Gordon Parks: Picturing the Invisible

Gordon Parks, who was born a hundred years ago, was the very definition of a Renaissance man. Though remembered primarily as a photographer, he was a prolific writer, composer and movie director. He was also a pioneer. In 1948, he broke through racial barriers to become the first African-American to work at

Life

magazine. In 1969, he was the first black man to direct a Hollywood movie—an adaptation of his own novel

The Learning Tree

. As if that wasn’t enough, he composed the score for the movie, and went on to write several more books and direct

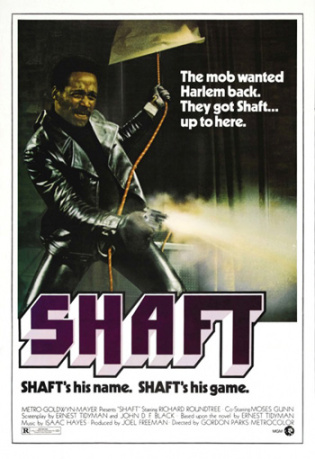

Shaft

, the first movie to feature an African-American detective.

Gordon Parks, who was born a hundred years ago, was the very definition of a Renaissance man. Though remembered primarily as a photographer, he was a prolific writer, composer and movie director. He was also a pioneer. In 1948, he broke through racial barriers to become the first African-American to work at

Life

magazine. In 1969, he was the first black man to direct a Hollywood movie—an adaptation of his own novel

The Learning Tree

. As if that wasn’t enough, he composed the score for the movie, and went on to write several more books and direct

Shaft

, the first movie to feature an African-American detective.

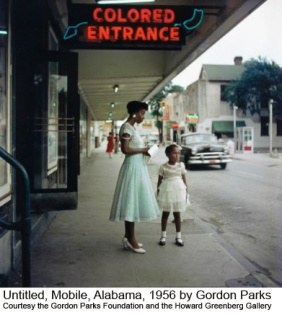

It’s fitting, then, that Parks—who died in 2006 at the age of 93, after a full and exciting life—is the subject of centennial celebrations all over town this fall. Exhibitions include Gordon Parks: 100 Moments at the Schomberg Center for Black Research , Gordon Parks: 100 Years , a public art installation at the International Center for Photography, and a twofer at the Howard Greenberg Gallery : Gordon Parks: Centennial and Contact: Gordon Parks, Ralph Ellison and ‘Invisible Man.’

I knew of Parks and had seen some of his “greatest hits” images, but it’s been a pleasure to learn more about him through these exhibitions. By any measure, he was an extraordinary man. Born dirt poor in Kansas, he lost his mother at 14 and spent many of his teen years homeless, eking out a living by playing piano in a bordello. After dropping out of high school he worked as a floor-mopper, a hotel busboy and a train porter, but always believed he was meant for more. “I suffered evils, but without allowing them to rob me of the freedom to expand,” he once wrote.

I knew of Parks and had seen some of his “greatest hits” images, but it’s been a pleasure to learn more about him through these exhibitions. By any measure, he was an extraordinary man. Born dirt poor in Kansas, he lost his mother at 14 and spent many of his teen years homeless, eking out a living by playing piano in a bordello. After dropping out of high school he worked as a floor-mopper, a hotel busboy and a train porter, but always believed he was meant for more. “I suffered evils, but without allowing them to rob me of the freedom to expand,” he once wrote.

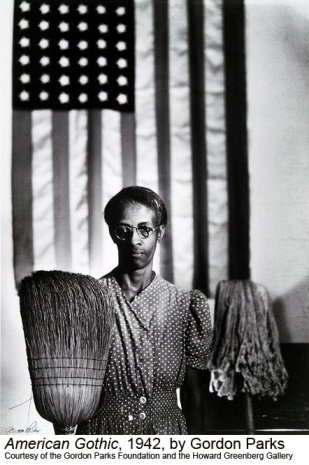

And expand he did. He dreamed big, not deterred by skin color. In 1941, a prestigious fellowship took him to Washington, D.C., where he worked for Roy Stryker’s Farm Security Administration Photography program. On his first day in D.C., Parks was barred from entering several buildings because of his race. Disgusted, he shot back by taking the powerful image American Gothic , in which a poor black cleaning woman represents the shabby treatment of blacks in America.

