End of the Road: An Interview with Jeff Jacobson

Provia, Agfapan, Kodachrome, Plus X, Polaroid Type 55. In the last few years, the list of films being discontinued has gotten longer, prompting cries and groans from desolate photographers. Imagine, then, hearing that the film you’ve been using for almost three decades is disappearing

and

finding out at the same time that you have cancer. The end of your film, the beginning of life’s end. The two slamming together like the punchline of a very bad joke.

Provia, Agfapan, Kodachrome, Plus X, Polaroid Type 55. In the last few years, the list of films being discontinued has gotten longer, prompting cries and groans from desolate photographers. Imagine, then, hearing that the film you’ve been using for almost three decades is disappearing

and

finding out at the same time that you have cancer. The end of your film, the beginning of life’s end. The two slamming together like the punchline of a very bad joke.

That’s what happened to Jeff Jacobson. A former Magnum photographer known for his quirky style, Jacobson was one of the first art photographers to use color film exclusively. For his 1991 book My Fellow Americans he traveled the country, capturing the look and mood of a decade. His offbeat, stridently colorful images of faith healers and glitzy dancers conveyed the brittle, tarnished glamor of the Reagan years, nodding directly at Robert Frank’s seminal 1950s book The Americans .

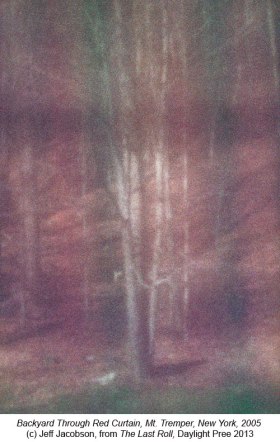

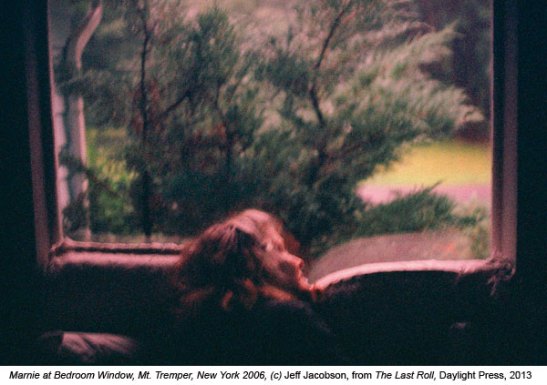

Over time, Jacobson refined his style by using Kodachrome 200. He pushed it two stops in the developing process, which yielded a grain more typical of black-and-white film. This became his look, his signature. After his chemotherapy treatments, confined indoors at his home in Mount Tremper, New York, he started making a visual diary. At first, he was just thinking in terms of individual images. Then Kodak announced it was ceasing production of Kodachrome, and the project acquired new layers. No longer just about moments of grace amid personal loss, it was now also about enshrining a part of photographic history. His new book,

The Last Roll

, was born.

Over time, Jacobson refined his style by using Kodachrome 200. He pushed it two stops in the developing process, which yielded a grain more typical of black-and-white film. This became his look, his signature. After his chemotherapy treatments, confined indoors at his home in Mount Tremper, New York, he started making a visual diary. At first, he was just thinking in terms of individual images. Then Kodak announced it was ceasing production of Kodachrome, and the project acquired new layers. No longer just about moments of grace amid personal loss, it was now also about enshrining a part of photographic history. His new book,

The Last Roll

, was born.

