Into the Light: Robert Burley’s Book on the End of Analog

Ah, the old darkroom days. Giving up daylight hours to hide away in the dark, like a mole in a burrow. Shuffling from enlarger to sink, breathing in a noxious variety of chemicals. Knowing it was worth it for that moment when an image would start to appear, materializing like a mirage or magic trick in the developing tray.

Ah, the old darkroom days. Giving up daylight hours to hide away in the dark, like a mole in a burrow. Shuffling from enlarger to sink, breathing in a noxious variety of chemicals. Knowing it was worth it for that moment when an image would start to appear, materializing like a mirage or magic trick in the developing tray.

You may or may not think that analog film, and the art of darkroom printing, are dying. Certainly, film has its vociferous defenders: many of them have shown up to comment on Magnum and the Dying Art of Darkroom Printing , the most widely-read post on this site. Nevertheless, nobody can deny that digital technology has delivered blow after blow to the industry that produces analog film. Considering the force of the blows, it’s remarkable film is still on its feet at all. It may not be for much longer.

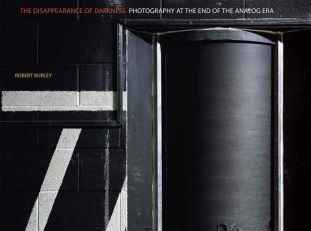

In The Disappearance of Darkness: Photography at the End of the Analog Era , Robert Burley delivers a thoughtful visual essay about the end of the industrial film era. Burley, a photographer and professor at Ryerson University in Toronto, was prescient enough to see in 2005 that the industry was changing at light speed. With an assertively old-fashioned, analog view camera in hand, he began documenting a world in decline.

Burley’s approach is deep rather than wide. As he writes in his introduction, the size and reach of major players like Kodak and Polaroid “would have made any kind of comprehensive history of the industry unworkable.” Instead of aiming for broad coverage, he went to places he knew well, having visited them in the past or used their products for years.

Using his connections, he managed to gain access to areas and places generally off-limits (the film companies’ secrecy and paranoia about their products persists even as their markets are evaporating). Seeing these huge, abandoned industrial facilities, one comes to understand that a company like Kodak was, in many ways, sabotaged by its own success. In other words, the production facilities necessary for color film are so large and expensive that Kodak could only make profits if film was in every home. Once the market began to falter, the products were immediately threatened.

All the photographs in The Disappearance of Darkness are artful and beautifully rendered. Inevitably, some are more interesting than others. Photographs of the outside of drab industrial buildings, however well-composed and thoughtful, tend to merge together after a while. But then there are inspired shots, like the one of Betsy, a mannequin formerly used by Polaroid to test skin tones, staring out at a weed-filled courtyard from an abandoned Polaroid facility in the Netherlands. Or the sequence that involves the failed implosion of a Kodak-Pathé building in Chalon-sur-Saone, France–the building’s stubborn refusal to fold being a metaphor for a business clinging to life.

The most detailed portion of the book concerns Kodak Canada, a facility in Burley’s own back yard in Toronto. The plant closed in 2005, and Burley managed to get in immediately afterward. Cameras were never allowed behind what the workers referred to as “the silver curtain,” and it’s fascinating to get a glimpse into the former film hopper, where layer upon layer of light-sensitive chemicals used to be laid onto polyester film at punishingly high tolerances. As Burley writes, “After peering behind ‘the silver curtain,’ the phrase ‘economy of scale’ comes into sharp focus; it’s difficult to imagine how this process could ever be done successfully on a small scale.”

It isn’t all bad news. Burley also visits the Ilford Company in England, where black-and-white film and papers are still being produced on a small scale. Black-and-white film and papers are easier to produce than their color counterparts, and despite being forced into bankruptcy in 2004, Ilford has managed to survive. “If film is to survive into the digital era, it is likely that it will do so in its simplest and original form, black-and-white, and be manufactured solely as an artist’s material,” Burley writes.

It isn’t all bad news. Burley also visits the Ilford Company in England, where black-and-white film and papers are still being produced on a small scale. Black-and-white film and papers are easier to produce than their color counterparts, and despite being forced into bankruptcy in 2004, Ilford has managed to survive. “If film is to survive into the digital era, it is likely that it will do so in its simplest and original form, black-and-white, and be manufactured solely as an artist’s material,” Burley writes.

In these days of tweets and soundbites, The Disappearance of Darkness is itself a bit of anachronism. An elegiac coffee-table book, its images and essays should be consumed slowly. In addition to Burley’s thoughtful introduction, American curator Alison Nordstrom contributes an essay that analyzes Burley’s work in the context of its historical moment, and French curator François Cheval remembers the history of the Kodak plant in Chalon-sur-Saone–the town where, in 1825, inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce produced the world’s first photograph.

How should we mourn the passing of film? Photography’s digital transformation has been so fast and overwhelming that having a book like this feels necessary, like going to a wake where the dead person’s life is celebrated through speech, image and song. But mournful as it may seem, Burley doesn’t intend for his book to be a Luddite’s lament for a simpler, better time. Rather, it’s a chance to pause and reflect on a changing medium. “Technologies are made to be transformed, and redefined, even reinvented,” he concludes. “If this book is a eulogy for film and the miraculous process it made possible, both now consigned to the past, it is also an article of faith that anything is possible.”

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Web site for The Disappearance of Darkness , with a trailer for the book.

5 comments on “ Into the Light: Robert Burley’s Book on the End of Analog ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Great article, Sarah!

What I want to know is that if film is dying, why are so many photographers wanting to return to it? Already there is a movement to return to film on the west coast. Could it be that some of digital’s luster has worn off?

Go dig out that camera… http://www.butkus.us

I just bought a Polaroid Land 350 and a dozen or so boxes of (brand new) Fuji 100 and 3000 film and I am having a total blast! Always a curiosity to onlookers and at parties, ridiculously affordable and amazingly cool shots and it scans really well if you want to tweak and post. Maybe I’m going backwards but at the moment it’s a lot more fun than forward. I’ve got an SX70 on the way and several boxes of film from the “Impossible Project”.

Thanks, Steve. Yes, the Impossible Project is doing great work to keep the spirit of Polaroid alive. Best of luck with your shooting, and please post a link to an image if you have one.