Shooting High: Art Takes on New York’s Tallest Building

Good things come to those who wait

, we’re sometimes told. In the case of

One World Trade Center

, the soon-to-open building popularly known as the Freedom Tower, is that the case? The structure has taken thirteen years to complete, its construction delayed by countless squabbles, redesigns and political machinations. Of course, this is a skyscraper with huge symbolism—one that serves both as a glass-and-steel eulogy to its predecessors and a phoenix rising from their ashes—so expectations are high. Could any building carry the weight of that load?

Good things come to those who wait

, we’re sometimes told. In the case of

One World Trade Center

, the soon-to-open building popularly known as the Freedom Tower, is that the case? The structure has taken thirteen years to complete, its construction delayed by countless squabbles, redesigns and political machinations. Of course, this is a skyscraper with huge symbolism—one that serves both as a glass-and-steel eulogy to its predecessors and a phoenix rising from their ashes—so expectations are high. Could any building carry the weight of that load?

By now, the terror attacks of 9/11 have served as a plot point or motif in many works of art. I just counted fourteen that I’ve been exposed to (without particularly seeking them out), projects that run the gamut from an inspired and cathartic pop album to a searing documentary photography project (below) to an earnest collection of short films to a Broadway play . (If you want to do your own count, check out this helpful Wikipedia page ).

It’s hardly surprising, then, that even before its opening, One World Trade Center has already featured in works of art. On a recent visit to Chelsea galleries, I saw two photography projects that used the construction of the building in ways that couldn’t be more different. The contrast between the two was fascinating. While one referred back to a long tradition of documentary photography and employed its methods, the other used cutting-edge technology to translate construction scenes into visually stunning near-abstractions.

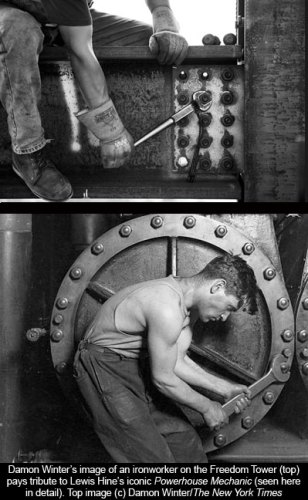

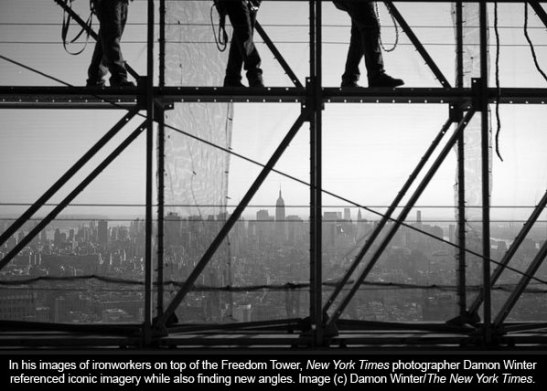

The first, Damon Winter’s Sky Cowboys , is a multimedia piece that is part of an exhibition of photographs from the New York Times Magazine at the Aperture Gallery. The short video features Winter’s photographs of construction workers at One World Trade Center, along with excerpts from recorded interviews with them. Shot in 2011, the photographs and video were published to coincide with the tenth anniversary of 9/11.

Winter is a talented photographer, and his black-and-white photographs of workers on the skeleton of the building are eloquent and aesthetically bold. While the choice of black and white seems like a direct historical reference to Lewis Hine’s 1930s images of steelworkers on the Empire State Building , Winter manages not just to repeat the expected tropes (and occasionally pay direct tribute to them—see below), but to create some unexpected images. In one of these, three sets of feet stroll a gangplank above a magnificent view of the city (above); in another, a tiny figure beneath a huge expanse of sky looks like a religious icon, but turns out to be a worker guiding a crane.

In the Aperture show, Winter’s work is represented only by the video that was created for the paper’s website. That’s a pity, because while the photographs are strong, I felt that as a multimedia project,

Sky Cowboys

fell a bit flat. Asked about their work, the men interviewed didn’t have much to say. Man after man, they resorted to clichés like “It’s hard work,” and “The view is amazing.” As Randy Kennedy tactfully put it in

an article about Winter’s subjects

, the ironworkers are not good at “doing what photographers do for them: standing outside themselves to articulate the almost Romantic-era daring of their job in a world of increasingly bloodless, prefab industry.” Or, as the exhibition wall text noted more simply, “Getting the ironworkers to talk about their work was not always easy.”

In the Aperture show, Winter’s work is represented only by the video that was created for the paper’s website. That’s a pity, because while the photographs are strong, I felt that as a multimedia project,

Sky Cowboys

fell a bit flat. Asked about their work, the men interviewed didn’t have much to say. Man after man, they resorted to clichés like “It’s hard work,” and “The view is amazing.” As Randy Kennedy tactfully put it in

an article about Winter’s subjects

, the ironworkers are not good at “doing what photographers do for them: standing outside themselves to articulate the almost Romantic-era daring of their job in a world of increasingly bloodless, prefab industry.” Or, as the exhibition wall text noted more simply, “Getting the ironworkers to talk about their work was not always easy.”

Along with Winter’s images in the multimedia piece, journalist and sound designer Pamela Chen creates an overlapping collage of the men’s voices along with sounds of construction. But despite this layering, the soundtrack feels somewhat banal. While I’m all for plain speak and certainly don’t expect ironworkers to be lyric poets, I felt that these particular words dragged the images down rather than letting them soar. The newspaper’s slide show , which featured just a few choice quotes on the side, felt more powerful.

