Selective Vision and Photojournalism

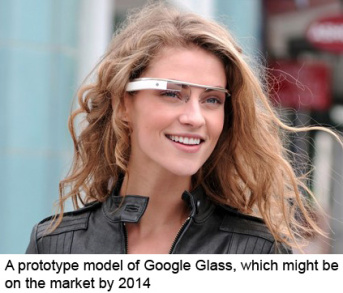

If you believe the hype, the next great technological frontier will be in the realm of vision, with

digital tools embedded in glasses

or in

contact lenses

to record, analyze and enhance what we’re seeing and doing. It’s called augmented reality. But some futurists have brought up another possibility, “deletive reality.” After all, if you can add things to your field of vision, why not take them away? “If pedestrians in New York or Mumbai don’t want to see homeless people, they could delete them from view in real-time,” Ayeesha and Parag Khanna

wrote on Slate.com

last year, describing the potential of pixelated contact lenses.

If you believe the hype, the next great technological frontier will be in the realm of vision, with

digital tools embedded in glasses

or in

contact lenses

to record, analyze and enhance what we’re seeing and doing. It’s called augmented reality. But some futurists have brought up another possibility, “deletive reality.” After all, if you can add things to your field of vision, why not take them away? “If pedestrians in New York or Mumbai don’t want to see homeless people, they could delete them from view in real-time,” Ayeesha and Parag Khanna

wrote on Slate.com

last year, describing the potential of pixelated contact lenses.

This idea, along with some recent stories about “smart” contact lenses, sparked comment in the

New York Times

and the

New Yorker

this week. Reading these columns, I was reminded of a shift that occurred at the beginning of the twentieth century. Both technological and moral, this shift also concerned selective vision. But ultimately, it had the opposite effect from the deletive future described above. Instead, it brought poor people sharply into focus.

This idea, along with some recent stories about “smart” contact lenses, sparked comment in the

New York Times

and the

New Yorker

this week. Reading these columns, I was reminded of a shift that occurred at the beginning of the twentieth century. Both technological and moral, this shift also concerned selective vision. But ultimately, it had the opposite effect from the deletive future described above. Instead, it brought poor people sharply into focus.

In most American cities before the 1880s, the rich and poor didn’t have much of a window into each others’ lives. They lived, worked, shopped and played in different neighborhoods, which were arranged to minimize contact between social classes. It was much the same in other countries–especially in the mother country, England. The friendship and concern showed by Downton Abbey ‘s aristocrats toward their servants is absurdly anachronistic. Real lords and ladies—even members of the rising middle class—aren’t likely to have known (much less cared) about the private lives of the poor.

Photography changed all that—not immediately, but gradually. As the medium overcame its technological limitations and became more flexible, various pioneers recognized that it could be used to increase empathy between social classes.

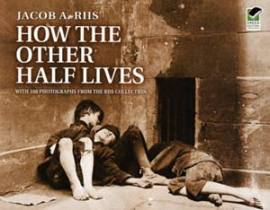

Jacob Riis wasn’t the first photojournalist (others included the Romanian

Carol Szathmari

and Englishman

Roger Fenton

). But he was among the first to focus on the poor, using flash photography to great effect in his groundbreaking book

How the Other Half Lives.

Jacob Riis wasn’t the first photojournalist (others included the Romanian

Carol Szathmari

and Englishman

Roger Fenton

). But he was among the first to focus on the poor, using flash photography to great effect in his groundbreaking book

How the Other Half Lives.

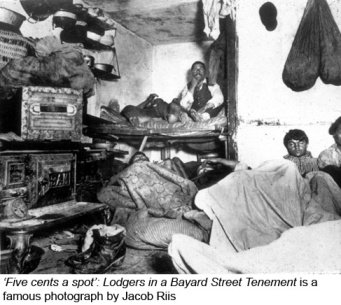

In 1887, the Danish-born Riis was working as a police reporter for the New York Tribune . Shocked by squalor and crime in the Five Points neighborhood, he was looking for a way to portray it viscerally. He tried sketching, but found he had no skill. Read about the new invention of flash photography, he immediately recognized its potential. With flash, he could patrol poor neighborhoods at night and take pictures of the inhabitants, unaware and unposed.

Riis’s methods were crude. He often accompanied police on raids, shooting images as soon as a door was opened. You can imagine the fright the poor immigrants in the flophouse pictured at right might have had when, woken from a well-earned sleep, they had a primitive, pistol-shaped flash gun pointed at them and fired. Ironically, though, this startled (or sleepy) look on his subjects’ faces gave Riis’s images a rawness and authenticity that made them influential. For the first time, New York’s “haves” got an intimate view into the lives of those less fortunate.

Riis’s methods were crude. He often accompanied police on raids, shooting images as soon as a door was opened. You can imagine the fright the poor immigrants in the flophouse pictured at right might have had when, woken from a well-earned sleep, they had a primitive, pistol-shaped flash gun pointed at them and fired. Ironically, though, this startled (or sleepy) look on his subjects’ faces gave Riis’s images a rawness and authenticity that made them influential. For the first time, New York’s “haves” got an intimate view into the lives of those less fortunate.

