Photographs Not Taken

A sentence can be rewritten, a painting repainted — but a photograph, once missed, can rarely be retaken. This evanescence, the delicacy of transient light, movement and atmosphere, gives photography its unique position in the arts. It’s what led Henri Cartier-Bresson to talk about the “decisive moment” when a photograph acquires the magic it didn’t have a split second earlier or later.

A sentence can be rewritten, a painting repainted — but a photograph, once missed, can rarely be retaken. This evanescence, the delicacy of transient light, movement and atmosphere, gives photography its unique position in the arts. It’s what led Henri Cartier-Bresson to talk about the “decisive moment” when a photograph acquires the magic it didn’t have a split second earlier or later.

Numerous photographers I’ve interviewed over the years have talked about the moments when, for various reasons, they didn’t take a photograph, so I was naturally excited to see the new book Photographs Not Taken , a collection of mini-essays edited by New York photographer Will Steacy . Sixty-two photographers—some famous, others up-and-coming—contributed to the book, and their reflections on the theme are appropriately diverse.

I met Steacy, and several of his contributors, at a signing event for the book recently at the

International Center for Photography.

The ICP was showing

Murder is My Business

, an entertaining and informative exhibit about Weegee, the 1930s-era murder scene photographer who, I’m pretty sure, had few scruples about clicking his shutter.

I met Steacy, and several of his contributors, at a signing event for the book recently at the

International Center for Photography.

The ICP was showing

Murder is My Business

, an entertaining and informative exhibit about Weegee, the 1930s-era murder scene photographer who, I’m pretty sure, had few scruples about clicking his shutter.

Steacy told me the theme of untaken photographs is something he’s thought about for many years. “As photographers, we all have endless inventories of what-ifs that haunt our conscious,” he said. “I often found myself at the bar trading these personal experiences with other photographers over beers, and I loved listening to my buddies’ stories.” Figuring that a book full of his own personal what-ifs would be “self-serving, one-dimensional and ultimately, boring,” Steacy decided to draw instead on his friends’ and mentors’ recollections.

I’m glad he did, because the essays in the book are remarkably varied and interesting. As critic Lyle Rexor writes in the introduction, there are many different reasons for not taking a photograph. They range from self-doubt to ethical dilemmas to being in the right place at the wrong time. Or you could simply be slow on the draw or forget to bring your camera.

Some of the more memorable essays in the book use words to summon up a strong visual image.

Todd Hido

writes about once seeing his mother “wearing her torn nightgown and a single sock, posing suggestively for my father.” (The snapshot his father took survives and has informed Hido’s own aesthetic.)

Elinor Carucci

, famous for raw images of her family, writes about seeing her twins: “Emanuelle naked holding tight to me in the bathtub. Eden bleeding in the emergency room.” These are pictures she hasn’t made because “the photographer declared war on the mother,” her protective instinct winning out.

Some of the more memorable essays in the book use words to summon up a strong visual image.

Todd Hido

writes about once seeing his mother “wearing her torn nightgown and a single sock, posing suggestively for my father.” (The snapshot his father took survives and has informed Hido’s own aesthetic.)

Elinor Carucci

, famous for raw images of her family, writes about seeing her twins: “Emanuelle naked holding tight to me in the bathtub. Eden bleeding in the emergency room.” These are pictures she hasn’t made because “the photographer declared war on the mother,” her protective instinct winning out.

In the “right place at the wrong time” category are Mary Ellen Mark and Lisa Kereszi , who both write that they regret not documenting their adolescence. “Those were such visual years,” Mark writes mournfully. Kereszi, who grew up in a colorful blue-collar neighborhood, regrets focusing inward rather than outward as a young girl, endlessly posing her Barbie dolls and “photographing my fantasies and not my real life,” she writes. Making up for lost time, she now has a book upcoming about her family’s junk yard business , she told me.

Of course, those are mature reflections—it might be hard to photograph one’s adolescence while caught up in its roiling emotions. Still, Mark writes that when she teaches high school students, she urges them to photograph their lives, feeling “it’s something that they’ll surely thank me for later in life.”

