LIFE magazine in close up

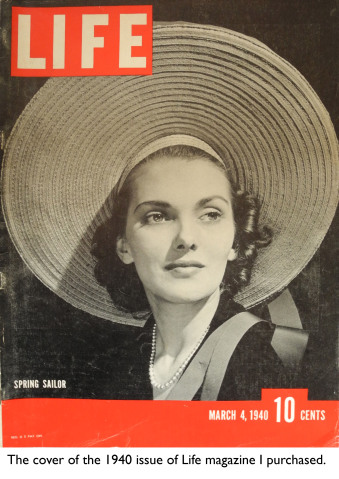

Last weekend, I was browsing in an antique store when I came across some issues of

Life

magazine dating from the 1930s and 40s. On a whim, I bought the 1940 issue that corresponds to this week, March 4th. We’re accustomed to seeing anthologies of the best of

Life

magazine, but I wondered what it would be like to read a run-of-the-mill issue cover to cover, as the magazine’s original readership did.

Last weekend, I was browsing in an antique store when I came across some issues of

Life

magazine dating from the 1930s and 40s. On a whim, I bought the 1940 issue that corresponds to this week, March 4th. We’re accustomed to seeing anthologies of the best of

Life

magazine, but I wondered what it would be like to read a run-of-the-mill issue cover to cover, as the magazine’s original readership did.

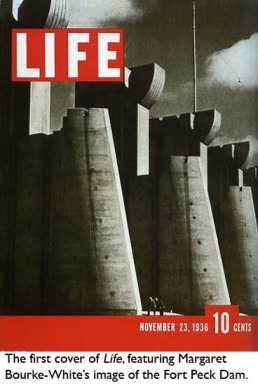

First, some history. In 1936, Time magazine founder Henry Luce bought a struggling general interest magazine called Life solely for the use of its name. He turned it into the first ever photojournalism-based news magazine, and recruited some of the world’s most talented photographers. Margaret Bourke-White and Alfred Einsenstadt were among the original staff photographers; others who contributed to the magazine over the years include Robert Capa, Phillippe Halsman and Gordon Parks.

Life dominated the market for four decades. To give you an idea how popular it was, it sold 13.5 million copies per week at its peak. Today’s Time magazine has around 12 million subscribers, but many of those are getting the magazine at virtually no cost in order to bump up figures for advertisers. (If you look at this Wikipedia page , there’s a suspicious 7 million jump in the circulation figures between 2009 and 2010.)

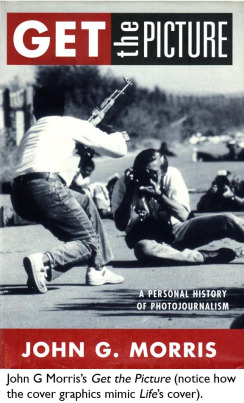

A great account of the early days of

Life

is given by illustrious photo editor John G. Morris in his 1998 memoir

Get the Picture

. Morris joined the staff of

Life

in 1938, just after he graduated, as a mailroom boy. His first tasks included running from the

Life

office to Grand Central Station at 5:30 with a pouch of pictures and copy for the Twentieth Century Limited’s 6:00 p.m. red-carpet departure to Chicago, where the magazine was printed. “If you missed the train,” he writes, “you need not bother to return to work the next day.”

A great account of the early days of

Life

is given by illustrious photo editor John G. Morris in his 1998 memoir

Get the Picture

. Morris joined the staff of

Life

in 1938, just after he graduated, as a mailroom boy. His first tasks included running from the

Life

office to Grand Central Station at 5:30 with a pouch of pictures and copy for the Twentieth Century Limited’s 6:00 p.m. red-carpet departure to Chicago, where the magazine was printed. “If you missed the train,” he writes, “you need not bother to return to work the next day.”

Morris writes compellingly about the glory days of Life . (He leads off with the exciting story of getting Robert Capa’s famous D-Day landing photos from Normandy–the rush to print them so intense that three out of four rolls of film were melted in the drying machine by accident.) But he’s also refreshingly honest about the commercial decisions governing Life . “We were entertainers as much as journalists,” he writes. “Photographers worked from ‘scripts’ and stories were ‘acts.’ …We had to ‘fill the book’ each week. It didn’t matter if we led off with a chorus girl or a cardinal, but there had to be a good mix because the magazine had to sell.” (In the age of Lohan and Kardashian, this sounds all too familiar.)

Another account of Life’s early days is given in Margaret Bourke-White’s excellent 1963 memoir Portrait of Myself (available as a free nook book here ). Already a famous photographer in 1936, Bourke-White was recruited by Luce at a starting salary of $12,000 (roughly $190,000 in today’s dollars.) The magazine’s writers were treated like nobodies next to Bourke-White, who was a bona fide star. “From the very beginning, the antics of the ‘crack photographer’ were central to the glamour and modernity of Life,” writes John Tagg in The Disciplinary Frame: Photographic Truths and the Capture of Meaning .

For her part, Bourke-White loved the work—and what wasn’t to like? She was given plum assignments by a magazine that valued her and printed her photo essays at loving length. “I woke up each morning ready for any surprise the day might bring,” she writes. “I loved the swift pace of the

Life

assignments, the exhilaration of stepping over the threshold into a new land. Everything could be conquered. Nothing was too difficult. And if you had a stiff deadline to meet, all the better. You said yes to the challenge and shaped up the story accordingly, and found joy and a sense of accomplishment in so doing.”

