Damaged Goods: An Interview with Larry C. Price

Where did the gold for your wedding ring come from, and what was involved in its production? How about those fancy running shoes, or the surprisingly cheap silk shirt you bought your sister for her birthday? What about the 70% cacao chocolate you like to nibble after dinner?

Where did the gold for your wedding ring come from, and what was involved in its production? How about those fancy running shoes, or the surprisingly cheap silk shirt you bought your sister for her birthday? What about the 70% cacao chocolate you like to nibble after dinner?

These kinds of questions have been nagging at photojournalist Larry C. Price for many years. But it wasn’t until last year that he had a chance to pursue them. In August 2012, Price, who’d been working as the photo editor of the Dayton Daily News, resigned in protest from his job when he was asked to lay off half his staff. With time on his hands, the way forward was clear: he would go back to his roots.

Since graduating from college, Price has been doing hard-hitting photojournalism, either as a staff photographer for newspapers or on his own time. His back catalog isn’t too shabby: he won the 1981

Pulitzer Prize

for spot news photography, for coverage of the 1980 coup in Liberia, and a second Pulitzer for feature photography in 1985, for a portfolio documenting civil wars in Angola and El Salvador. He’s a former

National Geographic

photographer and one of an elite group of Olympus Visionaries (which is how I met him).

Since graduating from college, Price has been doing hard-hitting photojournalism, either as a staff photographer for newspapers or on his own time. His back catalog isn’t too shabby: he won the 1981

Pulitzer Prize

for spot news photography, for coverage of the 1980 coup in Liberia, and a second Pulitzer for feature photography in 1985, for a portfolio documenting civil wars in Angola and El Salvador. He’s a former

National Geographic

photographer and one of an elite group of Olympus Visionaries (which is how I met him).

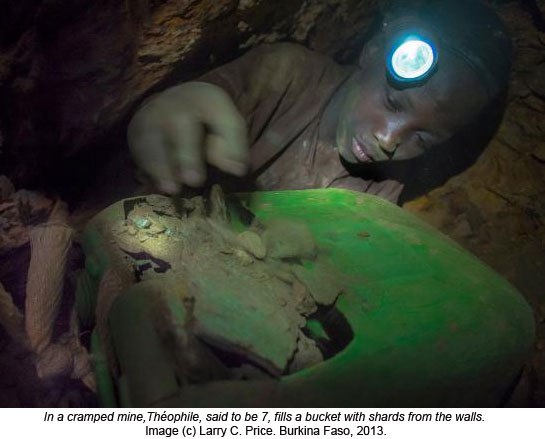

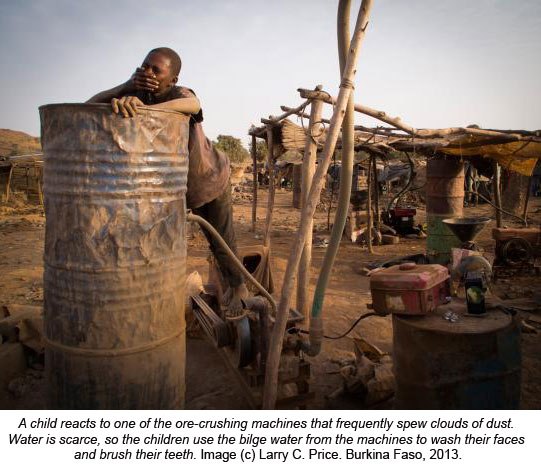

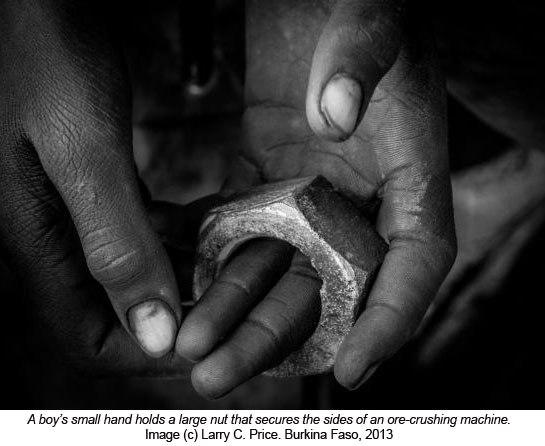

But now, what he really wanted to focus on was child labor. Ever since the 1980s, when he’d photographed child soldiers working in Nicaraguan sugar cane fields, Price had wanted to photograph child workers more extensively. In an age of globalization and cheap consumer goods, illuminating this issue seemed more important than ever. Many of the cheap goods we enjoy are made, quite literally, on the backs of child workers–and Price thought it was time to show people that.

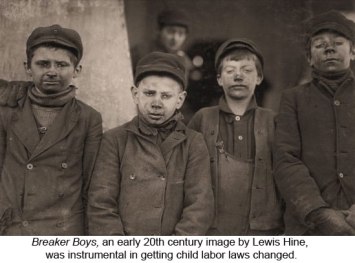

His work harks back to a time a hundred years ago, when Lewis Hine exposed the blight of child labor in the United States. Working for the National Child Labor Commission, Hine spent over a decade going undercover to coal mines, cotton mills, canneries and glass factories. His heartbreaking images of child workers were instrumental in getting new child labor laws passed, and Price—who plans to make this a long-term project—is working in the same vein. Like Hine, he says, “I have a point of view, and I’m not making any excuses for that.”

