The Woman Who Destroyed the Photo League

There’s a wonderful exhibition on now at the Jewish Museum called The Radical Camera . It tells the story of New York’s Photo League, which was active from 1936 to 1951. A scrappy leftist organization, the Photo League drew in big names like Paul Strand along with aspiring unknowns. Uniting them was an interest in urban culture and a desire to address social problems through photography. Cameras in hand, they roamed the streets of the Lower East Side and Harlem, where children played in abandoned buildings and garbage littered the streets.

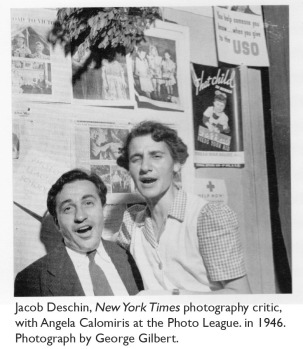

Part of the lore of the Photo League is the way it ended. In 1951, three years after being blacklisted for suspected communist activities, the organization imploded. This was largely due to the testimony of

Angela Calomiris

, a League member who was also an F.B.I. informant. Greek-American, from a modest background, Calomiris was by all accounts a friendly and well-liked woman, and a competent (if uninspired) photographer. When her colleagues found out she’d been informing on them for years, it shocked them to the core.

Part of the lore of the Photo League is the way it ended. In 1951, three years after being blacklisted for suspected communist activities, the organization imploded. This was largely due to the testimony of

Angela Calomiris

, a League member who was also an F.B.I. informant. Greek-American, from a modest background, Calomiris was by all accounts a friendly and well-liked woman, and a competent (if uninspired) photographer. When her colleagues found out she’d been informing on them for years, it shocked them to the core.

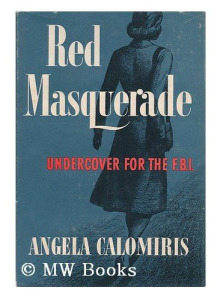

I was curious to know more about Calomiris, so I ordered her memoir,

Red Masquerade: Undercover for the F.B.I.

The book was published in 1950, less than a year after Calomiris’s evidence helped convict eleven high-ranking Communists in a famous trial. Its cover, which shows the retreating back of a shapely woman, seems to play on the idea of her as a Mata Hari seductress who used feminine wiles in the service of her country.

I was curious to know more about Calomiris, so I ordered her memoir,

Red Masquerade: Undercover for the F.B.I.

The book was published in 1950, less than a year after Calomiris’s evidence helped convict eleven high-ranking Communists in a famous trial. Its cover, which shows the retreating back of a shapely woman, seems to play on the idea of her as a Mata Hari seductress who used feminine wiles in the service of her country.

The truth is less glamorous and a lot more nuanced. Not surprisingly, Calomiris fails to mention that she was a lesbian—a fact that certainly wouldn’t have endeared her to her 1950s readers. In fact, a few former Photo Leaguers have speculated that the F.B.I. drew her in by threatening to expose her sexual orientation, but that seems unlikely. Calomiris describes her handlers too lovingly for that—but no doubt, the fact that she wasn’t likely to marry and have children made her a good government investment.

Other things made Calomiris the perfect double agent too. She explains, early in the book, that the F.B.I. was looking for people who could fit seamlessly into the Communist Party, people “who have had a hard row to hoe and look as if they could be persuaded to stop trying.” Calomiris’s poor background and work ethic made her a shoo-in, and her status as a first generation immigrant (someone who wanted to prove her worth to her country) sealed the deal.

It’s funny to read

Red Masquerade

now, when Communism is mostly a spent force. The book transports the reader back to a time of secret meetings, neighbor-on-neighbor informing and general paranoia. Whether or not you believe the American Communist Party had the means or even the desire to overthrow the U.S. government, there can be no doubt that Hoover’s F.B.I. took it very, very seriously.

It’s funny to read

Red Masquerade

now, when Communism is mostly a spent force. The book transports the reader back to a time of secret meetings, neighbor-on-neighbor informing and general paranoia. Whether or not you believe the American Communist Party had the means or even the desire to overthrow the U.S. government, there can be no doubt that Hoover’s F.B.I. took it very, very seriously.

