Fact versus Fiction in a Novel Package of Women Photographers

As I’ve mentioned before on this blog, I’m currently writing a historical novel with a photographic theme. So naturally, whenever a novel about photography is published (which seems to be increasingly often these days), my antennae go up. I’m always interested to see how novelists handle the challenge of writing about photography, with all its technical, emotional, ethical and aesthetic aspects. I know how tough it is to get those elements in balance in the context of a gripping story.

As I’ve mentioned before on this blog, I’m currently writing a historical novel with a photographic theme. So naturally, whenever a novel about photography is published (which seems to be increasingly often these days), my antennae go up. I’m always interested to see how novelists handle the challenge of writing about photography, with all its technical, emotional, ethical and aesthetic aspects. I know how tough it is to get those elements in balance in the context of a gripping story.

The latest novel to take on this challenge is the extremely ambitious Eight Girls Taking Pictures by Whitney Otto. (Thanks, Julie Brown, for bringing this book to my attention!) As its title implies, Eight Girls tells the stories of eight different female photographers, spanning roughly a hundred years from the 1890s to the 1990s.

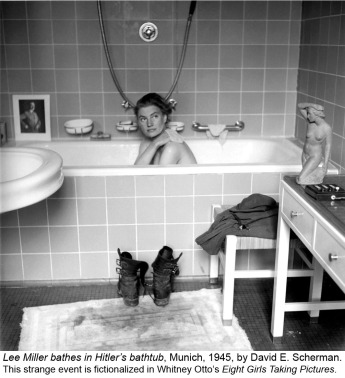

If you’ve ever wanted to get a feel for how women have contributed to photography without grappling with Naomi Rosenblum’s weighty A History of Women Photographers, this novel is definitely for you. Otto calls it “my love letter, my mash note, my valentine” to women photographers she’s loved throughout her life. They include Imogen Cunningham, Tina Modotti, Lee Miller and Ruth Orkin. Names have been changed (I’ll have more to say about that later), so Cunningham becomes Cymbeline Kelley, Miller is Lenny Van Pelt, Modotti is Clara Argento—and so on. In some cases, Otto tweaks their biographies too.

Of all the arts, women have arguably been allowed to contribute the most to photography. Reasons for this are many: they include photography’s emergence at a time when women were gaining independence, its hobbyist aspects (which allowed some women to begin at home as ‘dabblers’) and its initial status as a technical craft (which made it less threatening for women to be involved). Whatever the reasons, though, photography has long attracted the kind of strong, charismatic women who make for good fictional characters.

Of all the arts, women have arguably been allowed to contribute the most to photography. Reasons for this are many: they include photography’s emergence at a time when women were gaining independence, its hobbyist aspects (which allowed some women to begin at home as ‘dabblers’) and its initial status as a technical craft (which made it less threatening for women to be involved). Whatever the reasons, though, photography has long attracted the kind of strong, charismatic women who make for good fictional characters.

And sure enough, the women depicted in Eight Girls are all vibrant, unconventional characters. Each is a pioneer in her own way—whether she discovers a new technique or shows that children can be photographed unsentimentally. Each struggles to find her vision, but eventually manages to express herself transcendently through photography, with various personal costs.

The book unfolds chronologically, with each “girl” getting her own chapter. Otto focuses on how each woman struggles to maintain a balance between her art and her personal life. There are many challenges, which range from the inevitable -isms (sexism, conservatism, alcoholism, anti-semitism) to demanding husbands and children, wars, money problems and varying levels of self-doubt.

The book unfolds chronologically, with each “girl” getting her own chapter. Otto focuses on how each woman struggles to maintain a balance between her art and her personal life. There are many challenges, which range from the inevitable -isms (sexism, conservatism, alcoholism, anti-semitism) to demanding husbands and children, wars, money problems and varying levels of self-doubt.

Over time, some of these conflicts repeat themselves across generations and some ebb, only to have new ones seep in. Cymbeline Kelley marries a bohemian painter who urges her, “Let’s not be like anyone else,” only to find herself tethered to her children and the domestic sphere while her husband blithely leaves for months on end to pursue his art. Forty years later, Miri Marx (based on Ruth Orkin) is also expected to stay at home with her children, and thirty years after that, Jesse Berlin is struggling to define herself against an artist husband. Progress can be elusive. As the elderly Cymbeline says to the young Jesse (who’s photographing her for something called the BelleFemme project), “I sometimes think things are harder for young women now then they were in my time.”

