Photography meets Theater in Chimerica

When does a news photograph become iconic? Typically, when it distils an important story into a single, powerfully graphic image. Its subjects are often victims of injustice—Nick Ut’s

napalmed Vietnamese girl running along the road

, Kevin Carter’s

emaciated African child being stalked by a vulture

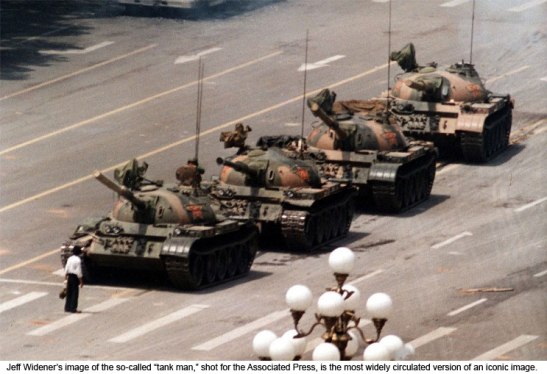

—but occasionally, the camera records a moment of heroism. That was the case with “tank man,” the notorious photograph of the young man who stood in front of a line of tanks in Tiananmen Square in 1989, symbolically taking on the might of the Chinese army.

When does a news photograph become iconic? Typically, when it distils an important story into a single, powerfully graphic image. Its subjects are often victims of injustice—Nick Ut’s

napalmed Vietnamese girl running along the road

, Kevin Carter’s

emaciated African child being stalked by a vulture

—but occasionally, the camera records a moment of heroism. That was the case with “tank man,” the notorious photograph of the young man who stood in front of a line of tanks in Tiananmen Square in 1989, symbolically taking on the might of the Chinese army.

This photograph, visible on a thousand student dorm wall posters in the 1990s, is now at the center of Chimerica , a play I saw in my second week in London. Written by the talented young playwright Lucy Kirkwood, Chimerica features an American photojournalist, a Chinese former activist and other characters whose relationships reflect the tangled dependencies of China and America. Heavy on politics, the play nevertheless manages to be heartfelt and affecting. I loved it, and hope it transfers to Broadway despite its conspicuous lack of flying superheroes and musical numbers.

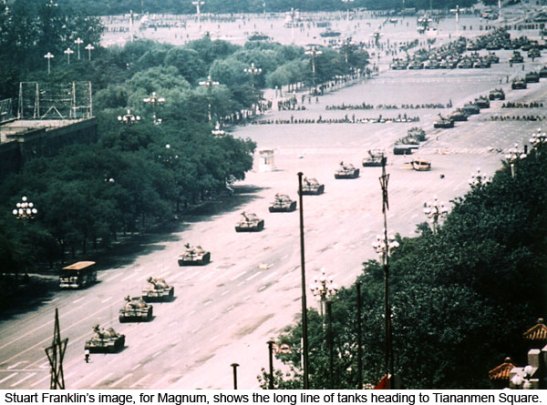

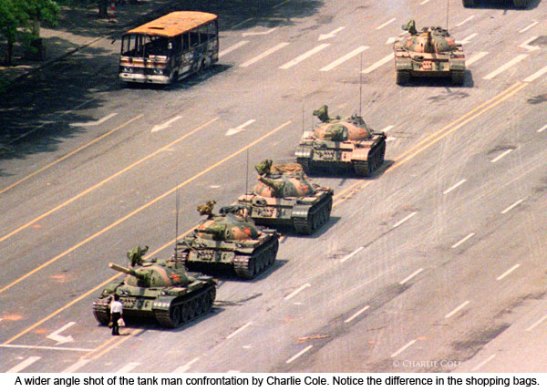

As Kirkwood points out in an author’s note, she felt at liberty to base her play on the photograph because at least six versions of it, taken by different photographers, exist in common currency. The photographers who shot the “tank man” were staying in the Beijing Hotel, overlooking Tiananmen Square. The most famous image of the scene was shot by Associated Press photographer Jeff Widener, but Magnum photographer Stuart Franklin and Reuters photographer Arthur Tsang Hin Wah were among the photographers who took others (for interesting stories about the different versions, see here and here ).

Kirkwood creates a photographer, Joe Schofield, who isn’t based on any of these men but could plausibly be one of them. Carried to China in 1989 by his wanderlust, eighteen-year-old Joe gets more than he bargained for when he witnesses the Chinese government killing student protestors, then sees the tank man from his hotel window on Tiananmen Square. Joe takes out his camera and, “spraying and praying,” manages to capture an iconic shot and hide the film before Chinese soldiers rush his room and confiscate the camera.

When we meet Joe again twenty-three years later, he’s surrounded by a grab-bag of interesting characters that include his friend Zhang Lin, a former student activist at Tiananmen, and Tess, a British market researcher tasked with creating a profile of the average Chinese consumer. Back in China to do a story about workers at a plastics factory, Joe wonders what happened to the hope and heroism represented by “tank man.” Curious, he decides to try and find his former subject and see what “one of the great heroes of twentieth century history” thinks about the tawdry new China.

What happens to the subjects of iconic photographs, how does the iconic image affect their later life? This is a subject that has been explored before, both in literature and real life. In Arturo Perez-Reverte’s The Painter of Battles , an angry subject comes to find a reclusive former war photographer, intent on killing him. In Marisa Silver’s Mary Coin , we find out about the hardscrabble life of a woman based on Florence Owens Thompson, the famous subject of Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother .

