A Novel of War Crimes and Punishments

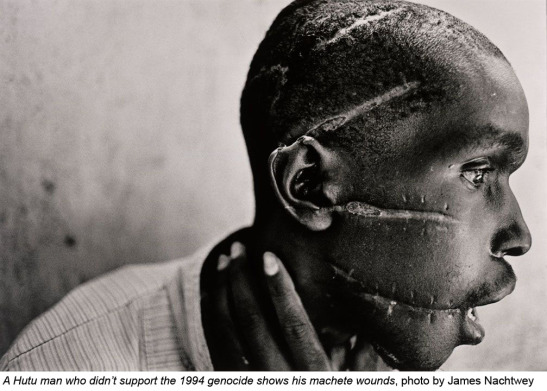

“If everyone could be there

just once, to see for themselves what white phosphorous does to the face

of a child, or what unspeakable pain is caused by the impact of a single

bullet or how a jagged piece of shrapnel can rip someone’s leg off – if

everyone could be there to see the fear and the grief,

just one time, then they’d understand that nothing is worth letting

things get to the point where that happens to even one person, let

alone thousands.” —James Nachtwey, photographer

No, we can’t all be there. Most of us hope we never will be. At the same time, having a visceral sense of wartime atrocities might be the only way we’ll be moved to find alternatives to the “unspeakable pain…the fear and the grief” Nachtwey talks about.

So we turn to photographs, film and literature.

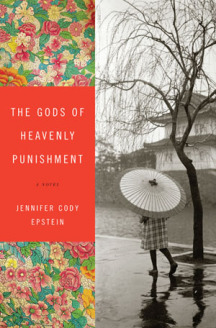

Jennifer Cody Epstein’s second novel,

The Gods of Heavenly Punishment

, is unusual in showing war from both sides of the battlefield. Covering approximately thirty years before and after the Second World War,

The Gods

follows five characters, both Japanese and American, as they deal with the build-up to war and the aftermath of Tokyo’s destruction.

Jennifer Cody Epstein’s second novel,

The Gods of Heavenly Punishment

, is unusual in showing war from both sides of the battlefield. Covering approximately thirty years before and after the Second World War,

The Gods

follows five characters, both Japanese and American, as they deal with the build-up to war and the aftermath of Tokyo’s destruction.

A downed American bomber pilot, a Czech-born architect who loves Japanese culture, a London-educated Japanese beauty, a troubled soldier-turned-photographer: all are brought together by circumstances leading up to one of modern history’s most devastating acts of war, the firebombing of Tokyo. In delicate prose, Cody Epstein brings war’s brutality onto a human scale, as her characters struggle to find meaning amid catastrophic loss.

“My approach was to try to understand the full horror of the war by immersing myself in it from both perspectives,” says Cody Epstein, whose first novel,

The Painter from Shanghai

, told the story of controversial Chinese painter Pan Yuliang. While some characters in

The Gods

, like American pilot Cam Richardson and builder Kenji Kobayashi, are steeped in their own cultures, others—Kenji’s cosmopolitan wife Hana and budding photographer Billy Reynolds—have a foot in both east and west. At the center of the story is Yoshi Kobayashi, Kenji and Hana’s precocious daughter, through whose eyes we witness the worst of the war.

“My approach was to try to understand the full horror of the war by immersing myself in it from both perspectives,” says Cody Epstein, whose first novel,

The Painter from Shanghai

, told the story of controversial Chinese painter Pan Yuliang. While some characters in

The Gods

, like American pilot Cam Richardson and builder Kenji Kobayashi, are steeped in their own cultures, others—Kenji’s cosmopolitan wife Hana and budding photographer Billy Reynolds—have a foot in both east and west. At the center of the story is Yoshi Kobayashi, Kenji and Hana’s precocious daughter, through whose eyes we witness the worst of the war.

Throughout, photography plays an important role in the narrative. Given a Brownie camera for his tenth birthday, Billy, who’s growing up in Japan, is told by his mother to “document your life as it is now… it’s a wonderful place you are living… we won’t be in Japan forever.” Subsequently, the older Billy’s photographs will educate complacent American viewers about the scale of Tokyo’s destruction. And casual photographs taken one balmy dusk will create an enduring bond between Yoshi and her glamorous, tragic mother.