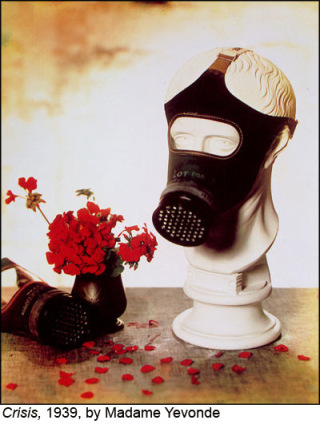

For me, one of the great pleasures of this novel was finding out about some amazing women photographers I didn’t already know about. For example, Madame Amadora, the subject of the second chapter, is based on the early twentieth-century British photographer Madame Yevonde. A literally colorful character, Yevonde pioneered the use of color photography in the 1930s, using the short-lived Vivex system. In her most famous series, The Goddesses, she photographed society women to look like goddesses from Greek and Roman mythology. The image at left shows how shockingly modern some of these images were.

For me, one of the great pleasures of this novel was finding out about some amazing women photographers I didn’t already know about. For example, Madame Amadora, the subject of the second chapter, is based on the early twentieth-century British photographer Madame Yevonde. A literally colorful character, Yevonde pioneered the use of color photography in the 1930s, using the short-lived Vivex system. In her most famous series, The Goddesses, she photographed society women to look like goddesses from Greek and Roman mythology. The image at left shows how shockingly modern some of these images were.

Charlotte Blum, who gets one of the best chapters, is another fascinating character. She’s based on Grete Stern, a German photographer who, along with her partner Ellen Auerbach, won prizes in the 1930s for striking avant-garde advertising images. Jewish in Weimar Germany, Stern and Auerbach worked together as Ringl + Pit, their childhood nicknames (thinking ‘Stern and Auerbach’ sounded too much like a department store) until the rise of Nazism forced them out. Stern later emigrated to Argentina, where she made a wonderfully surreal series of photomontages called Sueños (Dreams) to illustrate a women’s magazine column on psychoanalysis. (The image below is from the series.)

Otto writes about these characters with verve and lyricism, tracing the threads of influence and coincidence that connect them. I haven’t read fiction by her before, so I wasn’t quite sure what to expect. I saw the movie adaptation of her bestseller How to Make an American Quilt, and I remember thinking it was ok, if a bit sentimental. But I was impressed by her research, descriptions and characterizations here. For an author who straddles the divide between literary and popular fiction, she’s a pretty decent writer.

Otto writes about these characters with verve and lyricism, tracing the threads of influence and coincidence that connect them. I haven’t read fiction by her before, so I wasn’t quite sure what to expect. I saw the movie adaptation of her bestseller How to Make an American Quilt, and I remember thinking it was ok, if a bit sentimental. But I was impressed by her research, descriptions and characterizations here. For an author who straddles the divide between literary and popular fiction, she’s a pretty decent writer.

It’s all a lot to manage, though, and I have to confess that the eight stories and all their plots and minor characters got a bit overwhelming. Details got lost, and because all the chapters were written with the same blend of omniscience and close third person voice–not to mention the fact that many of the women had similar personalities–they often merged together. It didn’t help that I was reading this on a first-generation e-book reader that didn’t allow me to flip back and forth easily to refer to earlier sections. I would have liked it if Otto had worked a bit more to distinguish her eight protagonists from each other.

Compounding this difficulty was the fact that I was constantly in the process of comparing fact and fiction. Perhaps Otto thought that changing her heroines’ names would make it easier for readers to get caught up in their stories, but for me it was the opposite. Each chapter felt like a mystery: so who’s who here? I gave myself brownie points for every character I correctly identified: Morris Elliot is Edward Weston, Angel Andrs is Ansel Adams (not hard!), Tin Type is Man Ray, and so on. Confusingly, Otto isn’t consistent about her name-changing policy: Ansel Adams never appears directly but gets a name change, whereas Diego Rivera makes a cameo appearance as himself. And Lee Miller is mentioned in a late chapter, which is strange given that the earlier Lee Miller chapter casts her as Lenny Van Pelt.

Compounding this difficulty was the fact that I was constantly in the process of comparing fact and fiction. Perhaps Otto thought that changing her heroines’ names would make it easier for readers to get caught up in their stories, but for me it was the opposite. Each chapter felt like a mystery: so who’s who here? I gave myself brownie points for every character I correctly identified: Morris Elliot is Edward Weston, Angel Andrs is Ansel Adams (not hard!), Tin Type is Man Ray, and so on. Confusingly, Otto isn’t consistent about her name-changing policy: Ansel Adams never appears directly but gets a name change, whereas Diego Rivera makes a cameo appearance as himself. And Lee Miller is mentioned in a late chapter, which is strange given that the earlier Lee Miller chapter casts her as Lenny Van Pelt.

