Rineke Dijkstra and the Solemn Portrait

Adolescence is a subject that has fascinated many photographers. That’s understandable: it’s a time that’s awkward, thrilling, beautiful and depressing—sometimes all at once. The raw material of childhood is being shaped by experience, but it hasn’t yet hardened into the rote patterns of adulthood. Capturing this complexity is a challenge that photographers as diverse as

Lauren Greenfield

, Jock Sturges and

Judith Joy Ross

have taken on.

Adolescence is a subject that has fascinated many photographers. That’s understandable: it’s a time that’s awkward, thrilling, beautiful and depressing—sometimes all at once. The raw material of childhood is being shaped by experience, but it hasn’t yet hardened into the rote patterns of adulthood. Capturing this complexity is a challenge that photographers as diverse as

Lauren Greenfield

, Jock Sturges and

Judith Joy Ross

have taken on.

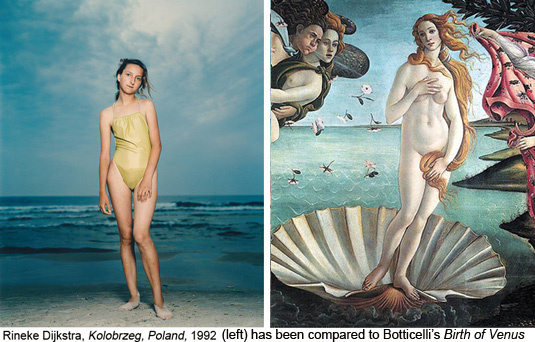

The Dutch photographer Rineke Dijkstra, whose mid-career retrospective is currently on show at the Guggenheim Museum New York , is also fascinated by the complexities of youth and adolescence. To be honest, when Dijkstra first burst onto the art photography scene in the early 1990s, I thought she was overrated. There was a lot of gushing about her portrait series of children and adolescents on beaches—with breathless comparisons between the image below and Botticelli’s Birth of Venus—but I found many of the portraits static and uninteresting. A few years later, I saw her series on bullfighters and new mothers at the Photographers Gallery in London. These portraits were fresher and more surprising, but I still found Dijkstra’s approach a bit clinical and academic for my taste.

Given this ambivalence, I thought it would be interesting to confront the full scope of her work at the Guggenheim. The exhibition is comprehensive, almost as large as last spring’s Cindy Sherman retrospective at MOMA . (Sherman is five years older than Dijkstra, but has very different preoccupations.) Few living photographers get this kind of treatment; the vast majority of museum photography shows are group surveys.

Like the territory of adolescence, my response to Dijkstra’s work at the Guggenheim was complex. I found some of the portraits gorgeous and affecting, while others seemed flat. Confusingly, this often happened within a single series. For example, take the two pictures below from the series Park Portraits . (Click on the image to make it larger.)

I loved the one at left, which—while certainly posed formally—captured something delicate and ineffable about first love. But the one at right seemed toneless and detached—and not just for the obvious reason that the girl is staring off-camera. In an interview with Anne-Celine Jaeger , Dijkstra said that a photograph “shouldn’t look forced, it should look like a snapshot. You’re not supposed to think it’s all set up. You should take it for granted and it should be totally natural somehow.” But her aesthetic—shooting from low angles, using fill flash and isolating subjects—gives her images a formality that is anything but natural.

Dijkstra’s park portraits are unusual in her work for including lush nature. Typically she isolates her subjects against a plain or white background, which is one distinct approach to portraiture. Other photographers—

Richard Avedon

,

Robert Mapplethorpe

,

Platon

—have used a similar approach to great effect. The idea, of course, is that by stripping away extraneous clutter and details you reveal something pure and true. Dijkstra has articulated this belief, stating that “if you show too much of a subject’s personal life, the viewer will immediately make assumptions. If you leave out the details, the viewer has to look for much subtler hints.”

Dijkstra’s park portraits are unusual in her work for including lush nature. Typically she isolates her subjects against a plain or white background, which is one distinct approach to portraiture. Other photographers—

Richard Avedon

,

Robert Mapplethorpe

,

Platon

—have used a similar approach to great effect. The idea, of course, is that by stripping away extraneous clutter and details you reveal something pure and true. Dijkstra has articulated this belief, stating that “if you show too much of a subject’s personal life, the viewer will immediately make assumptions. If you leave out the details, the viewer has to look for much subtler hints.”

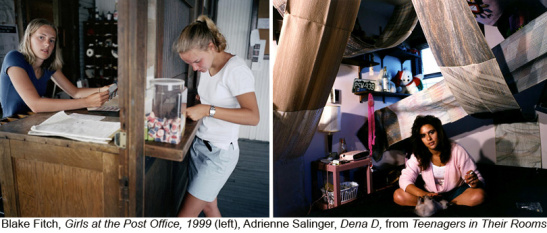

Fair enough. But I’d argue that photographers like Blake Fitch and Adrienne Salinger , who have photographed adolescents in their environments, have captured complexities and narratives just as demanding and subtle as Dijkstra’s. In her book In My Room , Salinger gained access to teenagers’ inner sanctums, places of intense self-expression. Fitch (whose show Expectations of Adolescence I wrote about here ) chose to follow two cousins growing into adulthood during lazy summers in upstate New York. In both cases, I think the ways the subjects interact with their environments are revealing.