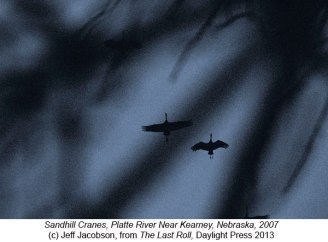

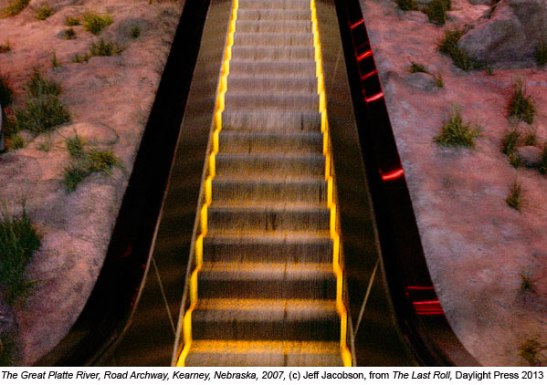

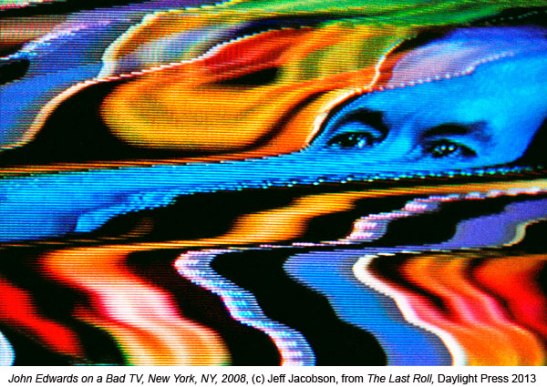

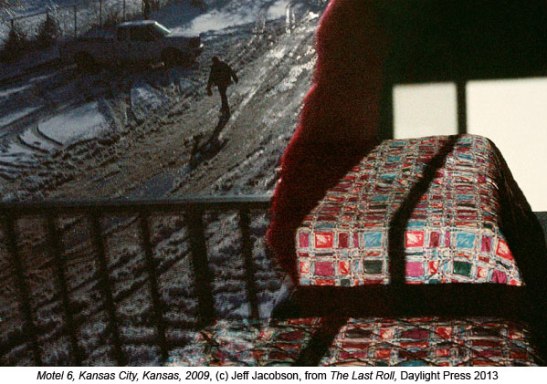

A tone poem, mysterious and radiant, The Last Roll celebrates life in all its messy glory. There are luminous, almost mystical shots of nature; raucous snatches of urban graffitti, and one or two shots that verge on the satirical–like the jangling, distorted image of John Edwards’ face on a flickering television screen, in which Edwards’ nose elongates to Pinocchio proportions. An escalator ascends incongruously through a desert landscape, as if to another world; a gorgeous, concentrated teal-blue sky is photographed through a car’s windscreen that seems to have a dead insect smeared across its surface. Jacobson acknowledges that the images in The Last Roll , and the way they’re sequenced, are full of ambiguity–but that’s the way he likes it. It’s the sensibility of a man battling loss, looking for meaning, finding transcendence in the everyday.

“This is the most emotional work I’ve ever done,” Jacobson says. “These are very direct translations of my inner psychic state.”

Images from The Last Roll are currently on view at the Center for Photography in Woodstock. Jacobson spoke to The Literate Lens from his home in Mount Tremper.

Literate Lens: First of all, how is your treatment going?

Jeff Jacobson: I’m doing an experimental drug trial, which has been fairly uneventful, but I had to do a round of chemotherapy first, and that was pretty awful. At some point they’ll be removing my T-cells, genetically modifying them to destroy cancer cells, and putting them back. I’ll run a high fever at some point and will have to go into hospital. So it won’t be much fun.

LL:

The Last Roll

is about mortality and ephemerality. You were close to your grandmother before she died. In the book you write about taking a picture of her in 1973, and how it started your love of photography. What was special about that picture?

LL:

The Last Roll

is about mortality and ephemerality. You were close to your grandmother before she died. In the book you write about taking a picture of her in 1973, and how it started your love of photography. What was special about that picture?

JJ: It was the look of unconditional love on her face, no question. As a child I wasn’t close to her, but we became close at the end of her life. The picture is just a straight-ahead, black-and-white portrait outside her house, but she’s standing next to the house foundation, which is pebbled, and it somehow mirrors the texture of her skin. When I gave a print of it to my parents, my father got upset and told me I’d made her look old. I said, she is old! It was an early lesson in the power of photographs to get under people’s skin.

LL: You didn’t become a photographer immediately. How did you become a civil rights lawyer, and why did you make the transition to photography?

JJ: I grew up in Des Moines in the 1950s, a Jewish kid in a Christian American environment. I always had a sense of politics. Originally, my impetus to go to law school was to dodge the draft, which didn’t work because around that time they abolished exemptions for law school! But I was in school in D.C. in the late 1960s, when all hell was breaking loose on the national stage. I started getting fascinated in the law. Later, I worked for the ACLU in Atlanta and fought a case that ended up being a prelude to Roe vs. Wade. Meantime I was doing photography as a hobby, and in 1974 I did a summer workshop with Charles Harbutt, which was the breakthrough. At the time, Charlie was president of Magnum Photos, and doing the course with him made me realize I could live that life if I wanted it. I went back to Atlanta and promptly resigned from the ACLU.

LL: How did you get into shooting color film? Not too many ‘serious’ photographers in the 1970s were doing that.

JJ: When I worked in black and white, I wasn’t doing anything groundbreaking. Until I started working in color I don’t think I was doing anything terribly unique at all. The move to color happened by accident. George Wallace, who was running for president at the time, held a rally in Boston when I was working there. I went and shot it in color, playing around and doing long exposures. When I saw the film I never looked back. I knew right away that I saw in color, not black and white.

LL: What made you so sure?

JJ: For whatever reason, I could be a lot more playful in color. The images had an immediacy that my black-and-white images never had. I could never understand how you translated a world that was in color into the tones of black and white; that never made any sense to me. With color I could respond to whatever was in front of me and it was direct, not abstracted into grey tones.

LL: You went on the road, photographing the 1976 presidential campaign. What was that like?

