Clover Adams and Photographer Suicides

Witty, clever and rich, Clover Adams had almost every advantage in life. Born in 1843 to a prominent Boston family, she received an impressive education for a girl at that time. At twenty-eight she married Henry Adams, a brilliant intellectual and presidential descendant. The couple lived in Washington, where their dinner guests included cabinet secretaries and generals. Clover took up photography at forty, embracing it with passion—then, at age forty-four, she committed suicide by swallowing some of the potassium cyanide she used in her darkroom.

Witty, clever and rich, Clover Adams had almost every advantage in life. Born in 1843 to a prominent Boston family, she received an impressive education for a girl at that time. At twenty-eight she married Henry Adams, a brilliant intellectual and presidential descendant. The couple lived in Washington, where their dinner guests included cabinet secretaries and generals. Clover took up photography at forty, embracing it with passion—then, at age forty-four, she committed suicide by swallowing some of the potassium cyanide she used in her darkroom.

The mystery of her death is probed by Natalie Dykstra in the new biography Clover Adams: A Gilded and Heartbreaking Life . Dykstra writes that depression ran in Clover’s family, leading to suicide in at least one other case. For Clover, the depression was sudden, triggered by several events. Her beloved father’s death; her husband’s increasing emotional distance; her grief over never having children—together, these were the perfect storm that led her to take her own life.

Photographically, Clover seems to have been an inspired amateur rather than a pioneer. Her photographs are often melancholy, showing isolated figures and trees—even when there are several people in the frame, they’re looking away from each other. As Dykstra notes, “creativity can be compensatory, redemptive, a release, a reach toward freedom and hope. But this is not always the case. …Things can sometimes go the other way. Creativity also undoes, overwhelms, gives power to hidden undertows. What’s brought forward in expression is exposed and becomes irrefutable.”

Photographically, Clover seems to have been an inspired amateur rather than a pioneer. Her photographs are often melancholy, showing isolated figures and trees—even when there are several people in the frame, they’re looking away from each other. As Dykstra notes, “creativity can be compensatory, redemptive, a release, a reach toward freedom and hope. But this is not always the case. …Things can sometimes go the other way. Creativity also undoes, overwhelms, gives power to hidden undertows. What’s brought forward in expression is exposed and becomes irrefutable.”

Reading Clover Adams made me think of other photographer suicides. Next to writers, photographers seem like a relatively life-loving bunch—Wikipedia lists hundreds of writer suicides , compared with just eleven photographer suicides . Nevertheless, there have been some notable photographer suicides—most prominently, Diane Arbus and Francesca Woodman.

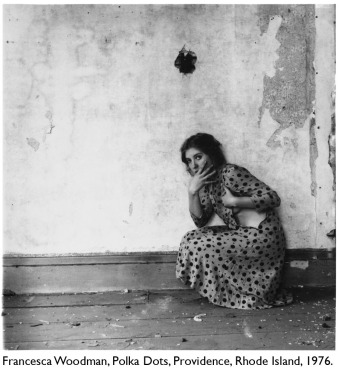

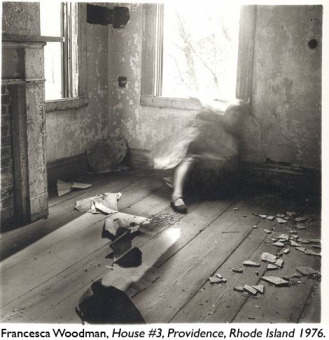

In both Arbus and Woodman’s cases, like in Adams’, hints of a troubled psyche lurk in the images. Arbus was almost magnetically drawn to misfits, from her giants and dwarves to the mentally disabled patients she photographed at the end of her life. Woodman, on the other hand, focused almost exclusively on herself, shooting haunting, intense self-portraits in barren landscapes and dilapidated houses.