Throughout, photography plays an important role in the narrative. Given a Brownie camera for his tenth birthday, Billy, who’s growing up in Japan, is told by his mother to “document your life as it is now… it’s a wonderful place you are living… we won’t be in Japan forever.” Subsequently, the older Billy’s photographs will educate complacent American viewers about the scale of Tokyo’s destruction. And casual photographs taken one balmy dusk will create an enduring bond between Yoshi and her glamorous, tragic mother.

Cody Epstein, who (full disclosure) is a friend and mentor, spoke to The Literate Lens recently about the way she integrated photography into this story of ordinary people caught up in violence and devastating loss.

Literate Lens: You start each section of the novel with a photograph (or in two cases, an illustration). At what point did you start looking for photographs, and how did you find them?

Jennifer Cody Epstein: I really was looking for them from the very beginning. I find visual “prompts” really helpful when I’m trying to write; for my first novel ( The Painter from Shanghai) I would surround myself with printouts of Pan Yuliang’s paintings and stare up at them when I got stuck. As I worked on Gods I kept a file of interesting images I came across. Most of them I found online, in the course of researching various elements of my story. Most I just sort of stumbled upon. Some, though—like the image of the Doolittle Raiders taking off from the U.S.S. Hornet—I specifically set out to find, to help me get a sense of what I was trying to write. It didn’t occur to me until well into the process that I wanted to actually put them in the book.

LL: Did any of the ones you found inspire characters in the novel?

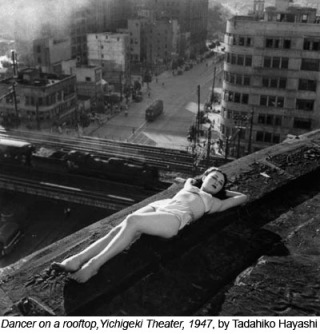

JCE: I already had an image of Hana Kobayashi, the attractive British-educated woman who has trouble readjusting to Japanese life, in my head from some of the research I’d done. But when I came across the image “Dancer on a Rooftop” it really stopped me in my tracks. I just thought to myself:

That’s her. There she is.

I became a little obsessed by the image, actually—it just seemed to sum up so much of what I was trying to write about: West and East, modernity and tradition, serenity and wartime, hope and devastation.

JCE: I already had an image of Hana Kobayashi, the attractive British-educated woman who has trouble readjusting to Japanese life, in my head from some of the research I’d done. But when I came across the image “Dancer on a Rooftop” it really stopped me in my tracks. I just thought to myself:

That’s her. There she is.

I became a little obsessed by the image, actually—it just seemed to sum up so much of what I was trying to write about: West and East, modernity and tradition, serenity and wartime, hope and devastation.

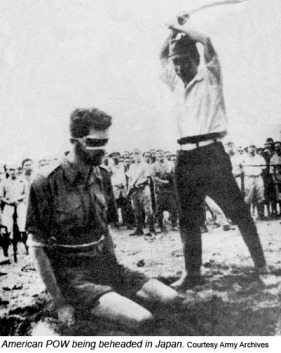

Another image that helped shape one of the story threads was a chilling photo of an American POW about to be beheaded by a Japanese officer. I’d certainly read about the Japanese Army’s obsession with this sort of execution, but this particular image really drove it home for me. All I could think about was “What’s going through that prisoner’s mind?” Which, in turn, led me pretty directly to the storyline of Cam Richards, my fictional Doolittle Raider.

LL: Did many Western photographers (professional or amateur) take photographs in pre- and post-war Japan?

LL: Did many Western photographers (professional or amateur) take photographs in pre- and post-war Japan?

JCE: I don’t know about numbers, but I do know of one in particular whom I partly used as inspiration for the character of Billy Reynolds. His name was Joe O’Donnell, and he was a U.S. Marine who took extensive photographs of Japan right after the surrender—including some iconic images of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

LL: What research did you do in order to write the character of Billy?