Admittedly, this might not be such an issue for readers who don’t know about these characters’ real-life analogs. I only knew about some of them, but even so, I found it a little distracting.

I could go on for a long time about the issue of changing names in historical fiction, because it’s something I’ve thought about a lot with my own novel. It’s a fraught issue. Historical novelists who don’t change real names open themselves up to easy criticism–but when novels keep the biography of a famous person intact and change the name, it can be annoying too. In the recent novel Waiting for Robert Capa (which I wrote about in a previous post), Spanish novelist Suzanna Fortes kept real names, and took some heat for sentimentalizing Capa and Gerda Taro’s relationship. But first-time novelist Gaynor Arnold faltered in her 2009 novel Girl in a Blue Dress, where she changed Charles Dickens into Alfred Gibson. I understand why she didn’t want to take on the mighty Dickens’ legacy, but the reinvention suffered by comparison–after all, who could hope to make up better names and characters than Uriah Heep, Abel Magwitch and Ebenezer Scrooge?

There are times when a novelist is only loosely inspired by a famous person. In that case, I think a name change makes sense. A case in point is one of my favorite photography-themed novels, Helen Humphreys’ luminous Afterimage. Humphreys was inspired by Julia Margaret Cameron, but changed Cameron’s life story significantly enough that the change of name to Isabelle Dashell seemed appropriate.

There are times when a novelist is only loosely inspired by a famous person. In that case, I think a name change makes sense. A case in point is one of my favorite photography-themed novels, Helen Humphreys’ luminous Afterimage. Humphreys was inspired by Julia Margaret Cameron, but changed Cameron’s life story significantly enough that the change of name to Isabelle Dashell seemed appropriate.

It’s a fraught issue, but in general, I’m for keeping real names wherever possible, because I think readers are sophisticated enough to know they’re reading fiction. The reason for fictionalizing a known person’s life is because you want to get inside that person’s head and present the inner life that accompanied their famous acts. Done well, that can be amazingly satisfying. It gives you a visceral sense of what it might have been like to be walking around in the skin of the character. If that’s not what you want, go read a biography.

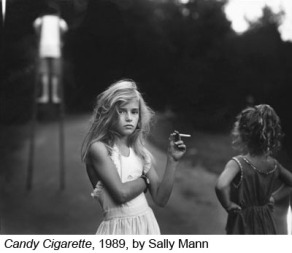

In Eight Girls Taking Pictures, Otto is caught in the middle. In the case of the two contemporary women characters (based loosely on Judy Dater and Sally Mann), I can see why she wouldn’t want to use real names. These women are alive, and it could seem indelicate to write about their intimate thoughts. Mann’s is probably the story Otto changes most: Jenny Lux’s images (and the controversy they cause) are clearly based on Mann, but the story takes place in California’s Napa Valley, a very different landscape from Mann’s native Virginia.

In Eight Girls Taking Pictures, Otto is caught in the middle. In the case of the two contemporary women characters (based loosely on Judy Dater and Sally Mann), I can see why she wouldn’t want to use real names. These women are alive, and it could seem indelicate to write about their intimate thoughts. Mann’s is probably the story Otto changes most: Jenny Lux’s images (and the controversy they cause) are clearly based on Mann, but the story takes place in California’s Napa Valley, a very different landscape from Mann’s native Virginia.

With the earlier women, though, Otto seems to have stuck very closely to the known biographies. Since her novel will be an introduction to the work of these women for many readers, I kind of wish she’d been able to use their real names. As I said above, with this volume of characters, working out who everyone was in the context of the novel was hard enough without playing the guessing game of who was whom in real life.

I don’t say this to discourage anyone from reading Eight Girls. The novel is based on eight fascinating women, and Otto has largely done them justice. Each chapter is absorbing and evocative. But be warned: take your time with the book, and make sure to read it in a format where it’s easy to flip back and forth. Then when you’re done—or while reading—go check out these women photographers’ wonderful images, starting with the resources below. That’s something you definitely won’t regret.

I don’t say this to discourage anyone from reading Eight Girls. The novel is based on eight fascinating women, and Otto has largely done them justice. Each chapter is absorbing and evocative. But be warned: take your time with the book, and make sure to read it in a format where it’s easy to flip back and forth. Then when you’re done—or while reading—go check out these women photographers’ wonderful images, starting with the resources below. That’s something you definitely won’t regret.

——————————————————————————————————————————–

RESOURCES

Madame Yevonde: An official site about Yevonde Cumbers Middleton (aka Madame Yevonde) with galleries of her images.

