Brilliance, Sex, Hubris: The Story of Polaroid

In his great wisdom, my ten-year-old son Nathan bought me a new photography-related book for Christmas. Never having been a big Polaroid fan, I probably wouldn’t have grabbed Christopher Bonanos’s

Instant: The Story of Polaroid

off the shelf myself. But once I started reading, I was quickly hooked. This is a story that has it all: dramatic reversals, hubris, sex, and an outsize leading man.

In his great wisdom, my ten-year-old son Nathan bought me a new photography-related book for Christmas. Never having been a big Polaroid fan, I probably wouldn’t have grabbed Christopher Bonanos’s

Instant: The Story of Polaroid

off the shelf myself. But once I started reading, I was quickly hooked. This is a story that has it all: dramatic reversals, hubris, sex, and an outsize leading man.

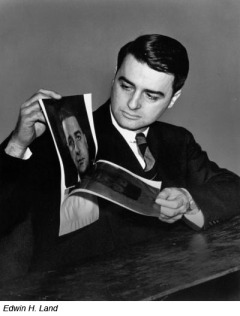

Bonanos traces Polaroid’s history from its non-photography beginnings (its polarizing filter was first applied to sunglasses) to its recent, humiliating rounds of bankruptcies and reinventions. Most of the story swirls around founder Edwin H. Land, a visionary who was pretty much the Steve Jobs of his time. In fact, Jobs acknowledged Land as his hero, traveling several times to meet the camera inventor in Boston. “The man is a national treasure,” Jobs told an interviewer in 1985.

Land was certainly an impressive person. A college dropout (like Jobs), he was clearly brilliant and extremely driven. His wife complained that he was always late; that’s because he was constantly working, not hesitating to call employees at 4 a.m. to discuss an idea. His mind was fast, dynamic and incredibly fertile. In 1970 he foresaw the smartphone, talking about “a camera that you would use as often as your pencil or your eyeglasses.”

Land was certainly an impressive person. A college dropout (like Jobs), he was clearly brilliant and extremely driven. His wife complained that he was always late; that’s because he was constantly working, not hesitating to call employees at 4 a.m. to discuss an idea. His mind was fast, dynamic and incredibly fertile. In 1970 he foresaw the smartphone, talking about “a camera that you would use as often as your pencil or your eyeglasses.”

There have been quite a few articles about how Jobs was inspired by Land. It may seem a stretch, but consider this: in the 1970s, photographers were shooting over a billion Polaroids a year. In its heyday, Polaroid specialized in creating products that were sleek, exciting, and, as Bonanos writes, “what people viscerally wanted.” And when Polaroids hit the market in the 1940s, there was usually a one-week wait between shooting photographs and seeing them, so that “the leap to Polaroid was like replacing a messenger on horseback with your first telephone.”

Consider, too, that Land was a genius at presentation. He might have believed that “marketing is what you do if your product is no good,” but he also intuitively understood the public’s need for image and theatrics. At Polaroid’s annual shareholders’ meetings, he often gave flashy presentations with slideshows and music. “A generation later, Jobs did the same thing, in a black turtleneck and jeans,” Bonanos writes.

Consider, too, that Land was a genius at presentation. He might have believed that “marketing is what you do if your product is no good,” but he also intuitively understood the public’s need for image and theatrics. At Polaroid’s annual shareholders’ meetings, he often gave flashy presentations with slideshows and music. “A generation later, Jobs did the same thing, in a black turtleneck and jeans,” Bonanos writes.

As for the product itself—Bonanos does a great job of explaining the mystique of the Polaroid image. “Seeing your own face emerge out of the misty goop has the quality of a sleight-of-hand or a striptease,” he writes, “a slow reveal, one that keeps you guessing, then delivers… It’s hard not to watch.” Anyone over thirty probably remembers the thrill of holding one of those white plastic squares, waiting for an image to swim up out of the green murk–which Polaroid’s advertising smartly likened to “opening a present.” Long before consumers expected instant gratification, Polaroid was dishing it out in giant spoonfuls.

