John Isaac’s untaken photographs

Last week’s post

about the new book

Photographs Not Taken

made me think about my good friend John Isaac, retired head of photography at the United Nations. John often talks about the times when, for various reasons, he decided to put down his camera. He regards those decisions as an organic part of what he does, a piece of the complex mosaic that makes up his life as a photojournalist.

Last week’s post

about the new book

Photographs Not Taken

made me think about my good friend John Isaac, retired head of photography at the United Nations. John often talks about the times when, for various reasons, he decided to put down his camera. He regards those decisions as an organic part of what he does, a piece of the complex mosaic that makes up his life as a photojournalist.

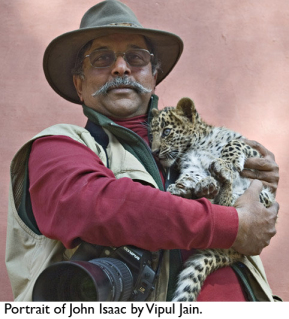

In addition to being a crack photographer, John is a charismatic guy with a wonderful history. He grew up in Irungalur, a non-electrified village near Trichy in India’s Tamil Nadu province. Music was an early passion and in 1965 he arrived in New York with Elvis sideburns, a guitar and 75 cents in his pocket. A few weeks later he was playing for money on the street in Greenwich Village when a woman stopped, listened to his rich baritone, and asked him to join her choir at the United Nations. Strapped for cash, John saw an opportunity. “Do you think you could find me a job there?” he asked.

What followed was a distinguished three-decade career at the United Nations, as he traded his guitar for cameras (though he still plays a mean version of Johnny Cash’s ‘Folsom Prison Blues’), and worked his way up from the mailroom to head the photography department. There have also been some interesting side journeys—like the time Michael Jackson asked John to document slums in Brazil, leading to a close relationship and exclusive rights to photograph Jackson’s children.

What followed was a distinguished three-decade career at the United Nations, as he traded his guitar for cameras (though he still plays a mean version of Johnny Cash’s ‘Folsom Prison Blues’), and worked his way up from the mailroom to head the photography department. There have also been some interesting side journeys—like the time Michael Jackson asked John to document slums in Brazil, leading to a close relationship and exclusive rights to photograph Jackson’s children.

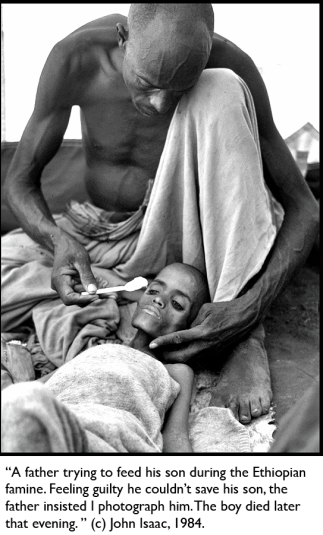

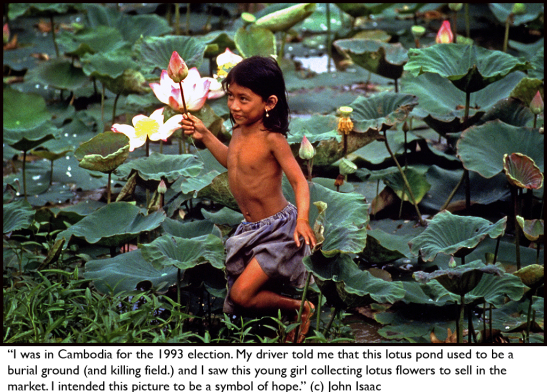

During his career with the U.N., John photographed in over 120 countries, documenting some of the most intense suffering of our times, from the 1983 Ethiopian famine to the 1994 Rwandan genocide. In the late 1990s, after photographing the aftermath of Rwanda and Bosnia, he suffered a nervous breakdown that led him to resign his position and almost give up photography. The chance sighting of a butterfly on a sunflower restored his sense of optimism, and since then he has focused largely on wildlife photography. He’s currently working on a book about India’s endangered tigers and wildlife.

Throughout his career, there have been many moments when John declined to take a photo. One of the earliest came in 1979, when he was on assignment in southern Thailand and came across a 13-year-old Vietnamese girl who’d been raped by pirates. “She was staring at the water, and wouldn’t look at anyone,” he recalls. Rather than raising his camera, John jumped in his Jeep, went to his hotel and picked up some chocolate and a tape recorder. “I’d taped some beautiful Vietnamese music and I sat next to her and played it. I held out the chocolate. After about 20 minutes, she took a piece.” Back in New York, he was laughed at by colleagues who told him he’d never succeed with such a soft heart—but he doesn’t regret his decision. “To me, it was worth more than all the pictures I could take.”

