Mass Observation

Where is the line between observation and surveillance, between reportage and invasion of privacy? This is one of the old chestnuts of journalism, and it’s especially sensitive in the case of photography, which is by nature more intrusive than the written word. Every photojournalist I’ve ever interviewed has wrestled with ethical dilemmas about when to put the camera down. It’s part of the territory, the most wrenching part of a complex job.

Where is the line between observation and surveillance, between reportage and invasion of privacy? This is one of the old chestnuts of journalism, and it’s especially sensitive in the case of photography, which is by nature more intrusive than the written word. Every photojournalist I’ve ever interviewed has wrestled with ethical dilemmas about when to put the camera down. It’s part of the territory, the most wrenching part of a complex job.

So it was fascinating to see, on the first week of my annual visit to London, the just-opened show Mass Observation at the Photographers Gallery . Founded in the 1930s, Mass Observation was an organization that aimed to record the texture of life in Britain in exhaustive detail. Unfortunately named to imply a creepy, Big Brother-ish surveillance state, Mass Observation was essentially well meaning and more haphazard than the name implies. And along with the material it collected, the organization’s own story is an intriguing reflection of British social history.

According to its founders, the Mass Observation project aimed to “put ordinary people on the map.” To wit, a rather bizarre list of priority issues in the organization’s first manifesto includes “behavior of people at war memorials,” “the private lives of midwives” and the all-important “distribution, diffusion and significance of the dirty joke.” No detail was too small. One observer, documenting sexual activity on the beach in Blackpool in 1937, wrote: “She rises from form, tightens her girdle. He presses her breast, drawing her down. They cuddle. He does not kiss her.”

According to its founders, the Mass Observation project aimed to “put ordinary people on the map.” To wit, a rather bizarre list of priority issues in the organization’s first manifesto includes “behavior of people at war memorials,” “the private lives of midwives” and the all-important “distribution, diffusion and significance of the dirty joke.” No detail was too small. One observer, documenting sexual activity on the beach in Blackpool in 1937, wrote: “She rises from form, tightens her girdle. He presses her breast, drawing her down. They cuddle. He does not kiss her.”

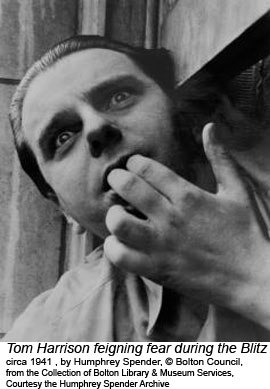

Unlike the federally-funded arts and reportage projects happening in the United States in the 1930s, Mass Observation began as a private initiative. The brain trust behind it belonged to Tom Harrisson, a brigadier-general in the British Army, and Charles Madge, a poet. Members of the privileged upper middle class, Harrisson and Madge were united by their wish to overcome the hidebound British class system. “We were going to make the world a better place,” says Madge in the fascinating 1985 documentary

Stranger Than Fiction

, shown at the end of the exhibition.

Unlike the federally-funded arts and reportage projects happening in the United States in the 1930s, Mass Observation began as a private initiative. The brain trust behind it belonged to Tom Harrisson, a brigadier-general in the British Army, and Charles Madge, a poet. Members of the privileged upper middle class, Harrisson and Madge were united by their wish to overcome the hidebound British class system. “We were going to make the world a better place,” says Madge in the fascinating 1985 documentary

Stranger Than Fiction

, shown at the end of the exhibition.

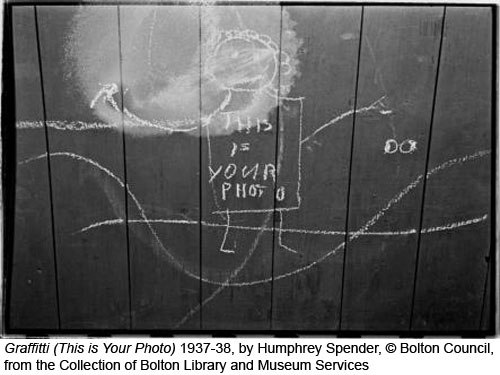

So far so good, right? Well… maybe. But Harrisson and Madge had no interest in recording the texture of life among the middle and upper classes—that was too familiar. As with the American federal arts projects of the 1930s, this was largely a case of well-meaning, middle-class liberals descending upon the poor and imposing themselves. “The material… was going to remain uncollected unless we did it,” Madge says in the documentary: fair enough. But as the photographer Humphrey Spender notes, “we were called spies, pryers, mass-eavesdroppers, nosey parkers, peeping toms, lopers, snoopers, envelope-steamers, keyhole artists, sex maniacs, sissies, society playboys.” And that was just by their mothers! (Joke.)

