Living with Books

“Are libraries obsolete now?” my husband asked a few months ago. We were staring up at the main branch of the

New York Public Library

—the magnificent Beaux-Arts building designed by Carrere & Hastings and opened in 1911—and I was outraged. I couldn’t conceive that anything as grand and beloved as this great institution could become obsolete, no matter how steadily

Google

,

Wikipedia

and

Amazon

are becoming our go-to sources of information.

“Are libraries obsolete now?” my husband asked a few months ago. We were staring up at the main branch of the

New York Public Library

—the magnificent Beaux-Arts building designed by Carrere & Hastings and opened in 1911—and I was outraged. I couldn’t conceive that anything as grand and beloved as this great institution could become obsolete, no matter how steadily

Google

,

Wikipedia

and

Amazon

are becoming our go-to sources of information.

Sure, there’s a ton of convenience associated with electronic information. I love the fact that I can tote around more than thirty books at a time on a single, lightweight device, and that I’ve been able to do a huge amount of research on my historical novel without leaving home. I love the feedback and reading communities that have emerged through social media, and that my son never has an excuse for not doing his homework. (Left your reading book at school? No problem! Here’s the e-book.)

But physical books have character! On my bookshelves at home, there are novels I’ve read so many times they’re like old friends; others I’ve reviewed professionally or have kept for sentimental reasons. There are art and photography books I might not open often, but that comfort me with their presence (and yes, also flatter my idea of myself as an arty person). These books are windows into my past. I like the way that collectively, they help me define an identity and reveal it to visitors. Needless to say, I also love browsing other people’s bookshelves and seeing how they’ve incorporated books into their lives.

The creators of

Living with Books

must have felt the same way. This French book, which has just been issued in paperback, looks at how a variety of people live with books. Photographer Roland Beaufre and journalist Dominique Dupuich scrutinized the collections of dozens of book lovers, from the hyper-organized libraries of rare book collectors to the more haphazard hoards of artists and writers.

The creators of

Living with Books

must have felt the same way. This French book, which has just been issued in paperback, looks at how a variety of people live with books. Photographer Roland Beaufre and journalist Dominique Dupuich scrutinized the collections of dozens of book lovers, from the hyper-organized libraries of rare book collectors to the more haphazard hoards of artists and writers.

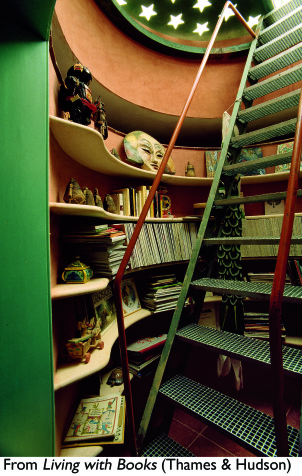

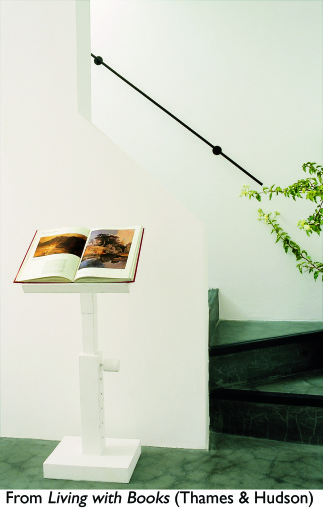

The book is organized into eight sections, mostly by occupation: designers, journalists, writers, artist. This is basically an interior design book, so everyone here is of a certain class—not just culturally elite, but also comfortable financially. Consequently, all of the interiors are rather upmarket and stylish, even the one owned by the bohemian painter who hangs out in Paris’s red light district.

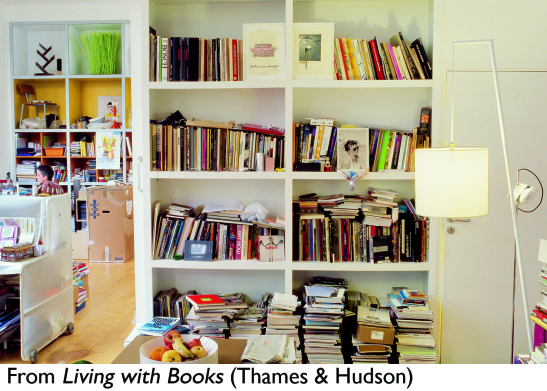

But along with their wealth, these people have an intense bibliophilia that, at times, jostles uneasily with their chic design aesthetic. Books add an element of disorder to any room. They slope to one side; they come in different sizes; they’re not color-coordinated. There’s something reassuring about this lack of uniformity; it speaks of human warmth and unpredictability.

And let’s face it, there’s an element of pretentiousness too. Which of us hasn’t wanted a potential friend or mate to look at our shelves and conclude—from the clustering-together of Lolita , White Teeth and Backlash —that we must be an unusually perceptive, intelligent and sensitive person? “My bookshelves were more successful with Veronica than my record collection,” says the narrator in Julian Barnes’ 2011 Booker Prize-winning novel The Sense of an Ending . “In those days, paperbacks came in their traditional liveries: orange Penguins for fiction, blue Pelicans for non-fiction. To have more blue than orange on your shelf was proof of seriousness.”

What will we do when these markers disappear? It’s hard to imagine a time when nobody displays books on their shelves—but then again, how many people do you know who still display their 33-rpm albums or even their CDs? Perhaps someone will soon devise a virtual bookshelf, similar to those electronic photo frames that cycle through different family pictures.

What will we do when these markers disappear? It’s hard to imagine a time when nobody displays books on their shelves—but then again, how many people do you know who still display their 33-rpm albums or even their CDs? Perhaps someone will soon devise a virtual bookshelf, similar to those electronic photo frames that cycle through different family pictures.

Given how quickly digitization is changing the publishing industry, the book Living with Books already seems a bit quaint. It’s like a dispatch from the 1980s, when Jay McInerney and Madonna were cutting-edge. There’s no discussion of how digital culture might be changing these readers’ habits or physical space. Indeed, although many of these photographs are of people’s workspaces, there’s hardly a laptop or a modem in view.

There is, however, proof of the enormous value people place on their books, and the central place they occupy, both physically and emotionally. “It can’t be denied that we love books,” Dupuich writes, and that we love them “with an obsessive passion that can transcend our social and professional environment.” So, books and libraries becoming obsolete? Not so fast. I, for one, intend to continue living with books for many decades to come.

FURTHER READING

This article by the President of the New York Public Library talks about how the library is changing with the times.

Salon.com’s Laura Miller writes about the NYPL’s innovative programming and why libraries still matter, here .

There is another book called Living with Books , written by the Prince of Wales’ librarian Alan Powers and published in 2003. It covers some of the same territory as the book discussed above, but looks to have richer (and wittier) textual content.

2 comments on “ Living with Books ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

What a timely post! I am remodeling my living room, and displaying some of my books is a huge priority for me. I think “really serious” readers take great pride in displaying their books. I’ll have a section of Booker Prize winners, a section dedicated to Margaret Atwood, and a section “other” favorites. I also considered streaming the book cover photos from my Kindle Fire on to the TV. My family vetoed that idea. I wonder what they would say if they knew I bought some books just to display them!

Great! I’m drooling looking at those images.

One thing I can see coming is that libraries (especially university libraries) will be under pressure to get rid of books – it’ll be presented as a wonderful high-tech cost saving. If every reader in the library has an e-book reader then you can fire a lot of staff, free up a lot of space which you can sell off or use for something else and just have an IT help line. It’ll be such a shame though. You just can’t browse ebooks in the same way. Nothing beats paper.