Speaking of thrill, it didn’t take long for the public to realize another benefit of Polaroid: no lab technicians ever saw the image. “Instant photography’s success was at least in part built on adult fun,” Bonanos writes. Despite Polaroid’s carefully-honed image as an instrument of clean family entertainment, the company was well aware of its other uses. In 1965, Polaroid brought out a camera slyly called The Swinger. Small, pretty and fun, the camera practically winked at consumers. (In the 1980s, a series of successful Polaroid TV ads for the OneStep also featured James Garner and actress Mariette Hartley bantering sexily, as in the one below.)

Instant: The Story of Polaroid has other fascinating bits of Polaroid history. One of Land’s odder ideas was Polasound, a technology that would have allowed users to record photo captions with images (it failed). He employed an impressive number of women in senior positions, many of them Smith College graduates who brought an artistic sensibility to the company. And he prioritized research to an incredible degree, once giving an employee two years to simply observe and think about a problem.

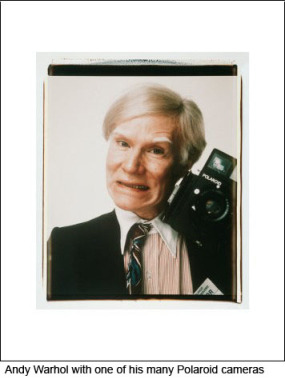

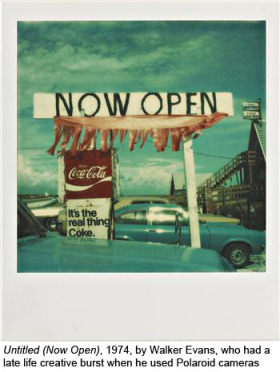

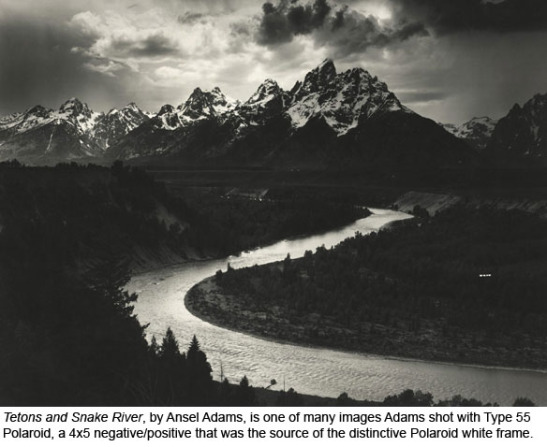

It’s also fun to revisit, in these pages, the work of artists who embraced Polaroid technology. Ansel Adams had a close, remunerative relationship with the company that lasted many decades. Walker Evans and André Kertesz both had late-career bursts of creativity thanks to Polaroid. Andy Warhol, Chuck Close, Robert Mapplethorpe and David Hockney all did distinctive work with Polaroids.

At the center of all this was Land, charismatic and handsome (in photographs here, he looks like Gregory Peck’s slightly less good-looking brother). Land was capable of soaringly persuasive rhetoric. Take this 1974 passage he wrote, extolling the virtues of the iconic Polaroid SX-70, which reminded me of Don Draper’s inspired pitch for the slide carousel in season one of Mad Men :

“It turns out that buried within us–God knows beneath how many pregenital and Freudian and Calvinistic strata–there is a latent interest in each other; there is tenderness, curiosity, excitement, affection, companionability and humor; it turns out, in this cold world where man grows distant from man, and even lovers can reach each other only briefly, that we have a yen for and a primordial competence for a quiet good-humored delight in each other; we have a prehistoric tribal competence for a non-physical, non-emotional, non-sexual satisfaction in being partners in the lonely exploration of a once-empty planet.”