JCE: Ha! Well, I guess I just partly answered that. But I also did research into the sorts of cameras he would have had at various points in his life—what kind of camera his mother might have given him as a boy growing up in Japan (I opted for a Brownie) and what he may have used in the 1940s in Japan (I went with a Contax). I did a little research into photographic styles of that era, but for the most part I scoured the Internet for old photographs of postwar Tokyo and tried to imagine what he might have seen, what might have caught his interest.

LL: Can you tell us something about Hayashi Tadahiko, the Japanese photographer who took several of the photographs you feature in the book?

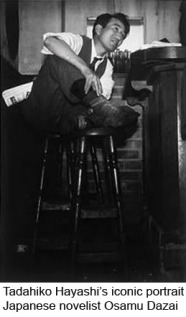

JCE: I discovered him through that photograph I mentioned before—“Dancer on a Rooftop”—but realized upon researching a little that he’d taken a few other photos I’d admired in the past, including an iconic one of the Japanese novelist Osamu Dazai about to topple off a bar stool in the Ginza. He was born in 1918 into a family of photographers—interestingly, his mother was the real talent in the family—so he learned the basics of the trade growing up, and was skilled as a portrait artist. He went to photography school in Tokyo, where he was apparently such a big partier (maybe how he got that great shot of Dazai?) that his family finally cut him off financially. He spent the latter part of the Pacific War in Beijing and then returned to Tokyo, where he took pictures of orphans (like “Shoeshine Boy,” which I also use in the novel) and the high life alike.

JCE: I discovered him through that photograph I mentioned before—“Dancer on a Rooftop”—but realized upon researching a little that he’d taken a few other photos I’d admired in the past, including an iconic one of the Japanese novelist Osamu Dazai about to topple off a bar stool in the Ginza. He was born in 1918 into a family of photographers—interestingly, his mother was the real talent in the family—so he learned the basics of the trade growing up, and was skilled as a portrait artist. He went to photography school in Tokyo, where he was apparently such a big partier (maybe how he got that great shot of Dazai?) that his family finally cut him off financially. He spent the latter part of the Pacific War in Beijing and then returned to Tokyo, where he took pictures of orphans (like “Shoeshine Boy,” which I also use in the novel) and the high life alike.

One thing that was particularly interesting about his style to me was that he wasn’t afraid to stage things: he clearly wanted his images to tell stories, and he would use props and other devices to tell them.

One thing that was particularly interesting about his style to me was that he wasn’t afraid to stage things: he clearly wanted his images to tell stories, and he would use props and other devices to tell them.

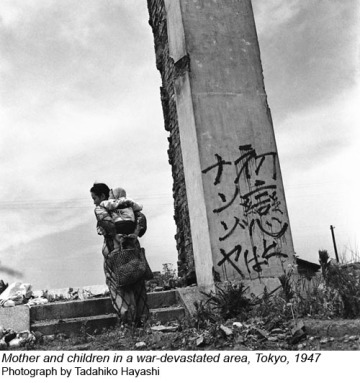

In another picture of his—of the woman walking in rubble, next to a pillar with “What was the point” scrawled on it (at left)—it is said that he actually painted the graffiti himself. His interest in narrative is also evidenced by the subject of his first book of photographs, titled Shosetsu no Furusato, for which he travelled around Japan photographing settings that have been described in various Japanese novels.

LL: Were there important photographs you found in the course of your research that didn’t make it into the book?

JCE: The one of the POW about to be executed didn’t make it—it was really just too grim, I thought. There was also a great photograph of a Japanese woman in a white dress sitting on a Western-style couch that also reminded me of Hana Kobayashi, but in the end I didn’t have room for it (though I use it on my site).

JCE: The one of the POW about to be executed didn’t make it—it was really just too grim, I thought. There was also a great photograph of a Japanese woman in a white dress sitting on a Western-style couch that also reminded me of Hana Kobayashi, but in the end I didn’t have room for it (though I use it on my site).

LL: In the final section of the novel, Billy’s photographs of postwar Tokyo are exhibited in California and a disbelieving viewer remarks, “maybe [the photographer] made it look worse than it was.” The comment really stings for the reader after witnessing the devastating violence of the Tokyo firebombing earlier in the novel–and it offends Yoshi, the survivor who overhears it. What were you trying to get at with that comment?