Though more given to self-aggrandizement than introspection, Calomiris does attempt to answer the question of why she informed on her friends. She wanted to serve her country, she says, adding lamely that “it didn’t seem the kind of request that anyone could refuse.” Politically liberal, she was “naturally for the working man” and agreed with some Communist platforms. But she despised group-think, and found the Communists’ “fanatical emotional attachment to an abstract cause… not endearing.” All through the book she’s highly sarcastic about her Party colleagues, accusing them of everything from racism to terminal dullness, opining that “a surprising number of them were in the Party because they could find no other social life.”

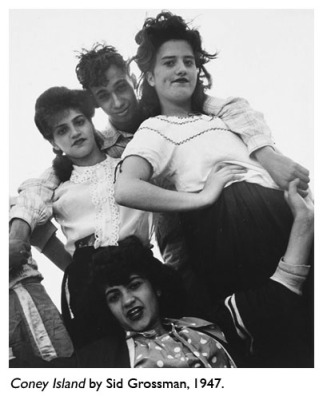

Whatever her motivations, one thing is sure: Calomiris was amazingly cold-blooded about her work. “I was being an actress, at times a hammy actress,” she writes, and, “it is easy to lie if you think of a lie as a tool.” She happily sold out Sid Grossman, the committed Photo League founder who was her photographic mentor. And in one of the book’s creepiest episodes, she comforts a Party friend who, having just been questioned by the F.B.I., has destroyed her Party card in fear. “I smiled to myself,” Calomiris writes proudly. “I had turned her card number in to the F.B.I. long before.”

Whatever her motivations, one thing is sure: Calomiris was amazingly cold-blooded about her work. “I was being an actress, at times a hammy actress,” she writes, and, “it is easy to lie if you think of a lie as a tool.” She happily sold out Sid Grossman, the committed Photo League founder who was her photographic mentor. And in one of the book’s creepiest episodes, she comforts a Party friend who, having just been questioned by the F.B.I., has destroyed her Party card in fear. “I smiled to myself,” Calomiris writes proudly. “I had turned her card number in to the F.B.I. long before.”

How deeply was the Photo League involved with Communism? That’s open to question. It started as the Workers Film and Photo League, which was unabashedly Communist—but it broke off in 1936. Grossman belonged to the Party, so did a few others, but many former members have said they never heard politics discussed there. For the purposes of the book at least, Calomiris seems sure the League was a front, its purpose being “to start a group of ‘politically undeveloped’ people moving in the right direction.” That belief is pretty convenient, since all it requires is one or two Communist members, and voila! The place is dangerously subversive.

Perhaps, as a ho-hum photographer, Calomiris dreamed of glory as a spy. If so, she was surely disappointed. After the trial she got some print and radio interviews; Eleanor Roosevelt called her “a young lady of great courage,” but interest in her soon waned. Her career as a photographer pretty much ended, she received death threats, and she left New York for Provincetown, where she opened a bed-and-breakfast in the 1960s.

Angela Calomiris worked for the F.B.I. from 1942 to 1949, during which time she doggedly exposed everyone she could. “In 1942, I was a photographer who, like many artists, paid very little attention to political theory,” she writes. By 1949, she was steeped in murky politics. For this dubious honor, she paid with her career—a fair price given the devastation she caused.

5 comments on “ The Woman Who Destroyed the Photo League ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

scrappy?

Yes, I think so. I chose that word because it was small, the premises were dirty and run-down, most members didn’t pay their dues, but the organization was ambitious and energetic. Here’s a description from Calomiris’s book:

“The Photo League was typical of many art orgnizations. It was informal, friendly, and badly-run… Everyone complained of the dirt, but no one did anything about it. The stairs were grimy. You could always tell a visitor, we used to quip, even if you couldn’t see his face. A visitor would be brave enough to grab the banister. We regulars knew how greasy it was and didn’t touch a thing we didn’t have to.”

Fascinating read!

This is a very interesting post. The exhibit at the Jewish Museum, The Radical Camera, includes 2 photographs by my father, N. Jay Jaffee. His photographs include well-known black-and-white images of New York during the 1940s and 1950s.

On his website, he writes about The Photo League and Sid Grossman, with whom he took classes in 1947: http://www.njayjaffee.com .

Thanks for this, Cyrisse! I will look for your father’s images when I go back to look at the show again, and I’ll check out his web site.