Diane Arbus, Howard Nemerov and Sibling Rivalry

For the poet Howard Nemerov , photography “was the enemy of all that was mobile and enchanting and fluid and lovely about our short time on earth.” It was slightly inconvenient, then, that his sister was the acclaimed photographer Diane Arbus. At one point, Arbus gifted her brother a print of her most famous photograph, Identical Twins, Roselle, NJ, 1966 . It lay in a drawer in his living room, along with art supplies, developing cracks in the emulsion.

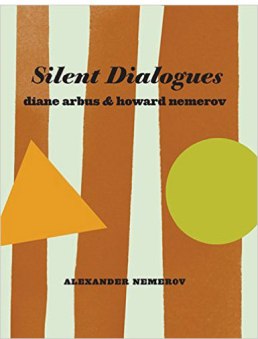

Alexander Nemerov, who tells this story in his book Silent Dialogues: Diane Arbus & Howard Nemerov , should know: he is Nemerov’s son and Arbus’ nephew. He is also an art historian at Stanford University, but his book is much less academic and more personal than the typical art history book. Examining connections between the famous siblings and their work, as well as his own responses to it, Silent Dialogues is intriguing, especially when presented—as I saw it recently, at the New York Studio School—as an illustrated lecture by its author.

Diane and Howard Nemerov grew up in privilege, the children of a department store owner. (When they went to play in sandboxes, their nanny insisted that they keep their white gloves on.) In her 1984 biography of Arbus,

Diane Arbus

, Patricia Bosworth writes that the two were “inseparable” as young children, since they both “possessed powerful, quirky intellects” and “read voluminously, absorbing knowledge and myths with ease.” But their childhood was not always happy: Howard remembered his father as “an overtly powerful, power-using sort of guy” and Diane compared the family department store, Russeks, to “some loathsome movie set in an obscure Transylvanian country.” Their glamorous mother laughed the two children off as “strange” because they were so studious.

Diane and Howard Nemerov grew up in privilege, the children of a department store owner. (When they went to play in sandboxes, their nanny insisted that they keep their white gloves on.) In her 1984 biography of Arbus,

Diane Arbus

, Patricia Bosworth writes that the two were “inseparable” as young children, since they both “possessed powerful, quirky intellects” and “read voluminously, absorbing knowledge and myths with ease.” But their childhood was not always happy: Howard remembered his father as “an overtly powerful, power-using sort of guy” and Diane compared the family department store, Russeks, to “some loathsome movie set in an obscure Transylvanian country.” Their glamorous mother laughed the two children off as “strange” because they were so studious.

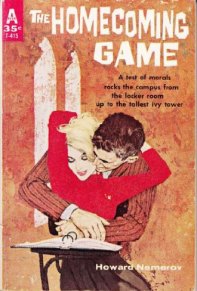

Still, despite this—or more likely because of it—they both flourished as artists. Between 1947 and 1980, Howard produced ten volumes of poetry and six books of fiction; he won the Pulitzer Prize in 1978 and the National Medal of Arts in 1987, and, from 1988 to 1990, was poet laureate of the United States. Arbus, meanwhile, had a successful career making commercial photographs that morphed by degrees into the more artistic, unflinching and sometimes uncomfortable images for which she is celebrated.

In many ways, Arbus and Nemerov shared a sensibility. They were both voracious seekers of truth, and had a morbid cast of mind. “The apocalyptic imagination of both Howard and Diane is hard to miss,” Alexander Nemerov told the audience at the Studio School. In Howard’s 1980 poem By Al Lebowitz’s Pool , a perfect summer’s day inspires an elegy on time passing and “releasing life.” Diane, who committed suicide in 1971, famously dreamed of being on a burning ocean liner where “there was smoke in the air, people were drinking and gambling… There was no hope.” In response, she was “terribly elated. I could photograph anything I wanted to.” (I have written before about Diane’s own writing .)

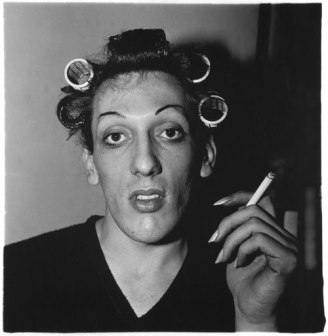

As it happened, her dream wasn’t far from reality. For the shy Diane, photography was “a licence to go whenever I wanted and to do what I wanted to do”—a philosophy that was borne out in images of midgets, transvestites, nudists and the mentally challenged. Though generally more circumspect and genteel, Howard showed flashes of the transgressive in his work too. In his first novel, The Melodramatist , a young woman’s psychoanalyst attempts to seduce her by showing her a photograph of a fetus—“its head gigantic, its eyes sunken black sockets… the mystery is concentrated back behind the eyes, he tells her.” The psychoanalyst keeps the photograph in his wallet, perhaps ready to whip out at any promising opportunity. Thus, an unsettling abuse of power is coupled with a pinch of the grotesque.

