Jack Kerouac, Middle-Aged Woman?

Imagine Jack Kerouac as a pretty, middle-aged woman. Can you do it? Is your brain boiling and steam coming out of your ears yet? Given Kerouac’s much-documented sexism and position as America’s beloved literary bad boy, the idea of hearing his words come out of a mature woman’s mouth might seem a stretch. But that’s exactly what you’ll experience if you head to the Center for Photography at Woodstock for Adie Russell’s unexpectedly charming exhibition,

I Am (Richard Nixon)

.

Imagine Jack Kerouac as a pretty, middle-aged woman. Can you do it? Is your brain boiling and steam coming out of your ears yet? Given Kerouac’s much-documented sexism and position as America’s beloved literary bad boy, the idea of hearing his words come out of a mature woman’s mouth might seem a stretch. But that’s exactly what you’ll experience if you head to the Center for Photography at Woodstock for Adie Russell’s unexpectedly charming exhibition,

I Am (Richard Nixon)

.

Russell, a multi-media artist, is a bit of a reverse Cindy Sherman. Rather than morphing into different female characters, she has chosen to remain happily herself while lip-synching to found audio of interviews with iconic men of the 1950s, 60s and 70s (in addition to Kerouac they include Marlon Brando, Ingmar Bergman and Richard Nixon). Their words literally come out of her mouth, or that’s the illusion, which is sustained remarkably effectively.

A loose theme running through all these interviews is the men’s search for identity and meaning, which makes it pretty ironic that they’ve been appropriated by this contemporary woman. Russell says she wants to bring together the historical and present moments, in order to create “a kind of third space where meanings shift, judgments waver, visual cues are displaced, and the language hovers, unattached to the identity of the original speaker, and yet not quite able to attach to my identity, my image, my mouth, my gestures.”

See if you think she succeeds by watching the video below:

It’s a neat trick, for sure, but is it more than that? Certainly, hearing Kerouac’s words mediated through Russell’s appearance did make me feel a bit more open to them and him, and less inclined to think of him as a self-involved jerk (or just a self-involved jerk). The guy had a poetic sensibility, and although “go moan for man, go moan, go groan, go groan alone, go roll your bones alone” may not represent the apotheosis of his talent, you have to admit it has rhythm and originality.

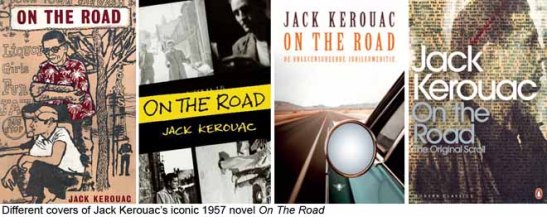

I say this as a confessed non-admirer of Kerouac. When I read On the Road twenty years ago, it didn’t do much for me. The macho, whiskey-swilling wanderlust and availability of hot, undemanding women seemed like the stuff of febrile male fantasy. In fact, Carlo Marx, the Allen Ginsberg character in OTR , describes Dean Moriarty as “a ‘child of the rainbow’ who bore his torment in his agonized priapus,” which pretty much says it all. Neeedless to say, the women characters who enjoy sex are not glorified like this.

Still, after seeing Russell’s uncanny lip-synching Kerouac video, I cracked open On the Road again. Would her performance, or the intervening years, have changed my perceptions?

Yes and no. There’s a run-on, hynoptic quality to Kerouac’s prose that makes it entertaining, even when it’s rambling and shapeless. And although it’s a ridiculously romantic vision of America, in which a young guy “tremendously excited with life” can hitch across the country without befalling anything worse than the loss of a flannel shirt, meeting happy drunks and sexually accommodating women along the way, there’s something joyful and alluring about the fantasy. It was the template for a new genre of road books, movies and hippie road trips to come.

But there’s a ridiculous double standard operating here. Dean is described in the most romantic terms, as “a western kinsman of the sun”—a transcendent quality that excuses all his moral lapses. But to Dean, the moment Marylou gets tired of “mak[ing] breakfast and sweep[ing] the floor” and goes back to Denver, she’s “the whore.” For women of the Beat Generation, it appears that being liberated meant playing domestic goddess to a creative, promiscuous drunk—progress indeed!

