Mother Lode: An Interview with Ali Smith

Ali Smith at home. Image © Sarah Coleman

Mothers’ Day is just around the corner, and if you’ve had it up to here with chocolate hearts and perfumed soaps and schmaltzy messages on flowery greeting cards, you might want to consider a different kind of gift. How about a photo book that tells it straight, acknowledging the exhaustion and aggravation of motherhood along with its triumphs and joys? A book that celebrates all kinds of moms: the ones facing illness, raising children alone, battling demons; the ones who’ve adopted children or had them through a surrogate, who didn’t bond instantly with their children or who struggled to maintain a high-profile career after giving birth?

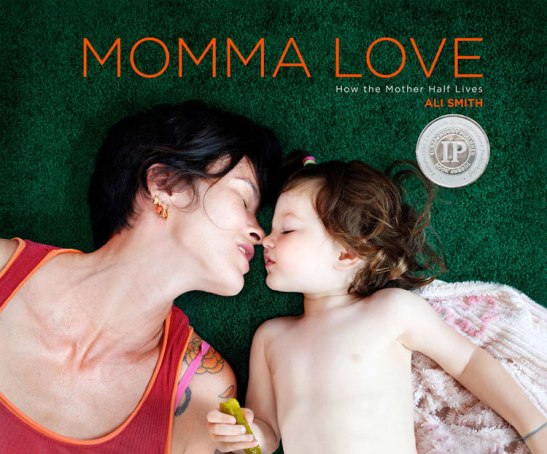

Ali Smith ’s book Momma Love: How the Mother Half Lives is just such a book. In intimate photographs and revealing texts, it offers an honest, unflinching look at the complexity of motherhood. The forty moms profiled cover a wide spectrum of experience, from a single mom who works as a clown to a Muslim-American mom who describes the social pressure she faced to have a son. Smith’s photographs are loose and candid, capturing everyday moments that inevitably include inconveniences such as tantrums, boo-boos and the necessity to breastfeed. They affirm Smith’s belief, as she writes in her introduction, that “admitting to the complexity of the situation doesn’t negate the love.”

Given the intimacy of the book, it seemed appropriate to hold our interview in Smith’s Lower East Side apartment—a colorful space filled with her six-year-old’s toys, photographs (her own and her photographer husband’s) and two black-and-white cats. Though she studied visual arts and photography in college, Smith also had a successful career as a rock musician before coming to photography full-time. And she had the distinction, as a child ballerina, of playing the head rat in The Nutcracker in Berlin against Rudolf Nureyev’s lead (“We kids once pulled off his wig onstage,” she recalls).

Diana in the hospital. Image © ali smith photography, alismith.com

In person, Smith is as charming and genuine as her photographs. A fierce advocate for women’s rights, she has photographed female convicts and mothers of children killed by gun violence; after Hurricane Sandy, she donated portrait sessions to people who had lost their family photographs in the flood. As a special Mothers’ Day offer this year, for every copy of Momma Love sold through her web site, Smith will donate $10 to Women in Need (WIN) NYC , an organization that helps women and children struggling with homelessness.

You started Momma Love before you were a mom yourself. What inspired you to photograph moms?

There were a few different things. In my mind it was a natural continuation of the work I’d done about unconventional women for my first book, Laws of the Bandit Queens , and my exploration of the totality of women’s lives—which doesn’t mean that a woman has to be a mother, but just that at some point in life she’ll probably address whether to be one or not. Then, too, at around the time I started this project I became a stepmother to a daughter I adore. Since we were so connected, but not by blood, I really wanted to understand what makes a family. Also, I had come from a family where my mom had seemed overly burdened by the role, which frightened me. So it was a personal exploration coming from a feminist perspective. It was prompted by my interest in women’s lives, and my beliefs in equality and fairness.

Hannah and Lizzie. Image © ali smith photography, alismith.com

In another interview, you said you wanted to “present an honest portrayal of [motherhood] to counter the copious amounts of slanted B.S.” on the subject. So what do you think are the most annoying stereotypes and clichés about motherhood?