Soon after that experience, he traveled to a Malaysian island called Pulau Bidong to photograph Vietnamese boat people. After arriving, he was approached by a 10-year-old boy. “Are you like all the other journalists who spend days getting here, then stay for 15 minutes, ask us a few questions and leave?” the boy asked. “Do you think you can tell my story in 15 minutes?” Chastened, John immediately decided to stay for several days. “That was my first lesson in journalism, from a 10-year-old boy,” he says.

For John, powerful images are meaningless unless he feels he’s preserved his subjects’ dignity. In 1984, while at a feeding center in famine-ridden Ethiopia, he saw a woman who’d collapsed near a dilapidated building to give birth. The woman had passed out naked, the baby still attached to her. Knowing Ethiopians to be modest, John covered her up and ran to find medical aid. By the time he got back, a British television crew was hovering and the cameraman was ready to slug him. “He was pissed that I ruined this Pulitzer Prize-winning shot,” John says. His voice quivers as he remembers his mother’s advice: “Human dignity is more important than Pulitzer Prize-winning.”

For John, powerful images are meaningless unless he feels he’s preserved his subjects’ dignity. In 1984, while at a feeding center in famine-ridden Ethiopia, he saw a woman who’d collapsed near a dilapidated building to give birth. The woman had passed out naked, the baby still attached to her. Knowing Ethiopians to be modest, John covered her up and ran to find medical aid. By the time he got back, a British television crew was hovering and the cameraman was ready to slug him. “He was pissed that I ruined this Pulitzer Prize-winning shot,” John says. His voice quivers as he remembers his mother’s advice: “Human dignity is more important than Pulitzer Prize-winning.”

Of course, some would argue that the naked mother’s dignity is a price worth paying if it moves people to action—but John feels the trade-off is too damaging. “My basic philosophy is, whatever would hurt me would hurt someone else,” he says. “I look at the situation and think, I don’t think I’d like to be portrayed like this. I may be right and I may be wrong, but it’s my call and that’s what I’ve done.”

And then there are the times when he didn’t make a photograph of something joyful. In 1998 he was backstage at the War Child charity concert hosted by Luciano Pavarotti in Milan when he witnessed the first meeting of blind musicians Andrea Bocelli and Stevie Wonder. “I was riveted by everything they did, but I didn’t take a picture. I just wanted to enjoy the moment,” he says.

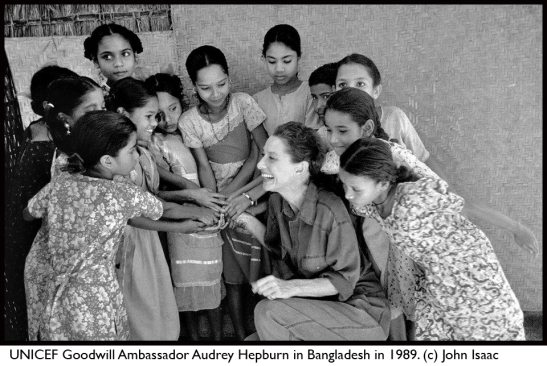

Similarly, he was traveling with UNICEF ambassador Audrey Hepburn in Ethiopia once when a young orphan girl ran to Hepburn and embraced her. The two started crying, at which point Hepburn’s boyfriend turned to John and asked why he wasn’t photographing. “I said, I don’t have to make a picture of everything. Let them just experience it,” he responded.

John credits Hepburn, along with Mother Teresa and his own mother, for helping him develop a healthy sense of balance. But a tipping point came in the late 1990s, when a little boy who’d survived the Rwandan genocide asked if John would adopt him. Heartsick, John gave the boy a toy car and explained that he couldn’t take that step. Soon after, he encountered a CNN cameraman excitedly photographing a pile of dead bodies, and something in him broke. That’s when he had his nervous breakdown. “I kept thinking about how I couldn’t help that boy,” he says.

These days, he brings his powers of observation to the animal world, photographing birds and tigers. He has also been conducting an ongoing love affair with the disputed region of Kashmir, resulting in the 2008 book

The Vale of Kashmir

. And he returns often to his native India, photographing everything from an epidemic of blindness in Bihar to a royal wedding in Rajasthan.