But there’s a ridiculous double standard operating here. Dean is described in the most romantic terms, as “a western kinsman of the sun”—a transcendent quality that excuses all his moral lapses. But to Dean, the moment Marylou gets tired of “mak[ing] breakfast and sweep[ing] the floor” and goes back to Denver, she’s “the whore.” For women of the Beat Generation, it appears that being liberated meant playing domestic goddess to a creative, promiscuous drunk—progress indeed!

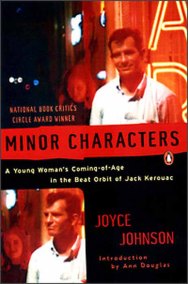

This irony is explored in Joyce Johnson’s wonderful memoir

Minor Characters

. Johnson writes about herself and other women who tried to ride along with the men of the Beat Generation, only to find themselves relegated to the sidelines. Johnson was Kerouac’s lover, on and off, for two years preceding and following the publication of

On The Road

. The story of their affair is the story of Kerouac’s multiple abandonments of her, punctuated by moments of joyous intensity that keep her hooked. But try as she might, Johnson is never admitted into the exclusive boys’ club. At one point, her older self reflects sadly that she was attracted to men who offered her “some pursuit of the heightened moment, intensity for its own sake, something they apparently find only when they’re with each other.”

This irony is explored in Joyce Johnson’s wonderful memoir

Minor Characters

. Johnson writes about herself and other women who tried to ride along with the men of the Beat Generation, only to find themselves relegated to the sidelines. Johnson was Kerouac’s lover, on and off, for two years preceding and following the publication of

On The Road

. The story of their affair is the story of Kerouac’s multiple abandonments of her, punctuated by moments of joyous intensity that keep her hooked. But try as she might, Johnson is never admitted into the exclusive boys’ club. At one point, her older self reflects sadly that she was attracted to men who offered her “some pursuit of the heightened moment, intensity for its own sake, something they apparently find only when they’re with each other.”

Johnson’s memoir contains many other “minor characters.” There’s Joan Vollmer, the brilliant and drug-addled wife of William S. Burroughs, who was fatally shot by her husband during a drunken game of William Tell. There are the young women in Johnson’s English class at Barnard College who are told by “grey-haired, craggy-faced” Professor X that “if you were going to be writers, you wouldn’t be enrolled in this class… you’d be hopping freight trains, riding through America.” But the most tragic story belongs to Elise Cowen, Johnson’s brilliant and doomed best friend, a voracious reader and generous soul who “couldn’t reconcile her intellectual passions with the need to get by through fulfilling requirements.” Hopelessly in love with Allen Ginsberg (they’re lovers before he opts only for men), Elise spirals downward after he leaves. She’s Johnson’s dark shadow, the embodiment of the danger lurking in a woman’s desire to be free.

Johnson (who recently published a biography of Kerouac ) was one of my first and best writing teachers in the Columbia MFA program. It’s been a while, but I remember her as a perceptive critic and a great booster of anyone she thought talented. In another irony, Minor Characters —her depiction of her minor status in the Beat Generation—ended up catapulting her to literary fame, while her novels have been largely overlooked. Minor Characters won the National Book Critics Circle award and has been widely celebrated as a lovely, eloquent evocation of that period in America’s cultural history.

To get another bead on Kerouac and

On the Road

, I watched the recent film adaptation of the novel. Helmed by Brazilian director Walter Salles, it’s a reasonably faithful adaptation that’s beautifully shot, giving rose-and-gold tones to everything from a Rocky Mountain sunset to a San Francisco jazz dive. Physically, the period detail is impeccable and makes for enjoyable watching, but something doesn’t gel about the movie. Possibly it’s the miscasting of the two male leads, whose performances are overshadowed by the charisma of Kristen Stewart and Kirsten Dunst as the “minor characters.” Or, as critic David Haglund writes in

a perceptive review on Slate.com

, “Maybe it’s just that the transgressions of the Beats don’t feel that transgressive anymore. Kerouac may have thrilled to ‘the enormous presence of whole great Mexico’ with its ‘billion tortillas frying and smoking in the night,’ but when, in the movie, Sal and Dean visit a brothel in Mexico City, the term

sex tourism

is hard to keep from your mind.”