JCE: I think I was trying to highlight the fact that people—myself included, until I began writing this book–simply don’t consider the firebombing in the same way they do the atomic bombings. And while it’s certainly true that the atomic bombs were astoundingly devastating, and worked in a way that continues to fascinate and horrify us even today, the firebombs that LeMay used were also incredibly devastating and a far cry from “traditional” bombs used up until that moment. The attack on Tokyo actually killed more people initially than did the attack on Hiroshima, and had three times the fatality rate of Dresden. So I guess the main point is that bombing is a catastrophic event, no matter what the science is behind the bombs that are used.

LL: Billy’s photography is a thread that ties together a couple of sections of the novel, and it enables you to end on a very poignant note. At what point in the writing did you decide to end with a photograph, and why?

JCE: It actually came rather late in the game for me, and coincided with my decision to have Billy take snapshots of Yoshi and Hana in 1930s Karuizawa. That scene is one of the first in the book, but I wrote it well after I wrote most of the others. Which was typical of the way this novel evolved—it was anything but chronological! I’d originally imagined a very romance-novel sort of ending, where Cam the pilot ends up meeting Yoshi and the two fall in love. But…

blech.

Gag.

Right? Every time I tried to write that it just seemed totally contrived, out of step with what the novel ended up being. But as I wrote the new openings, I realized those photographs that Billy takes so obsessively could be the things that bring the novel full-circle—and effectively reunite Yoshi with her mother. Which was really where the book really wanted to go emotionally.

JCE: It actually came rather late in the game for me, and coincided with my decision to have Billy take snapshots of Yoshi and Hana in 1930s Karuizawa. That scene is one of the first in the book, but I wrote it well after I wrote most of the others. Which was typical of the way this novel evolved—it was anything but chronological! I’d originally imagined a very romance-novel sort of ending, where Cam the pilot ends up meeting Yoshi and the two fall in love. But…

blech.

Gag.

Right? Every time I tried to write that it just seemed totally contrived, out of step with what the novel ended up being. But as I wrote the new openings, I realized those photographs that Billy takes so obsessively could be the things that bring the novel full-circle—and effectively reunite Yoshi with her mother. Which was really where the book really wanted to go emotionally.

——————————————————–

Buy The Gods of Heavenly Punishment.

Visit Jennifer Cody Epstein’s web page.

7 comments on “ A Novel of War Crimes and Punishments ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

This came out so beautifully–and I love the additional images! Thanks, Sarah. One of my favorite discussions thus far 🙂

This was a really interesting article, especially as both Jennifer and I have novels coming out at the same time that deal to a certain extent with the same topic – the Tokyo fire bombings. This was also the subject of the Oscar-winning documentary Fog of War, the reflections of former US Secretary of State, Robert MacNamara. I agree with Jennifer that the firebombings tend to get lost amidst the horrors of the atomic bombings but they were just as horrific none the less. In fact, if you were to look at photographs of Tokyo after the March 1945 operations, you would think you were looking at a picture of Hiroshima or Nagasaki. I would love to read Jennifer’s book eventually – I cannot at the moment as I try to avoid novels on the same subject matter immediately before and after publication. But if you get a chance to read An Exquisite Sense of What is Beautiful, Sara, I would be interesting to hear your reflections on both novels.

Thanks, David! Been meaning to email you actually. I asked my mother-in-law if she could bring your novel over to me when she visits here in May. She asked my permission to read it beforehand, and said she thoroughly enjoyed it and thought it was very well done. She’s no pushover, either! I’m very much looking forward to reading it next month, and will share my thoughts with you.

Yes, your mother-in-law actually wrote to me via Sofia with her kind comments. By the way, do you know if Jennifer is coming to the UK to promote her book over here?

I don’t think so, David, but I’ll let you know if that changes!

I was curious about the beheading photo – how did the Army Archives come to have such a perfect incrimination of the Japanese military?

The Internet seems to provide a credible backstory to that picture: It’s actually an Australian soldier, Leonard Siffleet, who was captured on a reconnaissance mission in 1943. It doesn’t really affect the message of the picture — it’s a summary execution of a PoW — although perhaps this particular form of execution was not routine.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leonard_Siffleet

DAn.

I’m looking forward to readint this novel.