South Africa’s Disgrace in Words and Images

How do great literature and great photography enhance each other, and what can each do that the other can’t? Those of you who’ve been reading this blog for a while will recognize this question as an ongoing theme. Blame the specialized British school system of the 1980s, which didn’t allow me to study both visual art and literature at college. For years I bounced between the two, ending up—depending on whether you’re a glass half-empty or half-full person—either slightly schizophrenic or delightfully inter-disciplinary.

How do great literature and great photography enhance each other, and what can each do that the other can’t? Those of you who’ve been reading this blog for a while will recognize this question as an ongoing theme. Blame the specialized British school system of the 1980s, which didn’t allow me to study both visual art and literature at college. For years I bounced between the two, ending up—depending on whether you’re a glass half-empty or half-full person—either slightly schizophrenic or delightfully inter-disciplinary.

I was thrilled, then, when I was asked to guest-moderate the inaugural meeting of the International Center for Photography’s book club . Obviously, the concept is right up my street. For each exhibition cycle, the ICP chooses a book that underscores or amplifies the themes of the exhibit. Participants read the book, then attend an evening gallery tour and book club discussion.

The first book under the microscope was J.M. Coetzee’s powerful, unflinching post-apartheid novel Disgrace . It accompanied the exhibition Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life , which closed last weekend so unfortunately is no longer viewable. Of course, as in any conflict, photography played an important role in the struggle against apartheid, and the exhibition drew on a rich and exciting vein of material.

Anyone who lived through the 1980s will certainly remember the cruelty, violence and repression of the apartheid era. They’ll also remember the joy that erupted when Nelson Mandela was freed in 1990, and as the path to majority rule began. And then there was the inevitable reality-check: years of disappointment and conflict, punctuated by moments of genuine progress and uplift. To quote Donald Rumsfeld (not my usual go-to source), “democracy is messy.”

What you don’t always get as a distant observer of this struggle, though, is a sense of grey tones, the nuances that get lost in a time of raging conflict. Rise and Fall of Apartheid did a wonderful job of painting a full-tone picture of South Africa. There were the expected images of struggle—Ian Berry’s shocking documentation of the 1960 Sharpville Massacre, Joao Silva’s images from Soweto—but there were also photographs that illuminated quieter moments of everyday life.

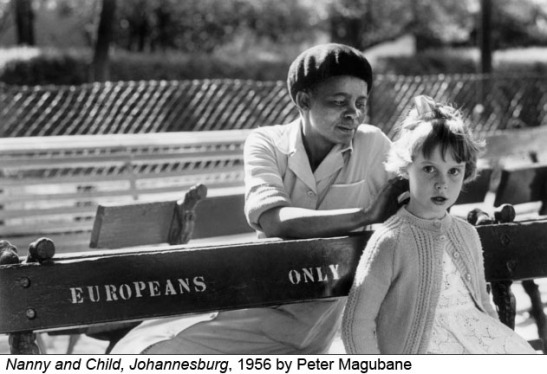

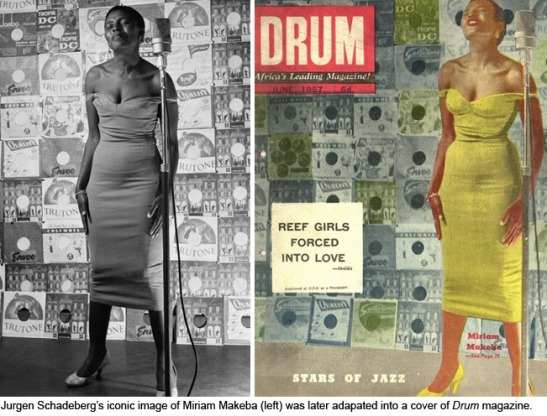

Take the lovely image above by Peter Magubane, of a nanny and child in 1956 Johannesburg, which shows that love can’t be segregated. Or this one, by Jurgen Schadeberg, of a protest by The Black Sash, an anti-apartheid group made up of respectable women from the suburbs. Another image by Schadeberg shows a terrifically sexy young Miriam Makeba in 1955, and was later adapted into a cover for

Drum,

a groundbreaking South African magazine.

Take the lovely image above by Peter Magubane, of a nanny and child in 1956 Johannesburg, which shows that love can’t be segregated. Or this one, by Jurgen Schadeberg, of a protest by The Black Sash, an anti-apartheid group made up of respectable women from the suburbs. Another image by Schadeberg shows a terrifically sexy young Miriam Makeba in 1955, and was later adapted into a cover for

Drum,

a groundbreaking South African magazine.