His work harks back to a time a hundred years ago, when Lewis Hine exposed the blight of child labor in the United States. Working for the National Child Labor Commission, Hine spent over a decade going undercover to coal mines, cotton mills, canneries and glass factories. His heartbreaking images of child workers were instrumental in getting new child labor laws passed, and Price—who plans to make this a long-term project—is working in the same vein. Like Hine, he says, “I have a point of view, and I’m not making any excuses for that.”

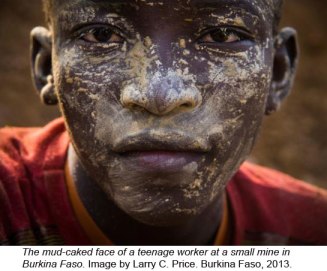

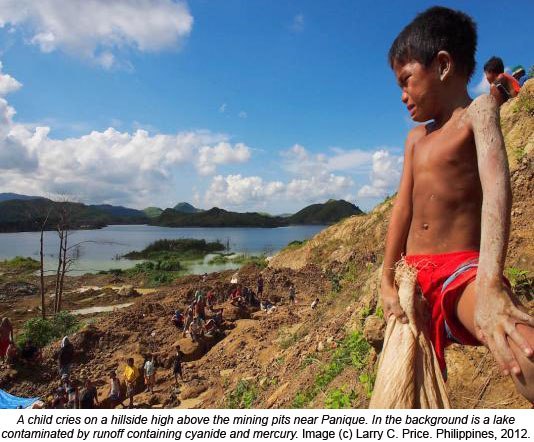

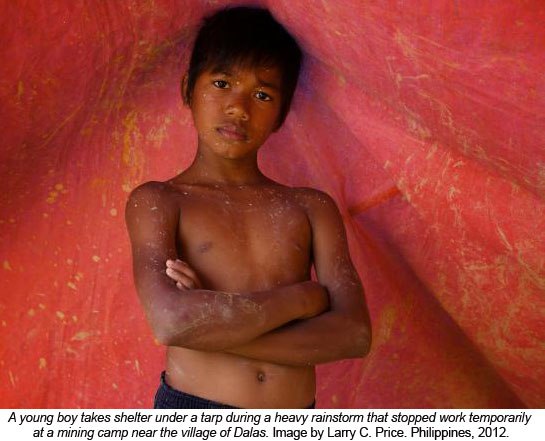

So far, Price has photographed child laborers at gold mines in the Phillippines and Burkina Faso; he plans to broaden the project to other industries and other countries soon. Last week, he spoke to The Literate Lens from his home near Dayton, Ohio.

Literate Lens: First of all, what’s it like to be out in the field again?

Larry Price: I love it! I’ve slipped back into it pretty easily. In my life, I’ve gone back and forth between editing and shooting more times than I can count. Shooting is my preference, it’s wonderful to be able to do creative work. I feel there’s a mission here that I’m really at peace with, and there seems to be some interest in it.

LL: Why child labor?

LP: I feel that the public’s general awareness of this problem hasn’t kept up with the way it’s swelled through globalization. Some of the numbers are staggering: in western Africa there are 200,000 child workers in the mining sector alone. I felt that now was a really critical time to talk about these issues, so that people can understand and try to make informed decisions about where they get their goods and services.

LL: How did you get started, research-wise?

LP: At first, I was just doing research on the Internet. Typically, I start with a broad idea. You develop notions and see where they lead—it unfolds over period of months. Going to gold mines was actually a spinoff of another idea I had, to do a project on environmental lead poisoning in children. I started researching that, and I got friendly with some NGOs doing work in that field. They suggested things for me to read. I read academic reports from various sectors, and there were long bibliographies at the end, so I could find people who’d done fieldwork in these areas. I’ve talked to people from Scotland, Scandinavia, Africa, all over. Research has become easier now because I’ve met these people.

LL: Very few photographers are doing work on child labor these days, compared, say, to war reporting. Why do you think that is?

LL: Very few photographers are doing work on child labor these days, compared, say, to war reporting. Why do you think that is?

LP: I think the reason is that it’s just really hard. Access is frustrating, you have to be careful and street smart, and you’re dealing with people who probably don’t want you doing what you’re doing. Working in the Phillippines was difficult for me at times. For each of the six locations I went to, I had to have meetings with local officials just to get to the areas. Once I was there, there was a lot of suspicion. I just had to operate as best I could.

LL: Did you ever have any tense situations?