To get another bead on Kerouac and

On the Road

, I watched the recent film adaptation of the novel. Helmed by Brazilian director Walter Salles, it’s a reasonably faithful adaptation that’s beautifully shot, giving rose-and-gold tones to everything from a Rocky Mountain sunset to a San Francisco jazz dive. Physically, the period detail is impeccable and makes for enjoyable watching, but something doesn’t gel about the movie. Possibly it’s the miscasting of the two male leads, whose performances are overshadowed by the charisma of Kristen Stewart and Kirsten Dunst as the “minor characters.” Or, as critic David Haglund writes in

a perceptive review on Slate.com

, “Maybe it’s just that the transgressions of the Beats don’t feel that transgressive anymore. Kerouac may have thrilled to ‘the enormous presence of whole great Mexico’ with its ‘billion tortillas frying and smoking in the night,’ but when, in the movie, Sal and Dean visit a brothel in Mexico City, the term

sex tourism

is hard to keep from your mind.”

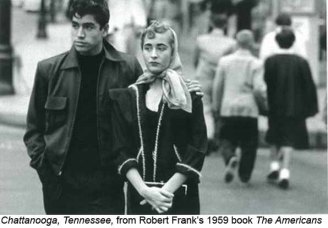

Watching the movie of On the Road makes it abundantly clear that Kerouac’s romanticism and sexual politics have dated as badly as the novel’s occasional whiffs of racism. But let’s give Kerouac his due. At its best, his work has a moody lyricism and ecstatic energy. He wrote a wonderful introduction to The Americans , Robert Frank’s seminal 1958 book about American dysphoria. Here, Kerouac’s musical, hypnotic prose is a perfect match for Frank’s intimate, elegiac images. In Kerouac’s words, Frank perfectly captured “that crazy feeling in America when the sun is hot on the streets and the music comes out of the jukebox or from a nearby funeral.” He “sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film, taking rank among the tragic poets of the world.”

Seeing Adie Russell speaking Kerouac’s words, I couldn’t help thinking that part of his tragedy, and that of the Beats in general, was that their vision of creative freedom didn’t extend to women. Instead, it was a curiously half-formed vision of liberation in which men’s self-actualization crashed up against a 1950s view of women as “sweet little girl”s and housewives. Something had to give, and it did: some of the men, and most of the women, died young and/or violently. Miraculously, Joyce Johnson survived to tell the tale.

————————————————————————-

FURTHER READING AND WATCHING:

Jack Kerouac being interviewed on the Steve Allen Show , including him reading the passage that Adie Russell lip-synched.

Adie Russell’s web site , where her videos of Nixon, Bergman and others can be viewed.

An essay in which Vince Passaro contrasts Kerouac’s romanticism with Joyce Johnson’s hard-edged realism.

An essay about women of the Beat Generation, on the site of a literary journal dedicated to the study of Beatdom.

I wrote about the 50th anniversary reissue of Frank’s The Americans here and here .

11 comments on “ Jack Kerouac, Middle-Aged Woman? ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

There are a lot of layers here – Jack Kerouac in his own era, Jack Kerouac through contemporary eyes, the historically-evocative work of Joyce Johnson and Walter Salles, and the recontextualizing by Adie Russell (which, as predicted, I’m having difficulty imagining!)

I’m fascinated by the idea of the inadvertent honesty that you sometimes get with contemporary writings. If Kerouac had been writing in the 1970s (whatever that might have meant), he might have been smart enough to disguise his sexism, even if it was still his essential self. But in the 1950s he left it open so, now, we can see it plainly. I find it easier to forgive something that at least isn’t being hidden.