The exhibition ended with some more contemporary work, like Sue Williamson ‘s coruscating 1994 artist’s book A Tale of Two Cradocks . In this effective piece, the artist interposed pages from a bland guidebook of the Eastern Cape town Cradock with the story of Matthew Goniwe, a local resident who was pulled out of his car and shot to death by the police. Cleverly, the book was displayed like a concertina, so that viewers saw different stories depending on which side they stood—a potent metaphor for the effects of apartheid.

A novel could spend many pages painting a visual picture as strong and nuanced as some of these. But a novel can go places a photograph (or even a group of photographs) can’t: into a subject’s private reflections. For as much as we rely on documentary photography and photojournalism to bear witness to history, they’re mostly occurring in the public sphere. Some incidents, some transformations are beyond their reach—even, sometimes, beyond the reach of nonfiction. It takes a novelist to breathe life into them.

A novel could spend many pages painting a visual picture as strong and nuanced as some of these. But a novel can go places a photograph (or even a group of photographs) can’t: into a subject’s private reflections. For as much as we rely on documentary photography and photojournalism to bear witness to history, they’re mostly occurring in the public sphere. Some incidents, some transformations are beyond their reach—even, sometimes, beyond the reach of nonfiction. It takes a novelist to breathe life into them.

Coetzee’s

Disgrace

is a hugely ambitious novel, spare and precise in its language, but emotionally devastating. Set in the 1990s in Cape Town, it tells the story of David Lurie, a humanities professor who’s forced to resign when a student complains of sexual harrassment. Disgraced, David flees to the Eastern Cape, where his daughter Lucy owns a small farm. Thanks to changing land laws, Lucy’s former black employee Petrus has been able to buy land from her and their power relationship has shifted. When Lucy and David are brutally attacked by three black men on the farm, each character comes up with surprising and distressing responses.

Coetzee’s

Disgrace

is a hugely ambitious novel, spare and precise in its language, but emotionally devastating. Set in the 1990s in Cape Town, it tells the story of David Lurie, a humanities professor who’s forced to resign when a student complains of sexual harrassment. Disgraced, David flees to the Eastern Cape, where his daughter Lucy owns a small farm. Thanks to changing land laws, Lucy’s former black employee Petrus has been able to buy land from her and their power relationship has shifted. When Lucy and David are brutally attacked by three black men on the farm, each character comes up with surprising and distressing responses.

Disgrace has an interesting history. When it came out in 1999 it was widely hailed as a masterpiece outside South Africa. Inside the country, reactions were more mixed. Thabo Mbeki’s ANC government was particularly angry about the depiction of blacks in the novel, which it felt were stereotypical and one-sided, making blacks out to be largely violent and amoral. “South Africa is not only a country of rape,” Mbeki said.

In fact, when the Human Rights Commission convened in 2000 for hearings on racism, a government group denounced Coetzee as a purveyor of racist stereotypes–which presented an embarrassing dilemma for Mbeki three years later, when Coetzee was awarded the Nobel Prize. (In what one writer described as “

an ANC egg dance

,” congratulations were given and deemed not inconsistent with the censure.) Even fellow South African author and Nobel Prize winner Nadine Gordimer—usually a Coetzee admirer—weighed in, saying, “In the novel

Disgrace

there is not one black person who is a real human being.”

In fact, when the Human Rights Commission convened in 2000 for hearings on racism, a government group denounced Coetzee as a purveyor of racist stereotypes–which presented an embarrassing dilemma for Mbeki three years later, when Coetzee was awarded the Nobel Prize. (In what one writer described as “

an ANC egg dance

,” congratulations were given and deemed not inconsistent with the censure.) Even fellow South African author and Nobel Prize winner Nadine Gordimer—usually a Coetzee admirer—weighed in, saying, “In the novel

Disgrace

there is not one black person who is a real human being.”

(At the book club, someone asked if Nelson Mandela had congratulated Coetzee on his Nobel Prize. I didn’t know the answer, but later found this story , which reports that Mandela not only congratulated Coetzee but called him “an intellectual hero.”)

Gordimer’s comment brings up an interesting question, namely: is the student David has his affair with black or white? Coetzee leaves this ambiguous. Her name is Melanie Isaacs, which could be black but could also be Jewish. She’s attending college in Cape Town, which indicates that her family isn’t dirt-poor, but isn’t a marker for race: by the mid-1990s, there was open admission to college. David Lurie’s fictional Cape Technical University has black faculty members too.

Why does this matter? To my mind, Coetzee—an incredibly precise and purposeful writer—does this for a reason. He makes Melanie a blank screen to which readers bring their own preconceptions. In terms of the novel’s structure, it makes more sense if Melanie is black, and I think that’s the reason most critics have taken her race as a given. But Coetzee is a writer who doesn’t want anything to be easy (just read his later novels if you doubt that). The absence of a clear race markers for Melanie means we have to think carefully about how we perceive identities, make judgments and label people.