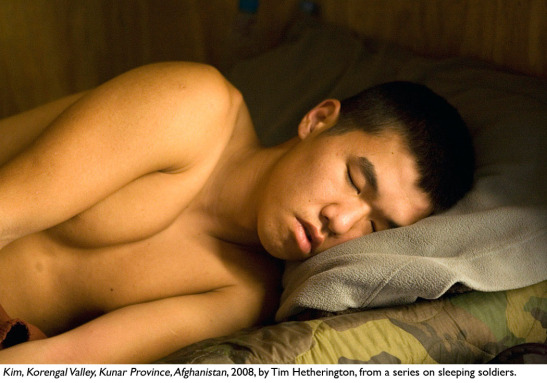

On the flip side of those luminous missed opportunities are the disturbing ones, the images not taken out of a sense of moral duty. Ed Kashi , coming across a horrific road accident in Pakistan, decided “to be there as a human being, not as an observer/documenter.” Similarly, Tim Hetherington writes about a road accident in Liberia that he didn’t photograph, honestly admitting that he was simply too exhausted, “my brain… like a plate of scrambled eggs.” Hetherington, of course, was killed last April in Libya, becoming one of the conflict victims that he was previously conflicted about photographing. An exhibition of his work (including the image below of a sleeping soldier in Afghanistan) goes on display at the Yossi Milo Gallery on April 12th for a month.

There’s plenty more in the book, too, including Sylvia Plachy ’s moving memory of seeing a large, dust-covered man walking robotically uptown on 9/11, and being unable to photograph him. “Diane Arbus would have done it,” she remarks ruefully. And Thomas Bangsted writes compellingly about an eerie scene he came upon in Denmark, a dead cow with a gas-bloated belly, its calf moaning nearby and a cat slinking by with a rat hanging from its mouth. “The sight was like a picture postcard that had taken a wrong turn—a case in point of dread in near-perfect equilibrium with the banality of bright daylight,” he writes. In this case, Bangsted didn’t actively decide not to take a photograph—he’d left his camera behind, he told me—but the scene remained etched in his memory, his evocation of it an example of Steacy’s belief that “a photograph can exist in words.”

As I said, these are varied, thought-provoking responses. Ultimately, says Steacy, this is a book not just about photography but about living, and the spontaneous decisions we all make on a daily basis. “It is my hope that the experiences described in this book will provide the catalyst for each reader to recall and dive into their own photograph not taken,” he wrote to me in an email. “We all have one. When you boil it all down, the stories in this book aren’t as much about photography as they are about being alive and being human.”

For the next post I’ll delve into my own archives and present thoughts by other photographers on the images they didn’t take.

2 comments on “ Photographs Not Taken ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Another wonderful post, Sarah.

But for me, the question of photographs not taken by conscious decision is less interesting – and less important – than the question of photographs missed because of being unprepared. All photographers are constantly making choices about how and whether to make an image. Each time we raise the viewfinder to our eye, and decide to shoot one thing rather than another, or to frame an image one way, and not another, we are deciding to not take a particular photo. But these alternative images weren’t lost, they were discarded; we decided, for one reason, or a host of reasons, that they did not encompass what we wanted to preserve.

On the other hand, images missed, wonderful, once-in-a-life-time images that were wanted to record but were unable to, are another matter entirely; they are the stuff of ‘what ifs,’ of life-long regrets. They are the photographic equivalent of sport fisherman’s ‘one that got away.

In order to stress the importance of being photographically prepared, of always carrying a camera, I give my students an exercise I call notebook. It requires that they go out for a few hours without a camera of any kind, and instead carry a small notebook. When they see an image they really want to make, they are to “shoot” it with the notebook, describing every detail they can about the scene, writing down how they would frame it, what lens and f stop they’d use, how they’d work the light; everything. They are to “take” about a half-dozen such images, come to class with them, and describe in detail their two favorites. The entire class discusses the images, and when it’s all over I stress that they will never, ever be able to capture that moment they miss; it is gone forever. All because they weren’t carrying a camera.

That sounds like a great exercise, B.D.! In addition to emphasizing the importance of carrying one’s camera everywhere, I like that it teaches the students to translate images into words. I think that’s a good practice for a photographer to develop (pun intended) as there may be times when only a combination of images and words can tell the whole story, or words may even be more appropriate.