I guess the real hope is that 1970s-Kerouac, newly made aware that his attitudes were sexist, would by the same token reject them and mend his ways. Would that take away his redeeming artistic value?

DAn.

Ha ha! Thanks for leading me to imagine a cleaned-up, politically-correct Kerouac. I guess in that case he’d also belong to AA, donate money to the NAACP and fight for immigration reform. And we probably wouldn’t want to read anything he wrote 😉

I do believe that the old image of the renegade, alcoholic author is outmoded, though. To take an example, Alice Munro seems to be able to write pretty well and I don’t think she’s knocking back six-packs and having torrid affairs in her spare time.

This makes me think of an anecdote (possibly apocryphal) about Dustin Hoffman working with Laurence Olivier on Marathon Man. Apparently Hoffman had been sleeping rough to get in character, and Olivier asked him why he was torturing himself. Hoffman asked what he should do instead, to which Olivier replied, “Try acting, dear boy.”

Yes, of course a cleaned-up Kerouac would be boring – as boring as Alice Monro and her like.

What an interesting piece Sarah! And how interesting to have a connection to Johnson. p.s. I just skimmed your comment re Marathon Man. Ironically, and on a complete aside, Hil and I had been extras in the movie (although I think we were ultimately cut from the film). Great article! 🙂

Actually, Oliver said, “Try acting, dear boy – it’s easier!”

Other women survived to tell the tale in poetry and prose, Diane Di Prima, Anne Waldman, Hettie Jones, Joanne Kyger, Janine Pommy Vega (who died only recently) and ruth weiss, were all female artists and dissidents. See Nancy M Grace and Ronna C. Johnson ‘Breaking The Rule of Cool: Interviewing and Reading Beat Women Writers’.

Thanks for this, Mary! I knew about Diane Di Prima and Hettie Jones but not the others.

Thank you for this lovely survey of many contrasting currents. As many young men do, I went through a phase where I venerated Kerouac and tried to follow in his footsteps (in my own way, of course). But in the early 1990s, it was hard to do this with the same feigned macho swagger, and indeed, I think I always saw Kerouac as more of a scared little boy (which resonated with me) who ended up giving in to his Catholic guilt (exacerbated by the disease of alcoholism, of course).

Around that time, his writing was also being reassessed, but I never quite bought it. I enjoyed some of his books, but I always felt that he was trying too hard to be a 50s version of Henry Miller (another complicated figure whose influence on the Beats is acknowledged far too rarely, for some reason).

Kerouac’s real power was more in the nature of his investigation. He attempted, ambitiously but mostly unsuccessfully, to tap directly into a jazz-like, ongoing, stream of consciousness and make it visible. This didn’t result in good “literature” for the most part, but when it worked, it sang with its own glorious cadence that is still capable of reaching me more than twenty years later. I also always admired how he wore his insecurities and demons (including his troubles with women) on his sleeve.

I’m neveretheless grateful that you’ve encapsulated some of the ways in which women were treated during that time. I’ll agree that much of what went down was reprehensible, and downright contradictory, considering that much of what the Beat movement was about was arguably to get in touch with feminine/yin energies in opposition to the dominant masculine/yang forces that ruled the day (via the rise of militarism, the reinforcement of patriarchy after the temporary lull in the 1940s, and so on). I’m therefore glad to know a body of work has emerged to fill in the blanks about women’s experiences during those years.

Perhaps someone will someday write something of a fusion of the two, giving both their due.

Oh, but the real reason I wanted to comment was to note that my views on Kerouac shifted sideways recently when I came upon a video of him being interviewed on a TV show in Montreal—in French. To hear Kerouac speak in French, falteringly, but with a certain, inescapably “native” understanding of the language (it was his first language, after all), was a real eye-opener. I couldn’t read his work the same way again. (The show is called Le Sel de la semaine, and the interview is from 1967. If you haven’t seen it, it’s not hard to find on the “usual” video sites.) I’d be curious to know if this triggers any further ruminations.

Reblogged this on Literary Truce .

Thanks Desiree!

An excellent and well contrasted article, Sarah!