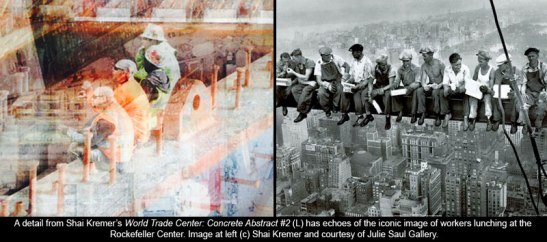

While Winter and Chen’s video featured traditional monochrome documentary photography and a layered sound collage, an exhibition by Israeli photographer Shai Kremer at the Julie Saul Gallery , World Trade Center: Concrete Abstract , featured visual layering and colors so intense that the images took on a vivid abstraction, while also clearly referencing the construction of One World Trade Center.

Like Winter, Kremer was given special access to the site in 2011, before the building topped out, when the ironworkers were doing the most dangerous part of the construction. He used a large format camera to capture extremely detailed images, then layered these on top of each other, also incorporating found photographs of the destruction after 9/11. Some images have as many as 100 layers, which Kremer says was a bit of a nightmare in terms of organization and storage.

There’s a lot of bad Photoshop work around, and it’s easy to imagine this project coming off like a high schooler’s earnest attempt to create something “deep.” If you’d blindfolded me and described these images before I saw them, I’m sure I would have dismissed them as a pretentious effort to make something arty or disguise weak photographs. I would have said that straight documentation of the site would have been the more humanist, emotive choice.

But I stand corrected. And I’m here to say that every once in a while, it’s nice to have one’s convictions not just overturned but blasted away. Because I was simply knocked out by Kremer’s images, and found them not just aesthetically rich but unexpectedly moving. I think that’s because their color fields have something of the richness and simplicity of a Monet or Rothko painting, but never take over to the extent that the subject matter is sidelined or obliterated.

Obviously, there are references in this work to both Italian Futurism and Cubism. But while those artistic movements were responding to the dynamism of the industrial age and the complexity of human perception, the fracturing and layering in Kremer’s work seems to symbolize the destruction and reconstruction of downtown Manhattan after the attacks. There’s something very cathartic about this, and the way the layering process combines with color and detail to create works that seem symphonic in their scope and ambition.

But if the images work as monumental abstractions, they also reward close study. Up close, one sees details of scenes and figures that enhance the overall emotional weight. For example, in image #2 I spotted a scene of three ironworkers having a peaceful interlude amid the din, eating their lunch while sitting on a steel beam—a scene that references the iconic (and currently uncredited ) photograph of men eating their lunch on a sky-high beam at the Rockefeller Center.

Interestingly, on his website Kremer uses a quote from the Communist Manifesto, “All that is solid melts into air,” as a way of evoking the impermanence of human life and man-made structures. This quotation is also the title of two books, a 1982 academic exploration of modernity by Marshal Berman ,and Irish writer Darragh McKeon ’s brilliant 2014 debut novel about the catastrophic 1986 nuclear power plant disaster at Chernobyl.

I read McKeon’s novel just recently, and was as awed by it as I was by Kremer’s images. Like Kremer, McKeon is interested in dissolution and rebuilding—in this case, the fracturing of the USSR, an empire that is already beginning to disintegrate when the Chernobyl disaster delivers a fatal blow. But don’t let me put you off: McKeon’s novel is no dry dissection of a moment of geopolitical history. Instead, it is a wonderfully vivid insight into that moment through a group of nuanced and compelling characters. Really, I can’t recommend it highly enough: see

my Goodreads review

for more details.

I read McKeon’s novel just recently, and was as awed by it as I was by Kremer’s images. Like Kremer, McKeon is interested in dissolution and rebuilding—in this case, the fracturing of the USSR, an empire that is already beginning to disintegrate when the Chernobyl disaster delivers a fatal blow. But don’t let me put you off: McKeon’s novel is no dry dissection of a moment of geopolitical history. Instead, it is a wonderfully vivid insight into that moment through a group of nuanced and compelling characters. Really, I can’t recommend it highly enough: see

my Goodreads review

for more details.

This is not a contest. Clearly there’s room for more than one kind of artistic representation of this particular moment in New York City’s building history, and clearly, One World Trade Center will feature in many more works of art. Some might be thoughtful documentations like Winter’s images; others might have imaginative flair like Kremer’s. And in the center of them all will be the building itself, skyscraper and monument, a site that will gather more associations and layers as the years pass by.

—————————————————————————

The New York Times Magazine Photographs is on view at the Aperture Gallery until November 1, 2014. For location and hours, click here .

World Trade Center: Concrete Abstract is on view at the Julie Saul Gallery until October 25, 2014. For location and hours, click here .

2 comments on “ Shooting High: Art Takes on New York’s Tallest Building ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

A fascinating look at One World Trade Center as a piece of art. I look forward to learning about more artistic comparisons.

I totally agree about “All that is solid melts into air” by Darragh McKeon. After getting into it it was a surprisingly easy read, and quite a page-turner. A few months ago I did not know that quote from the Communist Manifesto. Now, it seems to crop up all over the place.

It was fun to see Winter’s spanner photo next to Lewis Hine’s. I might have drifted through life unaware of either. Luckily, I learned about Hine via Sarah, in time to catch the exhibition’s progress through Madrid recently — thanks again.