I don’t want to argue that Dijkstra is a bad photographer, or somehow unworthy of a Guggenheim retrospective. I don’t think that’s the case. I like her focus on the awkwardness of reality, particularly as a corrective to the airbrushed images of perfect bodies that we’re bombarded with daily. And I appreciate her decision to use film where she feels a single image is too static. Five of her films are in the show, including a wonderful piece where a group of British schoolchildren respond to Picasso’s painting Weeping Woman . Their absorption and thoughtful responses are simply amazing.

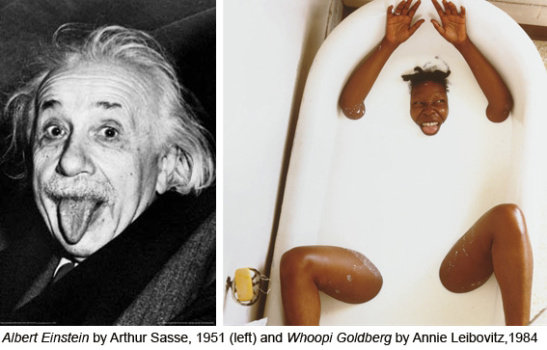

But one beef I have with Dijkstra, and certain other art photographers, is that she seems to feel that “serious” portraiture has to be minimalist and glum. Clearly this has to do with the church-state divide between amateur and professional photography, in which the prevailing wisdom is that smiling is for cheesy snapshots, whereas a true, insightful portrait requires the subject to look as if she’s contemplating Cicero or has a stomach ache. Sometimes this results in a wonderful portrait. At other times the thoughtfulness yields to a blank detachment. If a Martian came down to Earth and was asked—based on a walk-through of Chelsea galleries–to describe the human condition, I fear he’d report that we’re a solemn, humorless race.

But one beef I have with Dijkstra, and certain other art photographers, is that she seems to feel that “serious” portraiture has to be minimalist and glum. Clearly this has to do with the church-state divide between amateur and professional photography, in which the prevailing wisdom is that smiling is for cheesy snapshots, whereas a true, insightful portrait requires the subject to look as if she’s contemplating Cicero or has a stomach ache. Sometimes this results in a wonderful portrait. At other times the thoughtfulness yields to a blank detachment. If a Martian came down to Earth and was asked—based on a walk-through of Chelsea galleries–to describe the human condition, I fear he’d report that we’re a solemn, humorless race.

That seems like a missed opportunity. Serious portraits can be wonderful, but they’re not the only game in town. Consider, for example, the two surprising and delightful portraits below. They show that even cultural icons have multiple dimensions.

When I did my MFA degree in creative writing, my very first fiction workshop was led by the wonderful essayist Phillip Lopate . One thing Phillip said to us on the first day has stuck with me since. “It’s pretty easy to write stories where people are fighting and cursing and breaking up,” he said. “It would be great if some of you challenged yourselves to write a story about people getting along.”

By the same token, I’d like to challenge art photographers to take more great portraits of subjects showing the full range of their personalities.

———————————————————————————-

POSTSCRIPT:

After I published this post, there was a lively discussion about the lack of smiling in art photo-portraits on Erica McDonald’s excellent

DEVELOP Facebook page

. Erica and her readers posted some interesting links to articles by writers pondering the same issue, as follows:

Smile! A Polemic on Fine Art Portraiture and Portrait Photography, by Stephanie Dean

The Space Test , by Blake Andrews (whose blog Rumblings from the Photographic Hinterlands is well worth checking out)

A comment thread on the above post on another excellent blog, A Photo Editor .

An upcoming lecture on The Portrait in Contemporary Photography at the Guggenheim, October 2nd, 2012.

7 comments on “ Rineke Dijkstra and the Solemn Portrait ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Nice article Sarah..thanks.

John Isaac

Well stated, Sarah. Yout post has encouraged me to take more notice of the issues you talk about. I think it’s something we are well aware of in art photography but you articulate it in a way that brings the idea front and center. I look forward to seeing this exhibit and then having coffee together.

Thanks Amy and John! Amy, we’re racking up a few shows to visit together! I wouldn’t mind taking another look at this one (I was rushed last time) and also the London Street Photography exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York. Are you game?

I think about this smiling or lack there of issue a lot and it is something that kinda drives me crazy. I am working on a long term portrait project and my subjects smile a lot, I don’t direct them. In my editing critiques with friends and my MA classmates, the comments about too many people smiling is the most common. I have learned to edit, so that I show all ranges of emotion. But I love a great smile and I think it says a lot about humanity to let it show. I have had very similar issues with Dijkstra’s work myself. I will be releasing more of my project soon, currently working on the book. But you can see a small section on my website if you are interested. The project is called ‘Spinning Compass’, it documents travelers while on the road in ten cities all over the world. I am writing a paper at the moment about it and I am really glad I found your blog! Thanks for a well written review and the links to more articles about this topic in portraiture. Best, Linka

Linka, thanks for reading! Your portraits show a lovely ability to connect with people across cultures and make them feel comfortable and happy: I don’t think you should lose that, whatever people in your MA class say. I also love the questions you pose to travelers, especially “What are you carrying with you that has no practical purpose?” and “Is there a spiritual element to your journey?” It may sound trite, but I’d say that by expressing your own personality and doing what feels right to you, you’re likely to produce the strongest work. Good luck with your project!

Thanks Sarah, the project has been so much fun to work on. You wouldn’t believe some of the things people say on the questionnaires. I have shot in 7 countries/cities now & I have 3 more to complete the project. I am def not changing a thing. Again, thanks for checking it out and best to you!

Wonderful article, you have so rightly talked about the issues in portraits. A portrait should give some idea at least about the person being photographed and that should not always result in glum photographs