The Strange Case of the Nanny Photographer

Like thousands of other people, I’ve been captivated by the posthumously published photographs of Vivian Maier. In case you don’t know, Maier was a Chicago nanny who, beginning in the 1950s, roamed the city on her days off and took vibrant, sensitive images of people and street scenes.

Like thousands of other people, I’ve been captivated by the posthumously published photographs of Vivian Maier. In case you don’t know, Maier was a Chicago nanny who, beginning in the 1950s, roamed the city on her days off and took vibrant, sensitive images of people and street scenes.

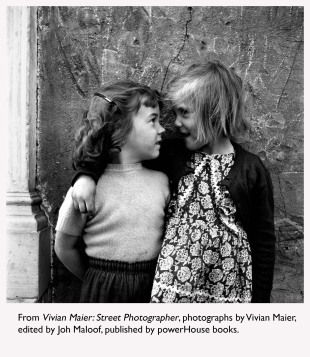

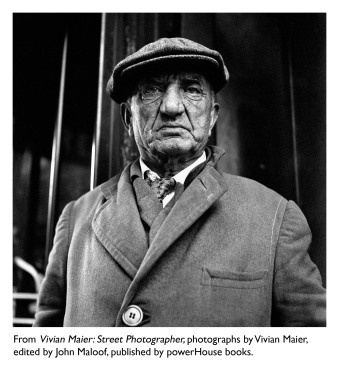

At their best, her images rank right up there with the finest street photography of the twentieth century–but until recently they were languishing in a storage unit. It was only when the contents of the storage unit were auctioned that Maier’s amazing body of work was discovered.

Maier, who died unrecognized in a nursing home in 2009, has become a bit of an art world sensation since then. You can catch her work until January 28th in both New York and Los Angeles , and last month powerHouse Books released a monograph called Vivian Maier: Street Photographer .

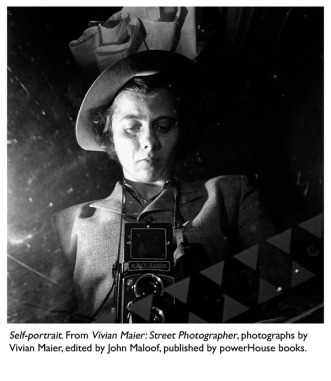

The images are wonderful by themselves, and Maier’s life story only adds to the interest. Born in the Bronx to a French mother and an Austrian father, she lived in Europe as a child and returned to the U.S. in her twenties, apparently severing her family ties. The children she looked after remember her fondly as a Mary Poppins figure, but she was friendless and fiercely private, showing her photographs to no-one. Yet she clearly loved the serendipitous clutter of street life and was able to capture stunningly perceptive, intimate portraits of strangers.

The images are wonderful by themselves, and Maier’s life story only adds to the interest. Born in the Bronx to a French mother and an Austrian father, she lived in Europe as a child and returned to the U.S. in her twenties, apparently severing her family ties. The children she looked after remember her fondly as a Mary Poppins figure, but she was friendless and fiercely private, showing her photographs to no-one. Yet she clearly loved the serendipitous clutter of street life and was able to capture stunningly perceptive, intimate portraits of strangers.

In his foreword to the powerHouse monograph, novelist and photography buff Geoff Dyer writes that, as a nanny, Maier was “an outsider whose privileged access to domestic life permits the development of no gift other than observation.” (Check out Dyer’s interesting book of essays on photography, The Ongoing Moment .) Of course, that only partially accounts for Maier’s gift. As the book points out, a great street photographer must also have “an eye for detail, light, and composition; impeccable timing; a populist or humanitarian outlook; and a tireless ability to constantly shoot… and never miss a moment.” Maier had those qualities in abundance.

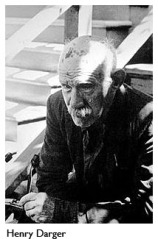

It’s a bit of a leap, but the discovery of her archive made me think of

Henry Darger

, the famous Chicago outsider artist whose work was also discovered posthumously. Both writer and artist, Darger wrote complex, labyrinthine stories that he illustrated with scrolls of beautiful watercolors. On the eccentricity scale, he was clearly further out than Maier. But they were both private, driven individuals who never showed their work. And it’s entirely possible that, on one of her Sundays walking on Chicago’s North Side, Maier might have stopped to consider a bald, beady-eyed old man in a threadbare coat, never pegging him as a fellow secret artist.

It’s a bit of a leap, but the discovery of her archive made me think of

Henry Darger

, the famous Chicago outsider artist whose work was also discovered posthumously. Both writer and artist, Darger wrote complex, labyrinthine stories that he illustrated with scrolls of beautiful watercolors. On the eccentricity scale, he was clearly further out than Maier. But they were both private, driven individuals who never showed their work. And it’s entirely possible that, on one of her Sundays walking on Chicago’s North Side, Maier might have stopped to consider a bald, beady-eyed old man in a threadbare coat, never pegging him as a fellow secret artist.

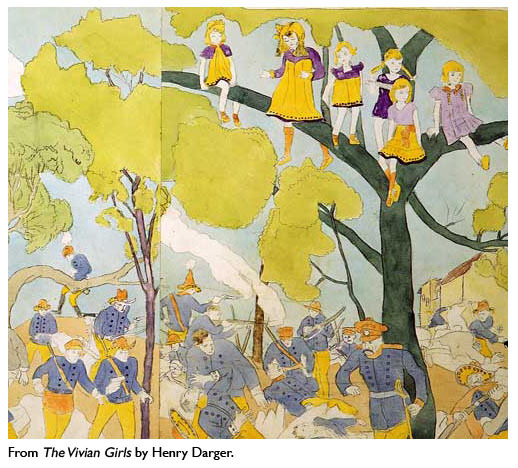

It’s a cute coincidence, too, that Darger’s magnum opus is called

The Story of the Vivian Girls

. (Its full title is much longer, as is only appropriate for a book of 15,145 pages.) I’m not going to make too much of that, except to say that as someone who obviously cared about children, Vivian Maier might have relished seeing her name in a book about rebel girls who take up arms to oppose child slavery.

How would Darger and Maier have felt about their fame? We’ll never know, and that brings a certain voyeuristic tension to the way we look at their work. I can at least say that, in looking at materials on Maier, I’ve been impressed by John Maloof, the young Chicagoan who discovered her. Though only twenty-six when this golden egg dropped into his lap, Maloof seems to be handling Maier’s estate with sensitivity and tact. Follow this link to see two short videos about Maloof and his great find, and this one for a discussion of other photographers whose work was discovered and championed by a third party.

I think we’re bound to hear more about Maier. The work on show is the tip of the iceberg: her archive includes some 100,000 negatives, undeveloped films, cameras, clothing, audio and videotapes. These materials could have ended up scattered all over Chicago, or buried deep in a landfill. Instead, they seem to have landed in the right hands–and that’s part of her amazing story too.

I think we’re bound to hear more about Maier. The work on show is the tip of the iceberg: her archive includes some 100,000 negatives, undeveloped films, cameras, clothing, audio and videotapes. These materials could have ended up scattered all over Chicago, or buried deep in a landfill. Instead, they seem to have landed in the right hands–and that’s part of her amazing story too.

One comment on “ The Strange Case of the Nanny Photographer ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Wonderful piece, Sarah. This takes the Vivian Maier discussion far beyond the reams of blather that have already been wasted on the subject. I suspect that the more we learn about Ms. Maier – if we do learn more – that we are likely to discover she was mad as a hatter. But that won’t detract from her unquestionable talent, but rather will make her and it even more intriguing, and perhaps add to the discussion about madness and genius.