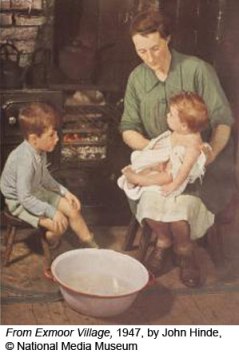

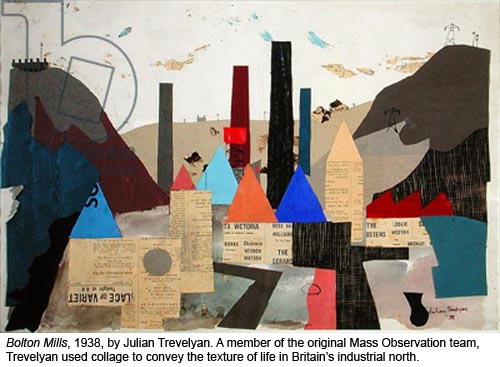

And so, we have what my British compatriots would call a sticky wicket: while there’s certainly an element of voyeurism and condescension in the nature of MO’s work, it also yielded a rich and fascinating body of information. Apparently a very forceful individual, Harrisson put together an impressive early task force that included photographer Spender, artist Julian Trevelyan and documentary filmmaker Humphrey Jennings. These men were all curious, visually astute and very committed. Spender’s images from the working-class town of Bolton, collected in the book Worktown People: Photographs from England 1937-38 , are a treasure trove of documentary imagery that could sit alongside the work of Walker Evans or Dorothea Lange.

“I believed obsessively that the truth would be revealed only when people were not aware of being photographed,” Spender notes in a wall text. “I had to be invisible. There was an uncomfortable element of spying in all this.”

In addition to its main documenters, Mass Observation also used a self-selecting pool of volunteers to gather information. Volunteers needed no training, simply time and enthusiasm for the task at hand—which perhaps wasn’t difficult since an early focus of the organization was British pub life. In 1943, Harrisson published some of this information in a book called The Pub and the People .

It was around that time that Mass Observation lost its innocence. During the Second World War, the Ministry of Information became interested in the kind of man-on-the-street data MO could collect. Among other things, it commissioned a survey on why Londoners weren’t using rickety, unsafe street shelters during bomb raids. Armed with data on the public’s fears, the Ministry responded with a massive propaganda campaign urging the public to use the “safe” shelters. Understandably, this created some bitterness among the earnest MO observers who’d conducted the survey and knew the shelters couldn’t sustain a direct hit.

It was around that time that Mass Observation lost its innocence. During the Second World War, the Ministry of Information became interested in the kind of man-on-the-street data MO could collect. Among other things, it commissioned a survey on why Londoners weren’t using rickety, unsafe street shelters during bomb raids. Armed with data on the public’s fears, the Ministry responded with a massive propaganda campaign urging the public to use the “safe” shelters. Understandably, this created some bitterness among the earnest MO observers who’d conducted the survey and knew the shelters couldn’t sustain a direct hit.

In the years after the war, Harrisson was faced with a choice: to take Mass Observation in an academic or commercial direction. With the distrust of academia typical among the British professions, he chose the latter course—no doubt with some reluctance. Thus began a journey that resulted, in 1949, in the project’s incorporation as a private market research firm. And so the transformation was complete: an organization that had started with the idealistic wish to unite social classes morphed into a tool of people wanting to manipulate a gullible public.

The story doesn’t end there, though. In 1981, something like the original Mass Observation was relaunched at the University of Sussex, where the organization’s archives are stored. In tune with our social media times, the new Mass Observation is a first-person project, inviting observers to submit thoughts on projects ranging from their gardening (and the effect of glitzy gardening TV shows on the gardener’s psyche) to their relationship with photography. Some of these records are shown in the second half of the exhibition.

Harrisson and Madge, who drifted away from the project after its commercialization in the 1940s, came back together in 1960, reuniting many of the original team to produce a book called

Britain Revisited

. Lacking some of the spontaneity of the earlier work, this project is still a good example of documentary journalism. There are wonderful photographs by Michael Wickham of holidaymakers in Blackpool, and fine drawings by Julian Trevelyan and Humphrey Spender.

Harrisson and Madge, who drifted away from the project after its commercialization in the 1940s, came back together in 1960, reuniting many of the original team to produce a book called

Britain Revisited

. Lacking some of the spontaneity of the earlier work, this project is still a good example of documentary journalism. There are wonderful photographs by Michael Wickham of holidaymakers in Blackpool, and fine drawings by Julian Trevelyan and Humphrey Spender.

And so, if Mass Observation is a cautionary tale of social idealism corrupted by government and commercial interests, it also offers hope that what’s worthy in such a project can survive. Though the current work of Mass Observation might seem superfluous in this age of mass blogging, it does, perhaps, offer something valuable: thematic curation, a range of voices, and a link to a more innocent past.

One comment on “ Mass Observation ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Great article Sarah. I enjoyed it a lot. It was very interesting to read how MO evolved from being a rather amateurish, paternalistic attempt at deciphering the goings-on of the lower orders into something a bit more manipulative and sinister later on.