Lee Miller Archives: Official Lee Miller site.

This page shows many of Grete Stern’s surrealist Sueños (Dream) series.

Ringl + Pit is a documentary movie that tells the story of photographers Grete Stern and Ellen Auerbach.

Tina Modotti: A web site devoted to all things Tina Modotti.

Portraits of Women, 1964-2004, by Judy Dater (on whom the Jesse Berlin character is partly based)

13 comments on “Fact versus Fiction in a Novel Package of Women Photographers”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

This is a very insightful review that made me want to go on to read the book. I was particularly drawn into the debate on whether or not to use real names in historical fiction which leads on to a more general debate as to how true to the facts a writer of historical fiction has to be. Often readers of fiction (not necessarily historical fiction) will say not only how much they enjoyed a book but also that they learned something from it as well (say how to tie knots as in Proulx’s The Shipping News or about Thomas Cromwell in Wolf Hall). How do they feel then when they discover that what they learned was not true? I think the point that Sara makes here is a good one – if a novelist is only loosely inspired by a real person, then it makes sense to change the name. But if the novelist is trying to retain the general character/message/importance of the real person, then keep the real name.

Thanks, jdavidsimons! I sometimes feel that historical novelists can’t win: we’re damned if we do, damned if we don’t (in the case of name-changing). But that’s the glass-half-full! On the positive side, there’s so much to be gained from historical fiction — it is, as you say, a wonderfully immediate way of experiencing history. Curiously, I think filmmakers are given more latitude than novelists when it comes to historical fiction. Maybe because a film starring Leonardo diCaprio as J. Edgar Hoover or Ben Kingsley as Gandhi is so obviously a fiction?

In any case, I’m looking forward to reading your upcoming third novel An Exquisite Sense of What is Beautiful!

As soon as i began to read this novel, i was curious about the images. I began to look up each snd realized the names of the artists had been changed. So i began my quest and was fortunate enough to find your blog. Thank you for all the great links!

Glad you found the site, Annie! Hope you come back for more!

I’m reading Eight Girls Taking Pictures right now & enjoying it very much. Many

thanks for clearing up a lot of questions for me & giving me the resource list to find their photographs. Honestly, even though it was a novel based on these women, I think the author could have added more photographs! I found that more frustrating than the name changes.

Thanks, Janet! I think that including photographs was probably a rights issue: a lot of photographers and photographers’ estates charge hefty fees for reproduction. Also, maybe Otto felt shy about including too many images when she’d changed the names, or felt the images could be distracting. I appreciate your comment because I’m also writing a historical novel about photographers, and I will endeavor to get as many images in as possible. Thanks for reading!

Another thank you for your work. I’m reading Eight Girls Taking Pictures and wanted to view the work of the real artists. This helped immensely.

You’re welcome, Dianne! Glad to be of assistance!

I’m on the first story in Eight Girls and stopped to look up photos by “Cymbeline Kelley “. Happy to find your blog and info about the name changes. Will now explore the rest of the blog!

Thanks, Sally! I hope you enjoy the rest of Eight Girls! If you have time, drop a line when you’ve finished reading to say what you thought. I’m also writing a photography-themed historical novel and I’m very interested in people’s reactions to this genre!

Hi Sarah!

I wanted to thank you so much for writing about my novel, Eight Girls Taking Pictures. Someone handed me a copy of your blog last night and I thought that I may be able to answer a couple of questions.

1. The decisions not use the six photographers real names (and I really went back and forth on this point) was because the final two photographers were invented. In the Jessie Berlin chapter, Jessie takes a picture that looks like a Judy Dater picture but Jessie is NOT Judy Dater–not even loosely. I actually knew almost nothing about Judy Dater when I wrote the book. And Jessie’s experiences with feminism and consciousness raising groups were taken from my own life (though I am a bit younger than Ms. Dater).

Same thing with Sally Mann–I wanted to examine the photos of “Immediate Family” and the controversy and beauty of those pictures, without writing about Mann herself. I know next to nothing–well, pretty much completely nothing–about her life. I didn’t know enough about the lives of Mann or Dater to write about them; I only was inspired by some of their work. Because I used a mix of fact and fiction when building my characters, I needed a consistency with the names–I couldn’t call the final two photographers the names of known people when they had nothing to do with those people. But I would have gladly used the real names of the other six photographers if I could’ve.

And, yes, you were right–there were places where I used real name and when I didn’t. Sometimes it was okay to use real names and when it was I did it. I know that’s a kind inelegant reason, but there you have it.