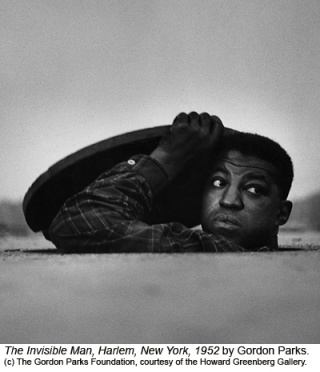

It’s no wonder, then, that Parks became friends with the writer Ralph Ellison. Like Parks, Ellison had grown up poor in the South and had worked as a professional musician. And like Parks, Ellison felt angered by the racism he observed around him. His anger led him to write the groundbreaking 1952 novel

Invisible Man

,

depicting the rage and frustration of a black man who feels invisible. Parks, who was working for

Life

magazine when the novel was published, was assigned to represent its world visually for a feature in the magazine.

It’s no wonder, then, that Parks became friends with the writer Ralph Ellison. Like Parks, Ellison had grown up poor in the South and had worked as a professional musician. And like Parks, Ellison felt angered by the racism he observed around him. His anger led him to write the groundbreaking 1952 novel

Invisible Man

,

depicting the rage and frustration of a black man who feels invisible. Parks, who was working for

Life

magazine when the novel was published, was assigned to represent its world visually for a feature in the magazine.

How do you depict an invisible man? Contact: Gordon Parks, Ralph Ellison and ‘Invisible Man’ at the Howard Greenberg Gallery, examines this interesting collaboration. It’s not clear how the assignment came about: Parks and Ellison had collaborated before, so it’s possible Parks suggested the piece. But I rather have the idea that a Life editor dreamed it up, as the combination of the season’s hot young black writer and the black staff photographer was too good to resist.

In any case, Parks took the brief and ran with it. As curator Glenn Ligon notes, there’s a tension in the series between the wish “to illustrate a fiction and to document a reality.” Parks had already shot extensively in Harlem, and he used some of these images–a tired man slumping by a street cart, a neat row of used shoes left out on the sidewalk–to add to the series. But he also went out of his way to reconstruct scenes from the novel. Contact sheets included in the show reveal how Parks staged several images, including the seemingly spontaneous title shot of a wild-eyed man poking his head out of a manhole.

In any case, Parks took the brief and ran with it. As curator Glenn Ligon notes, there’s a tension in the series between the wish “to illustrate a fiction and to document a reality.” Parks had already shot extensively in Harlem, and he used some of these images–a tired man slumping by a street cart, a neat row of used shoes left out on the sidewalk–to add to the series. But he also went out of his way to reconstruct scenes from the novel. Contact sheets included in the show reveal how Parks staged several images, including the seemingly spontaneous title shot of a wild-eyed man poking his head out of a manhole.

These images could easily have been trite or cheesy, but Parks’ visual fluency and thoughtfulness elevate them beyond mere illustration. Interestingly, the year Invisible Man was published was a high point in Parks’ own career. He’d just won a plum assignment to work in Paris for Life , and was leading a cosmopolitan life of glamor. During his celebrated career, he would photograph celebrities as diverse as Muhammed Ali, Malcom X and Ingrid Bergman. But he never lost his passion and empathy for Harlem, which shine bright and clear in his Invisible Man images.

The two shows at the Greenberg gallery make up a great combination. First, Gordon Parks: Centennial offers a broad overview of this extraordinary man and his career. Then Invisible Man zooms in on a single project, and we get a unique glimpse into Parks’ working methods. We see his love for Harlem, his feeling for its burdened residents. Somehow, he manages to make the invisible visible.