Oh my God! They’re everywhere, and honestly, they can do your head in! It’s the idea that you’ve got to be placid, have four kids on your hip and be okay about it all the time! And even if you do get ruffled, you still have to look good! Not just you, but everything around you; there shouldn’t be any throw-up anywhere. On one level we all know that’s bullshit, and we joke about it, but on another level it affects all of us and it’s deeply damaging. So I’d like to push back.

Melanie and Lionel on the floor. Image © ali smith photography, alismith.com

In terms of making the images, how did you go about getting beyond those stereotypes and clichés? How long did you hang out with the women, and what discussions did you have with them?

I’m really genuinely interested in people, and when people sense that, I think they want to open up. It can be hard to capture a photo of someone in an unguarded way, because everyone’s got their photo face and you have to get past that. I’ve gotten pretty good at seeing what a person’s photo face is and trying to undo it, whether that’s by getting them to close their eyes for a moment or talking to them a bit more, or simply carrying on until they’re too bored to make it (this works well with kids)! Obviously the more time you have with someone the better, although sometimes you do just get lucky and get the magic moment rather quickly. There are two or three people whose images never made it into the book because I never quite got the photo that told the story. They had a great story, but for some reason I couldn’t capture it in the photo. I was really sorry to lose them, but I wasn’t going to undermine their beautiful stories with pictures that weren’t compelling.

Ngodup and Chogkey at the swings. Image © ali smith photography, alismith.com

Some of these women you knew already, but how did you find the others?

Once you’re attuned to a subject, you tend to pick things up. For example, I’d be at a party and someone would mention a friend who was having a baby with the help of a gay couple, and I’d kind of tune everything else out till I had the opportunity to pry more about it. The truth is, motherhood is rarely linear and easy, and everyone has interesting stories. Then my friends started having babies as we got older. And if I got interested in something that I didn’t have access to, I’d Google it and find someone. For example, I was curious about how breastfeeding moms managed in the workplace, and through looking that up I found Sophie Currier, who went to court to petition for extra time to sit her medical boards when she was breastfeeding. She wanted an extra hour of break to pump milk, and the National Medical Board Examinations fought her tooth and nail. Eventually she took the case to the Supreme Court of Massachusetts, and won, and her victory helped change laws in the workplace around breastfeeding mothers. But she also took a lot of flak for having made a stink.

Sophie and Lea at the lake. Image © ali smith photography, alismith.com

I love this picture of the mom and baby in the subway, next to the mosaic of the mother kangaroo feeding her baby.

That was a woman I’d worked with years back at a publishing house. She was always put together, gorgeous, accomplished and organized: her desk was insanely tidy, and you’d see her and think, I wish I was that person. But in the book she talks about how it was born out of being raised by parents who had her when they were teenagers, and having alcoholism in the family, and wanting to avoid that chaos. She struggled with the work-life balance after having children, and eventually became a freelancer and moved out of the city. It’s so interesting to find out what’s really going on for people, and what can be beneath the surface.

Alicia and Ari. Image © ali smith photography, alismith.com

Tell me about the image further up on this page, of the Tibetan nanny with her daughter at the swings.

Well, you know there’s a whole nanny culture in New York: women leave their families in other countries to come raise mostly Caucasian children in New York. It’s a bizarre dynamic. The woman in my photograph has a severely autistic child who she leaves all day with a nanny so that she can go nanny another family’s children. To me that’s a really interesting subculture that reveals all kinds of imbalances of class and race.

Felicia, serving 15 years to life for murder, with her son. Image © ali smith photography, alismith.com

Speaking of subcultures, I saw that a while back you did a story about women prisoners bonding with their kids.

Yes; it came from a similar place. A lot of women are in prison for non-violent crimes, or for violent crimes related to domestic violence, where they finally lashed out after years of abuse. And the punitive nature that we have as a country alarms me. We’re not really into prevention, we’re into pointing the finger and punishing. It’s short-sighted, it makes no sense and we know that, but we don’t want to put any effort or money into doing things differently. And I thought this program I photographed in Bedford Hills was beautiful: they were allowing women convicts to parent their babies for 12-18 months and teaching them about parenting. Those children hadn’t done anything wrong and they’re on the front lines of society. Let’s give them a good start where they feel loved and secure, then they might make better choices for themselves than their mothers were able to. The most compelling stories for me are ones where I can point out injustice, or social laziness and unfairness. And women get a great heaping helping of it in this world, so there’s no shortage of angles and stories.