2. The back of the book has an Author’s Note that names the real names of the six known photographers. The names are written in the first paragraph and in the order of their chapters so the reader can make the connection.

Additionally, I include a selected bibliography of their biographies, monographs, and autobiographical pieces with the note (again in the Author’s Note) telling readers that it would “be a mistake to skip their biographies and monographs” if at all interested in these women.

3. I make it clear that what I’ve written here is a portrait (an interpretation not unlike a photographic portrait, which would be different from photographer to photographer, even when the model remains the same), not fully realized biographies and I’ve talked about this in interviews and on line.

4. I would have LOVED to include tons of photographs but I was lucky to get to use eight of them–a couple of them were not my first choice because permissions/use issues have tightened up considerably over the years. You have a two part problem: The first is, you have to ask to use a picture, explaining how it will be used, and the rights holder can tell you yes or no–it is up to them. So I asked for certain photos and was told no, but I could pick another if I liked. It took me almost a year and THOUSANDS of dollars to secure those eight photographs. So, the money is the second part of the equation (as you can see).

5. Finally, with any book that draws from known people there is a whole legal aspect. That legal aspect can pretty much define what you can and cannot say–yes! Even in fiction. This is not a simple, quick process. But I could’ve used the names of the six known women, who are all deceased, had I opted to do so–but, as I explained before, that would leave me with the problem of the two fictional photographers.

6. I wrote this book for many reasons but one is that photography was a profession that included women almost from it’s inception and I was interested in (among many other things) what happens to a woman, in a given era, when you are in the profession (so you don’t have to break into it) but there are still womens’ issues. But this book is also about art, career, love, life.

7. I wrote a novel in the mid-1990s (published in 1997) called The Passion Dream Book that took inspiration for its two main characters photographers James VanDerZee (the famous Harlem Renaissance and beyond) and Madame Yevonde. This is my second photography novel.

I didn’t mean to go on for so long, but thank you again, Sarah, for taking the time to read and write so kindly about my book. It means a great deal to me. And best of luck with your photography book–I’ll be looking for it!

Wow, Whitney–thank you for checking in, and for taking the time to answer all these questions!

As you can see from the comments thread on this post, people have found my blog because they were looking up information about the photographers you portrayed so interestingly. I think it’s a testament to the strength of your narrative that people want to find out more, and I for one am grateful (as I said in the post) that you introduced me to some amazing photographers I hadn’t heard of before, like Madame Yevonde and Grete Stern. Now I really want to read ‘The Passion Dream Book,’ and will do so ASAP!

I’m really interested in the issue of legality when it comes to portraying real life characters in fiction. I’m just finishing a revision of my novel, which features two real photographers (both deceased). I’m keeping their real names, having gone back and forth on the issue. I assumed the publisher would just slap one of those ‘this is a work of fiction’ notices at the front, but is it more complicated than that?

Unfortunately, it can be more complicated, though it may not be in your case. A couple of the issues I had kind of blindsided me, actually. One rule of thumb is that you can’t libel the dead–so you’re pretty much free to say anything (as I understand it)–which means you may be okay with your novel as it reads now. The living is where you can have an issue or two (as you probably already know). The lawyer vetting my book may have been overly cautious–I don’t know–but I’m more than happy to tell you what I know about this process if you like–too much to write here. Feel free to email me if you like (www.whitneyotto.com) and I’ll send you my phone number–or send me yours and I can call you. But only if you want to.

I first saw Madame Yevonde’s work in 1990 when I was in London and they were mounting a show of her work. I had never heard of her and it was impossible to buy a book of her work here. I had my friend in London buy a copy for me, which I dog-earred. I loved her from the start.

With The Passion Dream Book, I did a slide show (yes, real slides in those days…) that accompanied the book (it as written up in Publisher’s Weekly because it was unusual for a novelist to give a slide show–but, what I discovered as I toured art schools (along with libraries and bookstores) that no one knew who she was. Even at some very large, well-known art schools. Twice I had slide librarians ask me about her and getting slides (which I had to have made myself, as they were unavailable anywhere–including England). She’s great, though. I’m glad you like her work.

I was introduced to Grete Stern’s Suenos when I was in Spain (around 1991). My Stern books are out of print (though I found a line on a few of the hardcovers of the Suenos for $150 -$175 out of Valencia–beautiful little book)–and found much the same response her as to M. Yevonde. However, MOMA just bought a print of “Electrical Appliances for the Home” last year.

Neither photographer is obscure–just not as well-known here–thought much better known since the Internet.

No hurry on reading The Passion Dream Book. Thats another story.

What is the title of your book? Again, please feel free to get in touch if you have questions.