Where did all this brilliance go? Well of course, Polaroid’s days as a market leader were numbered once digital photography gained hold, but that wasn’t the only factor in the company’s demise. Other elements included Land’s fallibility (he invested heavily in Polavision, a video recorder that was beaten out by Sony’s Betamax) and his failure to anoint a successor. After he was forced out, the company stumbled under different CEOs, each worse than the last. In 2008, CEO Tom Petters was arrested in an FBI sting and sent to prison for fifty years for stealing $3.65 billion from the company.

Where did all this brilliance go? Well of course, Polaroid’s days as a market leader were numbered once digital photography gained hold, but that wasn’t the only factor in the company’s demise. Other elements included Land’s fallibility (he invested heavily in Polavision, a video recorder that was beaten out by Sony’s Betamax) and his failure to anoint a successor. After he was forced out, the company stumbled under different CEOs, each worse than the last. In 2008, CEO Tom Petters was arrested in an FBI sting and sent to prison for fifty years for stealing $3.65 billion from the company.

It could have been different. Under a better CEO, Polaroid could have married its PoGo portable digital printer with a camera to produce a digital Polaroid (Bonanos spends several pages wondering why this didn’t happen). And if the CEO of the current, much depleted Polaroid, Bobby Sager–himself a photographer–had been in charge during the Petters years, Polaroid film would probably still be with us. Sager says here that he “wouldn’t have had the heart” to close it down.

Instead, Polaroid film is now a collector’s item, despite a huge outcry by fans. The energetic, failed attempt to save it shows the existence of a vibrant niche market: this market is now being partially served by T

he Impossible Project

, a boutique company of ex-Polaroid people. Another group,

the New55project

, is working on a replication of Type 55, and of course there are Hipstamatic, Instagram and all the other “retro” filter technologies that digitally replicate the look of Polaroids (I wondered why these weren’t mentioned in Bonanos’s book).

Instead, Polaroid film is now a collector’s item, despite a huge outcry by fans. The energetic, failed attempt to save it shows the existence of a vibrant niche market: this market is now being partially served by T

he Impossible Project

, a boutique company of ex-Polaroid people. Another group,

the New55project

, is working on a replication of Type 55, and of course there are Hipstamatic, Instagram and all the other “retro” filter technologies that digitally replicate the look of Polaroids (I wondered why these weren’t mentioned in Bonanos’s book).

“Why can’t I see the picture right away?” Posed by his three-year-old daughter, this question inspired Land to create the Polaroid. It was a vital link between roll film and digital photography, a great creative breakthrough. But the rise and fall of Polaroid is a cautionary tale. It shows that technical genius and vision aren’t always enough to ensure longevity. You also need to predict the future and align your vision with it–not just once, but time and time again.

————————————————————

A Literate Lens event! Join Sarah at the ICP Book Club, January 3rd 2013, 6:00 – 8:00 p.m.

Want to meet art and photography lovers who share your passion for novels? If so, please join me on January 3rd for the launch of the International Center for Photography’s Book Club! Each exhibition cycle, ICP will select a novel related to exhibition topics and host a meet-up for readers at the museum.

The current exhibition is Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life . On January 3rd at 6:00 p.m., ICP will host a walkthrough of the exhibition, following which I’ll be moderating a discussion of J.M. Coetzee’s powerful post-apartheid novel Disgrace .

Disgrace tells the story of David Lurie, a professor of Communications at Cape Technical University who loses his position after a ill-advised affair with a student. Disgraced, Lurie flees to the rural Eastern Cape community where his daughter Lucy has a small farm. When a shocking act of violence happens there, Lurie must grapple with his own sense of morality in a country caught in the chaotic aftermath of centuries of racial oppression.

The ICP is located at 1133 6th Avenue at 43rd Street. For more details, click here .

One comment on “ Brilliance, Sex, Hubris: The Story of Polaroid ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

LITTLE RED BUTTON!

(You missed a trick me thinks. Could have also explained how it terrified small, sensitive children.)

Nicola x M +44 (0) 7785 371 471 H +44 (0) 20 7435 2491