JJ: After shooting the Wallace rally in Boston I quit my job, traded my old car for a van and started following the presidential primaries around the country. It was much easier to do that back then. It was great, a fantasy come true. I was at a very political stage in my life and it was a way to express all my feelings, learn the ropes without working for anyone. I covered both parties, it was a wide open year. Ford was an incumbent president but he wasn’t a strong candidate; Reagan was running against him and there were a whole lot of Democrats. The extreme right wing candidates were more interesting to me because the scene around them was strange. I have an image of Wallace speaking: he’d already survived an assassination attempt and he had security all around him. It’s just a picture of him on the stage with his security guys, but in my mind it looked a bit like Goebbels with Nazi brownshirts around him.

LL: Kodachrome 200 became your color film of choice. What did you like about it?

JJ: Kodachrome was a very unique film because it was so rich. It was basically a black-and-white film on which there were layers of dye, and that made it totally different from any other film. It gave me a color palette and a texture I just couldn’t get anywhere else. When I started pushing Kodachrome 200 two stops in the developing bath, I got a graininess I’d never seen before with color. I always loved grain in black-and-white film, so that’s what I did for the rest of the time I had Kodachrome.

LL: What was your reaction when Kodak announced it was discontinuing Kodachrome?

JJ: I remember the day they announced it. It was 2007, and I was on a trip for my wedding anniversary with my wife. It was supposed to be a nice time, but I was all upset and pissed off. Kodak had already screwed up the market for Kodachrome by making a new processing machine that didn’t work, so I knew it was coming, but even so, it was a blow.

LL: For The Last Roll , you were initially shooting inside your house while you recovered. Did being confined indoors change the way you started seeing?

JJ: I think it did, but I didn’t know it at the time. Like everything I’ve done, I didn’t set out to do this project, it just happened. I was taking pictures in my house because I couldn’t go outside, and it was only much later that I saw how this body of work was emerging. There are so many pictures in the book from that early period that, for me, are very direct translations of my inner emotional state. I really like them for that reason. At the time, though, I was just responding to what I was seeing, which I always think makes the most interesting photograph. For me, photography is an immediate medium. When you’re thinking too much, it becomes conceptual, which can deaden it. You’re killing the goose that lays the golden egg.

JJ: I think it did, but I didn’t know it at the time. Like everything I’ve done, I didn’t set out to do this project, it just happened. I was taking pictures in my house because I couldn’t go outside, and it was only much later that I saw how this body of work was emerging. There are so many pictures in the book from that early period that, for me, are very direct translations of my inner emotional state. I really like them for that reason. At the time, though, I was just responding to what I was seeing, which I always think makes the most interesting photograph. For me, photography is an immediate medium. When you’re thinking too much, it becomes conceptual, which can deaden it. You’re killing the goose that lays the golden egg.

LL: Did knowing that you were shooting a nearly obsolete film make those last Kodachrome images seem more precious, more weighted?

JJ: I just didn’t go there. I bought up a lot of Kodachrome, and people gave it to me as well. Right at the end of the project, Alex Webb gave me fifty rolls of film. That kind of support was very satisfying, and I had plenty of film, it was all I could do to shoot it. I planned a couple of trips just to use it all up. By the end of the project, I’d really dealt with that whole issue of the preciousness of it.

LL: How do you work these days? Do you shoot digitally?

JJ: Ever since Kodachrome ended, I’ve been working with nothing but a digital camera. It’s totally different. Well, not totally different: it’s still photographing. I’ve been using a Lumix with a Leica lens: it’s a fantastic camera that looks like any tourist camera you’ve ever seen. I’m doing stuff I thought I’d never do, and I look like a tourist, so I can get away with things I couldn’t do before. What I don’t like about digital is its clarity and crispness, which can look unreal. But this camera doesn’t have a huge sensor, it’s funky, and I’m messing with it a bit, adding grain to the pixels. I have it with me all the time, and I use it like a diary.

LL: The last roll of Kodachrome was developed in 2010. What was it like to end the project?

JJ: By the end it felt fine. As a matter of fact, the reason I link Kodachrome with my cancer is that it was the same lesson. Cancer presented me with my own physical mortality, it said to me, hey, you’re not going to live forever. Kodachrome presented me with creative mortality. Kodachrome was the creative tool I’d used to create most of my work. Then gone, with the snap of a finger it’s gone. It reinforced the lesson that nothing is permanent. The only law of the universe is that everything changes. It was an exercise in letting go.

———————————————————–

The Last Roll is showing at the Center for Photography in Woodstock through June 13, 2013. For opening hours and directions, click here .

Visit Jeff Jacobson’s web site .

Buy The Last Roll and other Daylight books here .

2 comments on “ End of the Road: An Interview with Jeff Jacobson ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

I love this piece Sarah. Beautifully written and utterly moving.

Wonderful article. His work certainly is interesting, and the text, as well as his life, a testament to enjoy our passions to the fullest.

Neil Gaiman said it best: “Make good art!”