What are you working on now?

I’ve been moving more into photo-documentary work. I recently did a story for The Guardian about mothers who’ve lost children under the age of 19 to gun violence. It’s a subject close to my heart. I think no one has more right than the mother to speak about the issue of what it’s like to lose a child to gun violence. I’ve experienced that pain only vicariously through these women. I particularly wanted to give them a voice because many of them work tirelessly, making it their job to campaign on this issue, and nobody really gives a shit. I’m always shocked by how many people have to have something bad happen to them in order to really care about it. I find that appalling, in part because I’d hope that if something as isolating and painful as that happened to me, people would truly listen and try to help me.

Oxsana Naumkin with a picture of her son. Image © ali smith photography, alismith.com

A lot of your work includes texts from the women telling their stories in their own words. How do you think the words and images work together—are they serving distinct or complementary purposes?

I think they have a nice balance. As we know, a photo is not objective reality, but it gives you a lot of information about someone. If you’ve got a compelling photo with some insight to it, it can reveal things beyond the surface—maybe things the person didn’t even intend to reveal. But a photo is also my interpretation of them, and it’s about our relationship; nobody else is going to be able to make that exact same picture of them. As far as the texts go, I can say that in all of my work I really want to help give a voice to people who are underserved and under-represented. I really wanted these texts to be in the women’s own words, and our interviews were a bit like diaries—once they were opened, I couldn’t believe how frank people were. It was almost as if they were waiting to be asked. For example, Rashida is a Muslim-American woman who talks in the book about the cultural pressure she faced to have a boy, which I think is extraordinary. There are very few forums where a woman like Rashida can speak about this, and know that the only agenda is for us to hear her experience.

Rashida and Burhanuddin on the roof. Image © ali smith photography, alismith.com

As someone who’s reported from the trenches, how much optimism do you have that things are shifting or will shift in future?

If you mean in terms of parenting equality, if I start at my home and work outward, I’m optimistic because my husband has a huge amount of awareness and is incredibly involved, and we’re raising a son who’s seeing what an involved father is like. What I’d really like to see is for women not to be undermined and punished for becoming mothers. If you’ve read The Price of Motherhood , you’ll know that the rate of poverty for women in old age increases exponentially if they’ve had children, because of their loss of income, paying into Social Security, career derailment, and lack of partner and social support. So there are these cultural punishments for doing the crucial job of raising well loved, secure and healthy people. I think it’s changing a bit. I hope it changes more.

Kitty Love: Ali Smith at home with her cat Luna. Image © Sarah Coleman

Let’s end by bringing it back from the political to the personal: What have been your greatest struggles and joys as a mother?

I definitely do struggle, sometimes, with the feeling that I’ve disappeared. My husband is a photographer and does quite well, so I have a direct in-house comparison to show how well I am or am not doing in my career! At the same time, there is this private joy that you get from being a mother, and you can’t really explain it, and it doesn’t prove anything or impress anyone, necessarily, but it just makes you so deeply happy. As the actress Amy Ryan says in the book, caring less about other things is like taking off a heavy coat. I try to treat my parenting in the same way as I treat every aspect of my life—in other words, like an artist. Be as creative with it as you can be, as involved as you can be, as in the moment as you can be, and strive to make it meaningful. Those are my mantras.

Visit the MommaLove store here .

3 comments on “ Mother Lode: An Interview with Ali Smith ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Great interview.

Best wishes

Christiane Monarchi

Christiane Monarchi Editor, Photomonitor (www.photomonitor.co.uk)

On Wed, May 4, 2016 at 4:36 PM, the literate lens wrote:

> sarahjcoleman posted: ” Mothers’ Day is just around the corner, and if > you’ve had it up to here with chocolate hearts and perfumed soaps and > schmaltzy messages on flowery greeting cards, you might want to consider a > different kind of gift. How about a photo book that tells it ” >

I love the pictures and the interview, so vively and genuine. Paola

Fantastic article. The photos are a nice antidote to curated social media images. The interview was great, and thought-provoking. The Price of Motherhood certainly sounds like the sort of book Mervyn Griffiths-Jones would not have wanted his wife or servants to read(!).