LP: A couple, yes. One day in the Phillippines, I was photographing some independent miners who’d been digging pits, with permission, near a large mining operation. The second day I was there, the large corporation brought in a bunch of guards, made everyone leave, and bulldozed the mines the men had been digging for months. They were building an access road; those mines were in the way. It was clear they didn’t want me there, but I had permission from the governor of the province, so I schmoozed my way through. Of course I didn’t say I was doing a project on child labor; I just told them I was doing a project on small-scale gold mining. You have to be judicious about what you say.

LL: With that in mind, how do you present yourself to the workers and children you’re photographing? Do they get what you’re doing?

LP: The children are easy because they’re curious. It’s a break in their routine: a photographer shows up and it’s a big curiosity. I’d have a troupe of kids around me for a while, then they’d get shooed off by parents, who were worried the kids were bothering me and also wanted them to get back to work. It’s just a matter of patience. I’d study the children carefully and would try to convey certain activities. Then I’d work with a child or two, following their routines. The parents picked up on the fact that I was photographing children more than adults, but I tried to concentrate and didn’t get into long explanations.

LL: How much does it affect you emotionally when you see children in those situations?

LP: It does affect me, for sure. In the Phillipines it wasn’t so bad, because as hard as the kids were working, it seemed like they had plenty to eat and parents around, and I didn’t see tragic situations. Burkina Faso was a bit more desperate. Some kids were running around naked in the hot sun all day long, working hard, and they looked a bit undernourished. The thing that really disturbed me was thinking about them working underground in unsafe conditions. They also work around machines that are pulverizing ore into a flour-like powder, and they sit at the base of these machines, surrounded by torrents of dust and powdered quartz. They’re not using any protection. You can hear this constant refrain of low coughs, and I just know these kids are developing lung ailments and not getting medical treatment. I read about it and then I witnessed it, and that got to me.

LL: You wrote eloquently about these stories for the Philadelphia Inquirer and the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting . What kind of non-visual documentation do you do when you’re there?

LP: I’ve got one those 3×5, 150-page Moleskines in my cargo pocket, and I start a new one each trip. Everything goes down in there: date, time, location, GPS coordinate if possible. On this project, I feel I can do 90 percent visually, but it’s always important to have the scope and texture of narrative to guide viewers along the visual path. I’ve done everything from 1,000-plus word articles to short blog posts and Facebook updates. It was fun to try to post some updates in real time while I was there; I think there’s tons of potential for doing real time journalism like that. At the end of the day I’m a visual journalist, but the operative word is journalist: I’m trying to tell a story.

LL: You’re also doing advocacy through this work, right?

LP: Definitely. I have a point of view, and I’m not making any excuses for that. I’m trying to do this project on a larger, long-term scale; I’ve got several stories in mind. I want to show kids working, but I also want to show the impact of child labor all over the world. There’s a lot of work to do. Right now I’m working in this little sector of gold mining, but there’s human trafficking, the garment industry, fishing… it goes on. I’m thankful I’m in good shape, I have stamina and I can do it.

LL: A lot of people who look at these images will ask, What can I do to remedy this? So, what can they do?

LP: I think the best long-term answer is to try to become an educated consumer. If you’re buying a diamond, there’s a big movement in the diamond industry to have conflict-free diamonds–which is a step in the right direction, but it can also be a bit of a bogus marketing thing. As far as gold goes, I don’t think people should feel guilty about buying it, especially as a lot of gold is recycled. But they can be aware and put pressure on governments and communities to make laws and enforce laws. What can you do? Just be educated. Understand, reach into your conscience. You might not be able to stop kids working if the families are in desperate economic need. But you can give the parents representation, and try to make sure that the kids spend at least part of the day in school. Governments all have their priorities—but not too many governments on the planet really want four-year-old kids working twelve hours a day in the hot sun. I really believe that.

————————————————————————

Visit Larry C. Price’s web site .

Read the article Price wrote for the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Read Price’s article about coal mining in the Phillipines at the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting .

Read Price’s article about coal mining in Burkina Faso at the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting .

Donate to The Child Labor Coalition .

Find out about socially-responsible investing here and here .

8 comments on “ Damaged Goods: An Interview with Larry C. Price ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

It’s very hard to look at these photos, especially as the mother of a six-year old. I hope Price’s photographs bring not only awareness but real change. Great article, Sarah!

Thanks for this, Robin. It has been interesting for me to study Lewis Hine and see that, in his case, slowly chipping away at the problem for many years did lead to real social change. Of course these days we have information overload and compassion fatigue and all that, but I’m hopeful that if great photographers like Larry can continue to do this work, it will eventually have an effect!

Wow. Larry is the real deal. This is such fabulous important work. Heartbreaking photographs.

Indeed, Nick! Hope your photography is going well.

“Damaged Goods” is visual reporting that captivates the viewer and demand attention. “Gold” and “children” are precious words that may work beautifully in the line of a poem, but Larry Price’s pictures and words tell a different reality much closer to the truth.

This shows why we should be thankful for what we’ve got.

Absolutely, Jim! Wish I could make my own kids understand this!

One of the few issues in politics that can be universally condemned regardless of your left/right position and something that breaks my heart as the father of a 12 year old daughter. Great series. I hope it gains a LOT of traction.