For Alexander Nemerov, that scene is notable “not [in] the gruesomeness of the photograph, and not the sinister situation in which it is shared…but rather the remorseless wish of these two people to get to the heart of things, down to essentials, to life itself.” Remorselessness, voracious curiosity, desire “to get to the heart of things”: this is a good description of both Howard and Diane’s work ethic.

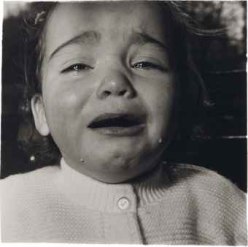

There, though, the similarities seem to end. Howard was a formalist poet , hewing to structure and propriety. He wrote Diane off as “a professional photographer, whose pictures are spectacular, shocking, dramatic, and concentrate on subjects perverse and queer.” He found her fascination with abnormality disturbing. “For this poet of flitting things, of dragonflies and cinnamon moths, of falling leaves and swimming koi, of the trellis, the stars, and the treetops between, her subjects were simply—and disgustingly—another world from his own,” Alexander Nemerov said.

It wasn’t just the subject matter, either, but the approach to it—Diane’s being intuitive while Howard’s was highly intellectual. “There is some gall, some chill, that my father portrayed in the world…a frosting over that was not confusingly mixed with his kindness,” Alexander Nemerov said. By contrast, Arbus had no protective shell, but was all wonder and rawness: “There is no wintry heart in Arbus’s photographs.”

Was Howard jealous of Diane? Rivalry and jealousy are “matters any polite account of art tries to avoid,” Nemerov said with a laugh. Nevertheless, he went on to suggest that his father probably did harbor jealousy, but that it acted as a stimulating force to his creativity. “A response in rivalry, in jealousy, if it is strong as well as weak, will also be a gathering down, a super-compression, of the rivaled-on person’s powers into some consolidations and star bursts that he did not know he had in him.”

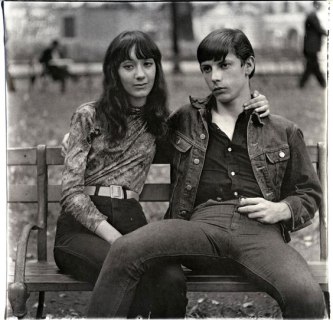

An Arbus photograph of siblings

Howard might have owned to this, subconsciously, in a 1963 essay he wrote about the poets William Wordsworth and William Blake, Two Ways of the Imagination , in which he casts Wordsworth as the gentle, passive beholder and Blake as the fiery visionary. “My father tends to identify himself more with Wordsworth, the nature poet,” Nemerov said. “And that leaves another person to be Blake.”

For her part, Diane seems not to have been jealous of her brother, or even conscious of his underlying feelings toward her. She appreciated his work, loving a 1959 story he wrote called A Commodity of Dreams , in which a reclusive man catalogues and files his dreams in a purpose-built library. Diane related intimately to this, seeing the catalogued dreams as equivalents of her photographs of “people who visibly believe in something everyone doubts.” For Howard, meanwhile, the man’s task was “a desperate and compromised endeavor.”

At the end of her life, Diane Arbus concentrated on

photographing the mentally challenged

—images that Howard must have found deeply troubling. Still, beneath his antipathy there was clearly deep affection, even admiration. At her memorial, he described their relationship as “ever so close, though owing to the chance of things [we were] not able to see [one another] in recent years, as much as we both would have liked.” Prior to that, in 1965, Arbus wrote to her brother that “the silent dialogue we have had all our lives on these matters is the more extraordinary for what we seem to have heard.”

At the end of her life, Diane Arbus concentrated on

photographing the mentally challenged

—images that Howard must have found deeply troubling. Still, beneath his antipathy there was clearly deep affection, even admiration. At her memorial, he described their relationship as “ever so close, though owing to the chance of things [we were] not able to see [one another] in recent years, as much as we both would have liked.” Prior to that, in 1965, Arbus wrote to her brother that “the silent dialogue we have had all our lives on these matters is the more extraordinary for what we seem to have heard.”

—————————————————————–

A fascinating article on Diane Arbus in The Guardian .

Howard Nemerov’s poem for Diane To D-, Dead by Her Own Hand .

Buy Silent Dialogues here .

6 comments on “ Diane Arbus, Howard Nemerov and Sibling Rivalry ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

So interesting to me in the context of the vlogs I am doing: The uneasy relationship between the written word and the visual, wordless world. Thanks for this perspective.

Thanks, Geoffrey. Do you have a link to your vlogs?

Hi. Here it is: https://goo.gl/uWNdt9

Fascinating – thank you.

i like your article, very inspiring and thank you for your post

nice