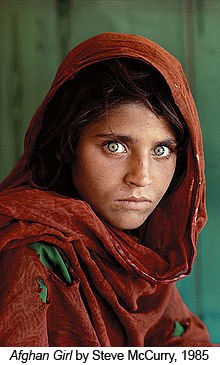

In reality, such stories are usually more heart-warming. Kim Phuc, the infamous “Napalm Girl,” used her fame to establish a foundation helping child victims of war, and is a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador. Sharbat Gula, the woman in Steve McCurry’s famous 1985

Afghan Girl

, was

rediscovered and rephotographed

by the photographer in 2002 living a simple life in the mountains. Their reunion was “quiet,” according to National Geographic writer Cathy Newman.

In reality, such stories are usually more heart-warming. Kim Phuc, the infamous “Napalm Girl,” used her fame to establish a foundation helping child victims of war, and is a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador. Sharbat Gula, the woman in Steve McCurry’s famous 1985

Afghan Girl

, was

rediscovered and rephotographed

by the photographer in 2002 living a simple life in the mountains. Their reunion was “quiet,” according to National Geographic writer Cathy Newman.

In Chimerica , the quest to find “tank man” is its own tortured journey, taking Joe through the Chinese underworld, from a sleazy Garment District strip club to a Chinatown fish shop that’s a front for an illegal immigration network. The mystery of the tank man’s identity drives the drama, but the quest, and the characters it turns up, gives Kirkwood the chance to reflect on deeper issues. Is the cost of China’s rapid development too high? Is idealism even possible any more? Is America, as Zhang Lin suggests to Joe, “fucked”?

Such questions can’t be answered, of course, but merely asking them is bracing—and Kirkwood’s play is so nimble that it never comes across as showy or didactic. Watching Chimerica , I couldn’t help thinking about how theater in England often seems more ambitious than its American counterpart. There’s a new crop of young, talented playwrights (many of them women ) whose work is taking on big, ambitious subjects, from financial scandals to sex trafficking to the British class system. Maybe it’s because they get more support, or because there’s a rich tradition of politically-engaged theater in Britain, or both, but whatever the reason, it’s a great thing.

In addition to the big questions she tackles, Kirkwood also takes on a small one: what was in the shopping bags the tank man was carrying in the photo? As Joe’s reporter friend Mel says, “it’s the detail, it’s the human interest, the small intimacies of great souls” that make a story—or an image—compelling.

“Why is everyone so hung up on that, what he bought from the store that morning?” Joe wonders to Tess, and she replies, “Because I think that’s amazing. A man goes out to buy a paper, or a new shirt or something, and by the end of the day, he’s part of history.” More pretentiously, in Sausurrean terms the shopping bags are a signifier, showing us that the tank man is not a self-appointed martyr but just an ordinary Joe, returning from an errand.

When we do, finally, find out the content of those bags, it is unexpected and lends the image a new, tragic weight. Though it may not be literally true, the poignant answer fits perfectly in the puzzle pieces of Kirkwood’s ambitious, stimulating play.

6 comments on “ Photography meets Theater in Chimerica ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Terrific article, Sarah!

Sarah, as usual, I’ve been pondering your latest essay for a couple of days of introspective mulling the right response. Your essays are always so nuanced, graceful and insightful that they often propel me onto my own pontificating tangents never to return.

This time it’s mostly consisted of an inner monologue on not just the courage of the ‘tank man’ but also his ability to preserve a Salingeresque anonymity. No doubt abetted by the ‘People’s Republic.’

When the tank man made his courageous stand I was a sensitive 17-year-old private in the US Army. Widener’s cautionary image left a deep existential brand on my character. That image imparted a treatise on the awesome powers and limitations of the lone wo/man and of the mighty government.

Anyway, I was spiraling on the brink of never-returning (or commenting) when making my morning news rounds yesterday I experienced deja vu: http://tinyurl.com/kl7vyae

Tianimen redux. History never stops repeating. What apparition is this generation’s Tank Man?

Thanks so much for this, Vern. How chilling to see history degrading as it repeats. I will share this link on The Literate Lens’ Facebook page.

A great piece of writing about the ripples an iconic image can have through the decades. The contrast between this confrontation between overwhelming military power and a lone everyman (with the shopping) makes this image so powerful. I suppose it also meshes with ideas surrounding individualism in the developed West, which I think also adds another layer to our response to this image.

Dear Sarah,

I have just read and enjoyed the latest Literate Lens.

I had not seen the wide-angle Stuart Franklin image of “Tank man” before. It has reminded me of a question which came to me on first seeing the Jeff Widener photo, namely why did the following tanks not sweep around the blocked tank, and continue their progress across the Square of Heavenly Peace?

Was the Army also trying to set up an image of might versus minuscule man, or “Resistance is useless”?

Just because I’m a conspiracy theorist, it does not mean they’re not after me.

Yours and GCHQ’s,

Michael

Thanks for your comment, Michael! The “resistance is futile” idea is interesting, and one I hadn’t thought of before. But there could be several other reasons the tanks didn’t sweep around the lead tank, as follows:

1. The tank drivers were terrified to do anything “off script” and were waiting for orders from their commanders, which took a long time to come, by which time “tank man” had disappeared into the crowd;

2. The drivers communicated with HQ, but the commanders did not know how to deal with this situation, felt that breaking formation could cause mess and chaos, and were well aware that the world’s media was watching;

3. The lead tank driver had some sympathy with tank man’s cause.

In ‘Chimerica,’ the playwright came up with an interesting story for the lead tank driver as well as for tank man. But I won’t give it away.

In any case, if your supposition is right, it certainly backfired on the Chinese!

All best,

Sarah