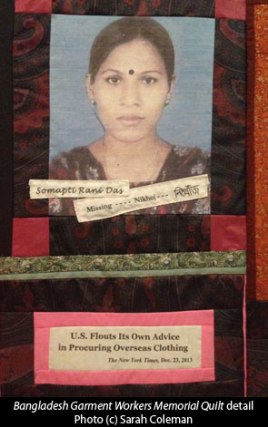

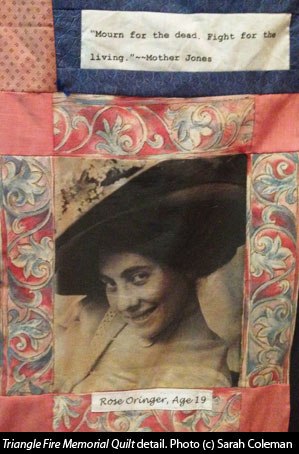

Recently, I went to the Cathedral of St. John the Divine to see another cultural artifact inspired by the fire, Across the Centuries, Across the Continents: Triangle Fire and Bangladesh Garment Workers Memorial Quilts . (Thanks to Elyse Singer for alerting me to this exhibit.) The creation of artist and activist Robin Berson, these two quilts incorporate photographs and texts transferred onto fabric and made into commemorative squares that have been stitched together into quilts. While one commemorates the Triangle Fire, the other memorializes a more recent news event–the terrible 2013 collapse of a garment factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and other similar disasters in that country.

Of course, memorial quilts have an illustrious history. The biggest and most famous one is the AIDS memorial quilt , begun in the 1980s and now boasting over 48,000 panels, but there are others, including this one commemorating 9/11 victims. A quick Google search also reveals instructions on how to make your own memorial quilt and showcases quilters offering to make one for you .

In the case of the Triangle and Bangladesh disasters, the motif of a quilt is especially appropriate. In both cases, these disasters happened in factories where low-wage workers were jammed into small, unsafe spaces to sew affordable garments. Most of these workers were female, and historically, quilts have been a craft in which women could express themselves artistically–without ruffling the feathers of fathers and husbands who would never have let them study art.

In the case of the Triangle and Bangladesh disasters, the motif of a quilt is especially appropriate. In both cases, these disasters happened in factories where low-wage workers were jammed into small, unsafe spaces to sew affordable garments. Most of these workers were female, and historically, quilts have been a craft in which women could express themselves artistically–without ruffling the feathers of fathers and husbands who would never have let them study art.

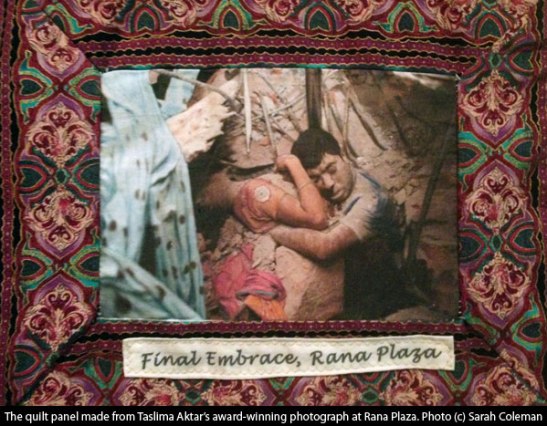

Hanging opposite each other in the intimate St. Boniface Chapel, the quilts are delicate and moving. In the Triangle quilt, Berson incorporates texts from activists and union leaders (the disaster led to the growth of the union movement and better safety standards). In the Bangladesh quilt, the texts are predominantly from newspaper articles with damning headlines (“U.S. Flouts Its Own Advice in Procuring Overseas Clothing”) but the photographs, being contemporary and in color, are more intense. One image, labeled ‘Final Embrace, Rana Plaza’ shows a World Press Photo award-winning photograph of a dead man and woman clinging together amid the rubble of the eight-storey Rana Plaza building in Dhaka, which collapsed in April, 2013, killing 1,129. (Read about the photo here ).

After seeing the quilts, I was curious to read Katherine Weber’s 2006 novel Triangle , which I remembered hearing about when it came out. Nominated for several literary prizes, the novel weaves a fictional story around a character based loosely on Rose Freedman, the oldest living survivor of the fire, who died in 2001 aged 107. It sounded promising.