Why does this matter? To my mind, Coetzee—an incredibly precise and purposeful writer—does this for a reason. He makes Melanie a blank screen to which readers bring their own preconceptions. In terms of the novel’s structure, it makes more sense if Melanie is black, and I think that’s the reason most critics have taken her race as a given. But Coetzee is a writer who doesn’t want anything to be easy (just read his later novels if you doubt that). The absence of a clear race markers for Melanie means we have to think carefully about how we perceive identities, make judgments and label people.

And this, too, is something a photograph can’t do. It can’t strip away obvious visual information. Miriam Makeba is in front of us, gloriously vibrant, in a way Melanie Isaacs isn’t. Conversely, the characters in a novel have what might be described as a breathing presence, which is to say that we observe them over time, not in one static moment (or a series of static moments). We’re privy to their thoughts; we walk in their skin in a way that isn’t so possible with photographs.

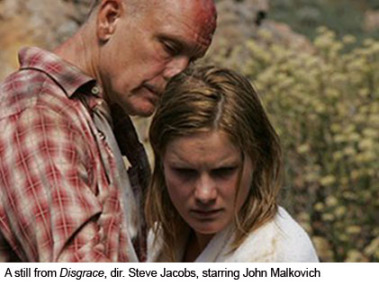

So it seemed somehow reductive, to me, when I watched the film adaptation of

Disgrace

. The film was stark, well-acted, difficult to watch—I can’t imagine it being a better adaptation, but it seemed flat to me after the novel. The ambiguities and doubts were mostly ironed out, the directors of course being obliged to translate Coetzee’s ellipses into tangible imagery. (In case you’re wondering, Melanie Isaacs is portrayed as a very light-skinned black woman.)

So it seemed somehow reductive, to me, when I watched the film adaptation of

Disgrace

. The film was stark, well-acted, difficult to watch—I can’t imagine it being a better adaptation, but it seemed flat to me after the novel. The ambiguities and doubts were mostly ironed out, the directors of course being obliged to translate Coetzee’s ellipses into tangible imagery. (In case you’re wondering, Melanie Isaacs is portrayed as a very light-skinned black woman.)

Calling Coetzee a purveyor of racist stereotypes is clearly beside the point. Though the novel exists on one plane as a piece of dramatic realism, it’s also rife with symbolism, becoming something of a racial political fable. Coetzee’s questions go much more than skin-deep (and skin-color-deep), into areas that affect us all: moral responsibility, accountability, humanism. Maybe the failure of the South African government to grasp this is what made the author emigrate to Australia in 2002.

I’m now reading a magnificent book on South Africa by Rian Malan, My Traitor’s Heart . It’s a nonfiction book by a white South African whose relatives played key roles in the apartheid era. Malan, who grew up instinctively liberal—alienated from his white family but not completely accepted by his black friends—does a wonderful job of describing his journey against a backdrop of turmoil. Like Disgrace , My Traitor’s Heart is full of moral conundrums and descriptions of brutal violence. But it also resonates with warmth, a quality that stands in counterpoint to Coetzee’s sometimes bleak vision.

———————————-

The next ICP Book Club pick is George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia , to accompany the exhibition We Went Back: Photographs from Europe 1933-1956 by Chim. Watch this space for details on the date.

———————————-

P.S. The Literate Lens turned a year old last Saturday! In its year online, the blog has garnered 188 subscribers, 39,400 page views, 140 comments and 198 Facebook fans. Thanks for your interest and support, and please keep your comments coming!

8 comments on “ South Africa’s Disgrace in Words and Images ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Dear Sarah: You are an excellent writer – and reader. Another great post.

One of your biggest fans, with love.

Vera Coleman vrcoleman@btinternet.com

Another wonderful post, Sarah. It’s striking how much the Weinberg image – “We stand by our leaders,” evokes the Ernest Wither’s “I Am A Man” image from the 1968 Memphis garbage strike.

This is great. Excellent point about the photograph not being able to hide obvious visual information.

I was at the book club and it was a good discussion. Thanks for leading!

Thanks, all! B.D., thanks for making me aware of the Ernest Withers image, I actually hadn’t seen it before. Frank, thanks for reading! Which one were you?

I’m 22 so I think I was the youngest person there. I asked why the president would HAVE to congratulate Coetzee. I ate a lot of cookies! That one!

Ah yes, now I see your picture and remember you! But didn’t notice you gobbling cookies! Thanks again and good luck in all your endeavors.

Great article – enjoyed it a lot. This is fascinating stuff. A good photo-history book I came across recently about how South African photography responded to Apartheid is Defiant Images by Darren Newbury.

I think where literature excells is being able to communicate what goes on inside the character’s head which isn’t always obvious in a photograph.