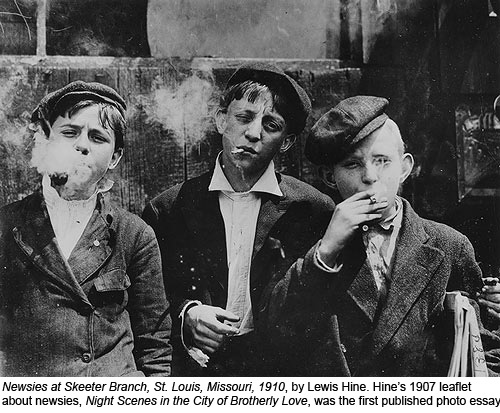

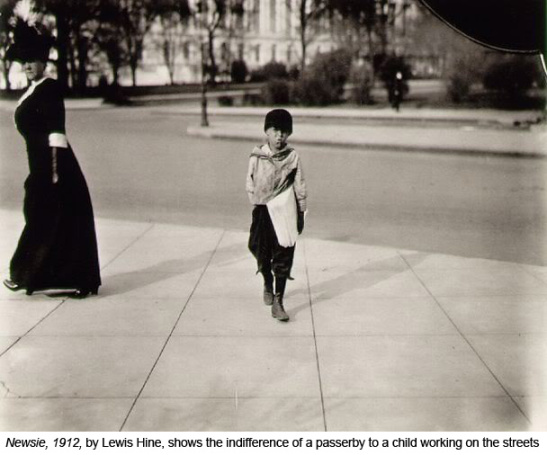

But Riis’s desire for social reform was motivated as much by disgust as by empathy. ( How the Other Half Lives describes the Chinese as “sinister,” blacks as “sensual,” and Jews as having “a native instinct for money-making.”) It took another photographer, Lewis Hine, to make the next leap—into a socially aware photojournalism that was also empathetic.

This was a leap indeed. As Daile Kaplan writes in Lewis Hine in Europe , “The appearance of indigent men and women in a ‘gentleman’s magazine’ might imply that some sort of relationship was called for between the reader (or viewer) and the person depicted: for a turn of the century nonprofessional, no such relationship existed. Until the emergence of the ‘social sciences’ the inclusion of such photographs in publications was seen as an invasion of privacy – not that of the people shown but of those who had to look at them.”

Hine’s rise as a photographer coincided with the emergence of Social Work as a field of study. His relationship with Paul Kellogg, a fellow student at Columbia University who became the editor of a progressive magazine called The Survey , was the key to his influence. Kellogg and Hine set out to create empathy for the poor, depicting them with delicacy and insight. Together, they took steps to reverse a prevailing mindset. Soon, looking at these kinds of images was no longer seen as an invasion of privacy. Instead, it was a moral imperative.

This was the foundation of the “concerned” photojournalism that flowered during the Great Depression and which has continued ever since. In the last couple of decades, though, there’s been something of a “deletive reality” in the media. The huge loss of editorial space for photo stories has made us less aware of the social issues around us. Photojournalists have had to become creative in finding outlets for their stories—using social media and art galleries, or partnering with nonprofits and corporations. There are also excellent sites promoting in-depth photojournalism, like SocialDocumentary.net . But the audiences for these places are often smaller.

Could the next step be a “deletive reality” where, in addition to not having the face inconvenient truths in the media, we no longer have to see them around us? It’s a stretch, but maybe not a ridiculous one. In the New Yorker blog post Upgrade or Die , George Packer describes a present where things are getting ever better for the top classes, and worse for the underclasses. Combine this widening economic gap with technological breakthroughs, and it’s not hard to imagine a time when those with the means to do so could remove unsightly or troubling items from their field of vision.

This would be reprehensible, of course, and an ironic coda to the work of visual pioneers like Riis and Hine. But perhaps the doomsayers are being too pessimistic. After all, what technology taketh away, technology can also give back. So who’s out there working on an empathy app?

This would be reprehensible, of course, and an ironic coda to the work of visual pioneers like Riis and Hine. But perhaps the doomsayers are being too pessimistic. After all, what technology taketh away, technology can also give back. So who’s out there working on an empathy app?

5 comments on “ Selective Vision and Photojournalism ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Excellent article Sarah – really enjoyed it. Never heard of this before I read your post and now I have to say I’m perturbed. The idea of “deletive reality” sounds really quite disturbing – there are already enough people out there who have a very skewed view of the world (usually politicians and bankers) so I really don’t think its a good idea to promote the deletion of ‘nasty’ or uncomfortable things from your line of sight. The consequences of this refusal to confront or acknowledge reality are truly frightening. Anyway, a fascinating read.

Thanks, PP. To be honest, I think many people are already fairly shielded and isolated from things that might be disturbing or upsetting, a trend that has been fast-tracked by the Internet and by people choosing to be exposed only to the groups and media outlets that confirm their own political and social beliefs. I see deletive reality (if it ever comes to fruition) as an extension of this–but it’s hard to really imagine it could work on a practical level.

If you want a laugh, this recent spoof of Google Glass by The Guardian shows the ridiculousness of deletive reality, pitching ultra-liberal ‘Guardian Goggles’: http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/2013/apr/01/guardian-goggles-augmented-reality-specs It’s very funny. Thank you Michael for sending me this link!

Reblogged this on maryfranceinmelbourne and commented:

Photojournalism is augmented reality

Thanks, Maryfranceinmelbourne. I appreciate the reblog!

Came late to article. I feel in some ways, interest-controlled mass media had already done this to us as societies for at least several decades, albeit using less “sophisticated” methods.

Still it does feel like the age of the “Peril Sensitive Sunglasses” from the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is upon us http://www.hhgproject.org/entries/perilsensitivesunglasses.html