Unfortunately,

Triangle

left me a bit perplexed. It starts out with a searingly direct and moving testimony from Esther Gottesfeld, the character based on Freedman, about what happened to her on the day of the fire. But then we get twenty pages about George Botkin, a hugely successful contemporary composer whose music is inspired by amino-acid and genome sequences. George, it turns out, is the boyfriend of Esther’s granddaughter Rebecca, and he’s a fascinating character—so fascinating, in fact, that I felt Weber was more interested in him than in her story about Esther. The dark mystery at the center of Esther’s story was so utterly predictable that I’d guessed it long before I was half way through.

Unfortunately,

Triangle

left me a bit perplexed. It starts out with a searingly direct and moving testimony from Esther Gottesfeld, the character based on Freedman, about what happened to her on the day of the fire. But then we get twenty pages about George Botkin, a hugely successful contemporary composer whose music is inspired by amino-acid and genome sequences. George, it turns out, is the boyfriend of Esther’s granddaughter Rebecca, and he’s a fascinating character—so fascinating, in fact, that I felt Weber was more interested in him than in her story about Esther. The dark mystery at the center of Esther’s story was so utterly predictable that I’d guessed it long before I was half way through.

In short, then, the book is uneven, and it only gets more so. The relationship between George and Rebecca is well drawn: their conversations are delightful and authentic, and the description of George’s symphony based on the Triangle Fire is as virtuosic as the symphony itself. If Weber had stuck to these elements, the novel would have been better. But she introduces a catalyzing character, a feminist academic called Ruth Zion, who suspects Esther’s secret and interviews her. To put it bluntly, Ruth is one of the worst drawn characters I have ever seen in fiction. Her stilted, awkward conversation makes her come across as a caricature on steroids, more fembot than human being. Take this example of her speech, from a phone conversation with Rebecca:

“I will take that as a rhetorical question, just as I will overlook your unfortunate use of vulgar language, because I recognize that you are becoming very emotional, regrettably, owing to your grief. I am still planning to include you in my acknowledgments.”

“I will take that as a rhetorical question, just as I will overlook your unfortunate use of vulgar language, because I recognize that you are becoming very emotional, regrettably, owing to your grief. I am still planning to include you in my acknowledgments.”

Has anyone in the universe ever spoken like that? I understand Weber wants to poke fun at Ruth as a super-earnest feminist, given to presenting papers with titles like Desire and Attire: The Shirtwaist Reconsidered at conferences of the Herstorical Society. But she goes way over the top, then some, making Ruth utterly ridiculous. In a novel about an event that prompted feminist activism that led to increased safety standards and union participation for female workers, it seems especially tone-deaf to include a character who makes feminism into a joke.

Triangle isn’t the only fictional treatment of the infamous fire. Not listed on the Wikipedia page I linked to above is Edward Rutherfurd’s 2009 novel New York . I remember learning a lot about the Triangle fire from that novel, so I took another look at it to refresh my memory.

Rutherfurd writes sweeping epics of novels with titles like

New York

and

Paris

. They convey the history of a place through characters who happen, very conveniently, to be well-placed for all major events in that place’s history. They are contrived, but enjoyable and extremely informative (Rutherfurd must have a crack team of researchers). If you ever want a crash course in New York history from the Dutch settlers to 9/11, I recommend this book.

Rutherfurd writes sweeping epics of novels with titles like

New York

and

Paris

. They convey the history of a place through characters who happen, very conveniently, to be well-placed for all major events in that place’s history. They are contrived, but enjoyable and extremely informative (Rutherfurd must have a crack team of researchers). If you ever want a crash course in New York history from the Dutch settlers to 9/11, I recommend this book.