These days, he brings his powers of observation to the animal world, photographing birds and tigers. He has also been conducting an ongoing love affair with the disputed region of Kashmir, resulting in the 2008 book

The Vale of Kashmir

. And he returns often to his native India, photographing everything from an epidemic of blindness in Bihar to a royal wedding in Rajasthan.

Whenever he talks about his work, John leaves his audience moved and inspired. (I’ve witnessed this several times.) Technical skills are easy to learn, but integrity takes more effort and mastery. John’s career shows that you can have both and be better for it, even if you end up sacrificing some of those Pulitzer shots.

See more of John Isaac’s work at his web site .

27 comments on “ John Isaac’s untaken photographs ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

The story shows that there is more to being a photographer than having a good eye – John’s personality really comes through in the account, and the pictures have an awsome quality!

Thank you Angela Kane,

Looking forward to catching up with you soon.

John

Beautiful photographs…each tells a story

Thank you Ashu

To sacrifice money and fame in exchange for another human beings dignity and privacy is a very rare quality in a professional. My salaams to you John.

Dear Mallika,

Thank you for your note. Miss seeing you guys.

Johnny, we’re proud to have you as one of our oldest friends. Keep up the good work.

Dear John,

I have no idea to get your right email-address: Wishing you a happy birthday, lots of health and love! I’m often think about our great time together with MJ. It would be more than great to see you again.

Cheers,

Ralf.

Raif,

My e mail:

Please write to me.

John

I am so proud of our friendship as well. Imagine 50 years of friendship.

I owe a lot to America that welcomed me as an immigrant 42 years ago and to to the United Nations that helped me to become a photojournalist and sent me to so many countries and experience the news unfold. What is so nice about all of this is that I still shoot almost every day and travel and explore many new adventures at my age. My mother’s advice to me was never to loose the little curious boy that is within me. I thank her for all the good advice she gave me over the years. Sarah thank you for writing a such a positive account about my work.

Knowing John for many years, I can attest that he is one of the “good guys” in the photo business. Not only is he an excellent photographers, but an amazingly nice guy too!

Jeff, Thank for your comments. And thank you for your support and I am a proud Lexar Media man…

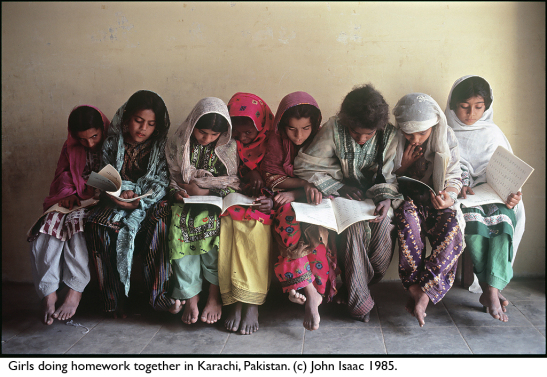

The stories were genuinely touching and the pictures of course speak for themselves. My favourite is the girls studying in Karachi, Pakistan. Hats off for the amazing work. Best wishes Neeti

Thank you Neeti,

I wish you the very best

in LIFE.

No need to tell you, beautiful, touching, ect…. photos.

You are one of the best today. But for me what is more importante is to have you for friend and to tell you that you are one of the best human beeing I never come across. Love you. Chantal

I think you’ve just captured the answer prfecetly

I hope so too..

Love you too Chantal. Next time in Mumbai, we will spend a day together. Thanks.

Diana Norris Beautiful and very touching at the same time. I loved the one of the girls looking at their schoolwork in Pakistan. The others tell a sad story but one we all need to know. .

Thank you Diana. I hope to see you soon.

Beautiful photographs John. They convey such compassion and capture the essence of the moment, each with its own story. I hope you visit the UK someday. Take care. Pamela

I will Pamela. I am going to have an exhibition at the Arts Club in London next year (2014). Will let you know

John,

I was struck by your story the first time I read it some years ago. I agree with you. Thanks.

Clint Whitmer

I recently met John on a trip to Graceland, where he took a photo of my daughter. I walked away after talking for some time thinking what an interesting man. I couldn’t wait to learn more about him. After reading this article, I now have to say he is an amazing human being and photographer. It was a pleasure meeting him.

Also, I feel honored that he photographed my child.

Thanks for your comment, Karen! You were lucky indeed to have a random encounter with John. He’s a special person!