For her part, Bourke-White loved the work—and what wasn’t to like? She was given plum assignments by a magazine that valued her and printed her photo essays at loving length. “I woke up each morning ready for any surprise the day might bring,” she writes. “I loved the swift pace of the

Life

assignments, the exhilaration of stepping over the threshold into a new land. Everything could be conquered. Nothing was too difficult. And if you had a stiff deadline to meet, all the better. You said yes to the challenge and shaped up the story accordingly, and found joy and a sense of accomplishment in so doing.”

Case in point: for the magazine’s first issue, Bourke-White was assigned to photograph a chain of dams being constructed in Montana as part of the New Deal. She rode around on horseback and spent nights at the local bars. When she sent in her pictures (including one of a child sitting on top of a bar amid pints of beer), everyone was surprised. “What the Editors expected were construction pictures as only Bourke-White can take them,” Life wrote in an introduction to the essay. “What the Editors got was a human document of American frontier life which, to them at least, was a revelation.”

So now back to that March 4th, 1940 issue of

Life

I purchased the other weekend. Does it reveal anything surprising about the august publication?

So now back to that March 4th, 1940 issue of

Life

I purchased the other weekend. Does it reveal anything surprising about the august publication?

The first thing to say is that it is very much a document of its times. In other words, there are ample doses of both racism and sexism in its pages. When a reader criticizes Life for referring to Rumanians as slovenly Slavs (on the basis that they’re actually Latin), an editor responds, “the Rumanians are one of the most mixed-up racial stocks in Europe. Their Slavic blood, however, though not predominant, is the likeliest source of their slovenliness.” And in a feature on Miami, images of beach-going women are accompanied by this choice description: “Motivated by greed, exhibitionism, sociability or mere duty, they gather from all points and professions. No one can ever tell what they will be up to next.” Oh, those crazy, greedy women! Before you know it they might be… drinking a bottle of Coca-Cola!

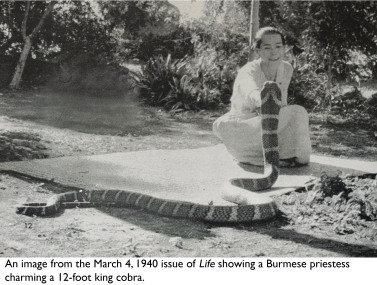

In other ways, the magazine is quite enlightening. There is (as you’d expect) a reasonable amount of war coverage, but there’s also an astonishing documentation of a ritual in which a Burmese priestess charms and kisses a 12-foot king cobra snake. (Like Bourke-White’s appointment, the depiction of this strong, brave woman is an interesting counterpoint to the beach beauties and compliant young wives the magazine features elsewhere.) There are stills from a movie about the doctor who found a cure for Syphilis, and a cute essay about “watching democracy work” at its most “molecular unit,” a tiny town hall meeting in Massachusetts. Less enlightening, but expected, are the pictures of starlets and pretty women in spring hats (one of which made the cover) and a slew of advertisements for everything from cars to corsets. A rather large number of ads are for dental hygiene products, featuring dramatic stories about men losing their jobs and ladies because of halitosis.

In other ways, the magazine is quite enlightening. There is (as you’d expect) a reasonable amount of war coverage, but there’s also an astonishing documentation of a ritual in which a Burmese priestess charms and kisses a 12-foot king cobra snake. (Like Bourke-White’s appointment, the depiction of this strong, brave woman is an interesting counterpoint to the beach beauties and compliant young wives the magazine features elsewhere.) There are stills from a movie about the doctor who found a cure for Syphilis, and a cute essay about “watching democracy work” at its most “molecular unit,” a tiny town hall meeting in Massachusetts. Less enlightening, but expected, are the pictures of starlets and pretty women in spring hats (one of which made the cover) and a slew of advertisements for everything from cars to corsets. A rather large number of ads are for dental hygiene products, featuring dramatic stories about men losing their jobs and ladies because of halitosis.

Just over a month ago, Time.com launched a new incarnation of Life on its web site. The new site draws from the impressive archives of Life : there are ‘behind the shot’ discussions of iconic images and portfolios of previously-unpublished pictures. The layout and navigation of the site are clean and simple, making it a pleasure to browse. The only improvement, in my mind, would be the addition of current photo stories. There are so many talented photojournalists working now, and so few venues for their work. Come on Life , how about giving them some space?

2 comments on “ LIFE magazine in close up ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Yet another enlightening entry, Sarah – thank you!

A few years ago a bought a number of old LIFE’s, a few of which contained classic photo stories, on of which was Larry Burrow’s “Yankee Papa 13,” about a helicopter mission in Vietnam, and another of which was Cartier-Bresson’s photos from Cuba. What really struck me, though, wasn’t the work of the “giants,” but the extremely mundane nature of what was in the magazine, and, as you note, the by-the-book quality of the photo journalism. In photography, as in any other area of journalism – or lower case life for that matter – we tend to remember the highlights, and over time come to believe that what really were exceptional highlights were the everyday stuff, even though they weren’t. We wouldn’t remember “Country Doctor,” or “Yankee Papa 13,” if work of that quality filled every issue of LIFE.

Very interesting read Sarah as always!

I agree with you; the ‘greatest hits’ collections from LIFE we know so well cherry-pick certain photo-essays and images which are them shown out of context and presented in a way that privileges them as examples of ‘great’ documentary photography.

So much more can be gleaned from examining them in context within the magazine itself. It just adds another layer to how they were viewed at the time as well as how we view and understand them today.