The treatment of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire comes about two-thirds of the way through. Anna Caruso, a recent Italian immigrant to New York with her family, is thrilled when she lands a job at the Triangle Factory. She is also singled out to represent the garment workers at a lunch given by the wealthy Rose Master. Following that lunch, affluent women begin to support an ongoing garment workers’ strike, and a union is born. Rutherfurd’s broad cast of characters allows us to get the perspectives of both a worker and a society lady, and we also learn about the “mink brigade,” a group of society women who were suffragists and campaigners for women’s rights. A few months later, when the fire breaks out, its tragedy resonates.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire is such a signal event in American history that it’s likely to be the subject of many more works of art. However, it was particularly moving to see Berson’s quilt hanging at the cathedral opposite its counterpart from the Bangladesh garment factory disasters. The fact that these horrific events continue to take place should make us all more aware of the hidden costs behind our cheap clothing. (A filmmaker called

Andrew Morgan

is currently making a documentary about this called

The True Cost

; it has been funded by a

Kickstarter campaign

and looks as though it will be excellent.)

The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire is such a signal event in American history that it’s likely to be the subject of many more works of art. However, it was particularly moving to see Berson’s quilt hanging at the cathedral opposite its counterpart from the Bangladesh garment factory disasters. The fact that these horrific events continue to take place should make us all more aware of the hidden costs behind our cheap clothing. (A filmmaker called

Andrew Morgan

is currently making a documentary about this called

The True Cost

; it has been funded by a

Kickstarter campaign

and looks as though it will be excellent.)

Adding to the emotional power of the quilts is the fact that they are being displayed in the cathedral at the same time as Xu Bing’s amazing and politically resonant Phoenix sculptures. A few years ago, Xu, the newly instated president of the Beijing Central Academy of Fine Arts, was asked to create a sculpture for that city’s World Financial Center, then under construction. Visiting the site, Xu was shocked by the primitve conditions of the workers and, to honor them, decided to create two giant phoenixes made entirely from construction debris collected at the site.

Needless to say, an artwork announcing China’s sloppy building standards to the world would have been hugely provocative. When the developers realized what Xu was doing, they requested that he encase the sculptures in crystal to make them more palatable. (This is reminiscent of the scandal that occurred in 1934 when Diego Rivera was asked to excise a portrait of Lenin from his monumental Man at the Crossroads mural for the brand new Rockefeller Center). Like Rivera, Xu refused, and his work was rejected by its commissioners. Since then, the two phoenixes have been displayed at various locations in China and the U.S., but perhaps no place honors them more than their current location. They literally soar through the nave, the lights on their bodies twinkling, as if bound for Heaven. Another great reason to visit the Cathedral of St. John the Divine this summer.

———————————————————-

Across the Centuries, Across the Continents: Triangle Fire and Bangladesh Garment Workers Memorial Quilts is on view through Labor Day, 2014. Phoenix: Xu Bing at the Cathederal is on view through the end of 2014.Find out about visiting the Cathedral of St. John the Divine here .

Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition supports education, art and activist efforts about the Triangle Fire. It also has an open archive on its website, and recently sponsored a design exhibition for a permanent Triangle Fire memorial.

8 comments on “ Triangulated ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Terrific post, Sarah! Will have to checkout the quilts at the Cathedral.

Thanks, Robin! Plenty of opportunities to get to the cathedral 😉

This was a wonderful read and has taught me about something of which I knew nothing. Thank you for sharing. You have also given me some books to chase up which is always welcome. Happy weekend!

Thanks, Julia! Glad you enjoyed reading. Another recent novel that I loved, but didn’t mention in the article, is ‘Fever’ by Mary Beth Keane. It’s a fictional imagining of the story of Mary Mallon, better known as Typhoid Mary. There’s a scene where Mary is wandering in the Village and just happens to witness the Triangle fire. The author uses it to underscore how badly women like Mary were treated by their employers in the early years of the 20th century. (I’d recommend this over ‘Triangle.’)

What an interesting post Sarah! I am teaching Summer School at the Cathedral School at the moment so I will make sure I visit the exhibitions. Thank you!

Thanks, Lynette! I hope your summer is going well. Nathan and Zoe are in camp at the cathedral for two more weeks, hope we’ll bump into you!

A very interesting story particularly as the Bangladesh garment factory fire still resonates in Britain.

I thought your inclusion of the silent film based on the event was a very clever touch.

Well done, Sarah.

A very interesing post about a subject I didn’t know anything about – the echoes still reverberate in our explotative world of cheap labour.