Only twenty-two when she took her life, Woodman had already amassed an impressive body of work. Some of her images seem anguished, others are more playful. Depressed over losing a grant and a boyfriend, she gave way to the darkness that hovers at the edges of her images. Arbus, too, was depressed over a lack of assignments—compounded by the fact that she felt she’d lost her creative drive. In Patricia Bosworth’s 1984 biography

Diane Arbus

, sculptor Nancy Grossman describes an encounter with Arbus two weeks before her death:

Only twenty-two when she took her life, Woodman had already amassed an impressive body of work. Some of her images seem anguished, others are more playful. Depressed over losing a grant and a boyfriend, she gave way to the darkness that hovers at the edges of her images. Arbus, too, was depressed over a lack of assignments—compounded by the fact that she felt she’d lost her creative drive. In Patricia Bosworth’s 1984 biography

Diane Arbus

, sculptor Nancy Grossman describes an encounter with Arbus two weeks before her death:

“She spoke… about her work, which, she cried, was giving her

nothing back

… And listening to her, I thought this must be the most devastating thing for an artist—to lose one’s need to discover. What does it mean when suddenly, inexplicably, we’re no longer nourished by our work and it gives us nothing back?”

“She spoke… about her work, which, she cried, was giving her

nothing back

… And listening to her, I thought this must be the most devastating thing for an artist—to lose one’s need to discover. What does it mean when suddenly, inexplicably, we’re no longer nourished by our work and it gives us nothing back?”

This reminded me of a passage in Clover Adams , where Clover laments to her sister that she has lost her very sense of self. “Ellen, I’m not real—Oh make me real—you are all of you real!” she cries.

Although all of these three cases are women, I wouldn’t want to draw any hasty conclusions about women photographers and suicide. Women photographers often create intensely personal, probing bodies of work, but there are many who do so— Imogen Cunningham , Sally Mann , Elinor Carucci —without tipping into darkness in their personal lives. I can also think of male photographers who’ve mined their own psyches and life histories in their work ( Robert Mapplethorpe , Duane Michals and Keith Carter come to mind), and male photojournalists like Kevin Carter who’ve committed suicide as a result of the atrocities they’ve witnessed.

I think of suicide as being a bit like a plane crash, in that several key elements—in this case, chronic depression and a sudden trigger or impulse—need to come together. In the 1990s, I spent two years staffing a suicide prevention line in the Bay Area. The callers ranged from people who were a little down and needed a boost, to people whose depression was chronic and paralyzing. Our training taught us to conduct a risk assessment, but I suspect it wasn’t very accurate, and that some of the perky-sounding callers might have been the ones who ended up taking action. Mostly I was there to listen and be sympathetic; to acknowledge the caller’s pain and make them feel, for a few minutes, not quite so alone.

I think of suicide as being a bit like a plane crash, in that several key elements—in this case, chronic depression and a sudden trigger or impulse—need to come together. In the 1990s, I spent two years staffing a suicide prevention line in the Bay Area. The callers ranged from people who were a little down and needed a boost, to people whose depression was chronic and paralyzing. Our training taught us to conduct a risk assessment, but I suspect it wasn’t very accurate, and that some of the perky-sounding callers might have been the ones who ended up taking action. Mostly I was there to listen and be sympathetic; to acknowledge the caller’s pain and make them feel, for a few minutes, not quite so alone.

Most suicidal people don’t make that call, though. They make up their minds and pursue suicide efficiently—just as Adams, Arbus and Woodman did. It’s hard to look at these women’s work now without sensing some of the pain they must have felt at the end of their lives. At least it’s comforting to know that they created unique bodies of work, finding release—however brief—through their photography.

——————–

FURTHER READING:

A 1994 article from the New York Times about writers and suicide. The author suggests that writers like Ernest Hemingway and Sylvia Plath liked the idea of suicide as a metaphor or grand flourish to end their lives; that it provided “a means of controlling their life story.”

This page has depictions of suicide in visual art through the ages.

This About.com page has a list of artists who committed suicide and how they did it.

3 comments on “ Clover Adams and Photographer Suicides ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Interesting.

Very interesting post Sarah. The area of suicide is such a difficult one to explore – knowing that a photographer committed suicide completely changes how you view their work.

PP: I agree. I think for some reason this is often even more the case with visual artists than with writers, though I’m not sure if I can articulate why. Diane Arbus’s suicide has become such an integral part of looking at her work, in a way that perhaps David Foster Wallace’s hasn’t.