In 1952, Gordon Parks and Ralph Ellison were both at high points in their careers. Parks went on to grow creatively, working successfully in many artistic genres and retaining the courage of his convictions. (I love an anecdote about

Shaft

from a

Washington Post

article on display at the Schomberg Center. Richard Roundtree,

Shaft’s

star, had been told by studio executives to shave off his moustache because the image of a hairy-lipped black man was considered too macho. Passing Roundtree on the studio lot, Parks—himself possessed of a magnificent brush moustache–uttered five uncompromising words: “Don’t foul up the moustache.”)

In 1952, Gordon Parks and Ralph Ellison were both at high points in their careers. Parks went on to grow creatively, working successfully in many artistic genres and retaining the courage of his convictions. (I love an anecdote about

Shaft

from a

Washington Post

article on display at the Schomberg Center. Richard Roundtree,

Shaft’s

star, had been told by studio executives to shave off his moustache because the image of a hairy-lipped black man was considered too macho. Passing Roundtree on the studio lot, Parks—himself possessed of a magnificent brush moustache–uttered five uncompromising words: “Don’t foul up the moustache.”)

Ellison had a more tortured trajectory than his friend. After the stratospheric success of Invisible Man , he never published another novel, though he worked agonizingly on one for four decades. In 1958, he wrote to Saul Bellow that he had a “writer’s block as big as the Ritz.”

I don’t know enough about Ellison to speculate about what might have derailed his creativity. Seeing Parks’ work, though, and watching the documentaries about him playing at the Howard Greenberg Gallery and the Schomberg Center, what comes across is his enormous energy, passion and curiosity. He may not have been the easiest man to live with—in the documentaries, his daughter recalls being torn between admiration and longing for a largely absent father—but there’s no doubt about his polymath talent and drive.

A few years ago I interviewed the fashion photographer Matthew Jordan Smith , who photographed many black celebrities for his book Sepia Dreams: A Celebration of Black Achievement through Words and Images . Jordan Smith told me that after photographing Parks for the book he developed a warm relationship with the older photographer, who was a generous and encouraging mentor. I’ll end with Jordan Smith’s memory of visiting Parks a year before his death when, at 92, Parks was clearly still vigorous and productive:

“I knocked on the door and he opened it, grabbed my arm, pulled me in, saying, ‘You gotta see this!’ And he pulled me into his computer room to see his latest work. He was so excited, like a kid at Christmas! And I thought, Oh my god, I want to be like this, passionate and loving art my entire life. I see a lot of photographers who lose that feeling after a while. Gordon never did.”

“I knocked on the door and he opened it, grabbed my arm, pulled me in, saying, ‘You gotta see this!’ And he pulled me into his computer room to see his latest work. He was so excited, like a kid at Christmas! And I thought, Oh my god, I want to be like this, passionate and loving art my entire life. I see a lot of photographers who lose that feeling after a while. Gordon never did.”

—————————————————–

Several paragraphs in this essay appeared previously in Planet magazine online .

In addition to the exhibitions mentioned above, New York University exhibited Gordon Parks: Crossroads in September 2012.

Gordon Parks: A Harlem Family, 1967 will open at the Studio Museum of Harlem on November 8, 2012 and run until March 10, 2013.

2 comments on “ Gordon Parks: Picturing the Invisible ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Gordon Parks was an amazing man who persevered and realized his dreams despite society’s prejudices against him because of his skin color. An inspirational man who deserves the recognition he is getting. Thanks for writing about him Sarah!

Sarah, this is such a great story, and very timely for me:). The other day I was reading Anna a book (“My name is not Isabella”), and one of the characters is Rosa (with a reference to Rosa Parks), which lead to a discussion on civil rights (oh well, adjusted for age). Now your story on Gordon Parks is a great and very inspiring reading for me.:)