A Hard Softness: Julia Margaret Cameron and Afterimage

The new

Julia Margaret Cameron show at the Metropolitan Museum

is everything Cameron herself was not: small, orderly, and understated. Yet it’s far from being a trifle. Even in a modest setting, the intensity and sensuality of Cameron’s photographs burst through. The images, which combine Victorian preoccupations with a shockingly modern aesthetic, have a life force that can’t be denied.

The new

Julia Margaret Cameron show at the Metropolitan Museum

is everything Cameron herself was not: small, orderly, and understated. Yet it’s far from being a trifle. Even in a modest setting, the intensity and sensuality of Cameron’s photographs burst through. The images, which combine Victorian preoccupations with a shockingly modern aesthetic, have a life force that can’t be denied.

Unlike other wealthy Victorian ladies who took up photography as a lark, producing sentimental pictures of flowers and children, Cameron was a true original. Shaped by a colorful background, she was born in Calcutta in 1815 to a British father and a French mother, and was raised eating curry and speaking Hindustani. Not considered a beauty like her six sisters, she nevertheless caught the eye of Charles Hay Cameron, an eligible lawyer twenty years her senior, who must have been attracted to her wit and spirit.

Cameron only discovered photography at the age of forty-eight. Before that, she was a woman of causes and tireless energy. Living in Calcutta in the 1840s, she raised fourteen thousand pounds (around half a million dollars in today’s money) to send to victims of the Irish potato famine. She was generous, showering her children and friends with endless attention and gifts, writing letter after letter when away from them. And she was accustomed to getting her way. The poet Alfred Lord Tennyson, her friend and portrait subject, was once presented with thirty rolls of wallpaper by Cameron: the aim was to replace the wallpaper in his house that

she

didn’t like.

Cameron only discovered photography at the age of forty-eight. Before that, she was a woman of causes and tireless energy. Living in Calcutta in the 1840s, she raised fourteen thousand pounds (around half a million dollars in today’s money) to send to victims of the Irish potato famine. She was generous, showering her children and friends with endless attention and gifts, writing letter after letter when away from them. And she was accustomed to getting her way. The poet Alfred Lord Tennyson, her friend and portrait subject, was once presented with thirty rolls of wallpaper by Cameron: the aim was to replace the wallpaper in his house that

she

didn’t like.

What would such a formidable lady do with a camera? Her oldest daughter Julia must have wondered, because she presented her mother with a camera in 1863. From the start, Cameron’s images were striking. Unconcerned with flattery, she created craggy, real portraits of famous men like Tennyson and her neighbor, the scientist Sir John Herschel. Friends and family members were pressed into service to pose as historical and allegorical figures, and children were portrayed with a refreshing lack of sentimentality.

What would such a formidable lady do with a camera? Her oldest daughter Julia must have wondered, because she presented her mother with a camera in 1863. From the start, Cameron’s images were striking. Unconcerned with flattery, she created craggy, real portraits of famous men like Tennyson and her neighbor, the scientist Sir John Herschel. Friends and family members were pressed into service to pose as historical and allegorical figures, and children were portrayed with a refreshing lack of sentimentality.

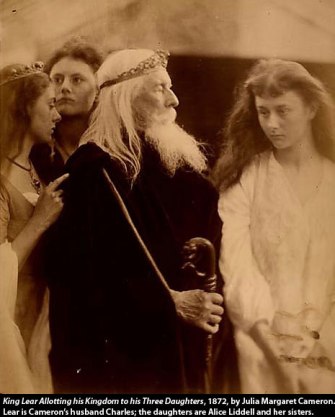

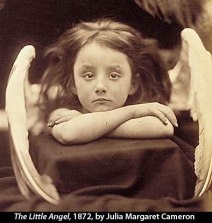

Compare, for example, this image of a girl by Charles Dodgson (better known as Lewis Carroll, who was Cameron’s friend and neighbor on the Isle of Wight) with an image of a child by Cameron. Though she sometimes photographed children as angels, Cameron knew better than to idealize them. Even her angels and putti were individuals, complex in their needs and desires.

In the 1860s, photography was still in its infancy. It must have been an exciting time to be working—analagous, in a way, to today’s digital age. Questions were rife: Could photography aspire to the status of art? What must it do to be admitted as such? Could a woman photographer-artist be taken seriously?

Faced with these questions, Cameron sallied forth with typical confidence. Criticism didn’t deter her. The most frequent criticism, of course, concerned her persistent use of soft focus. “Mrs. Cameron exhibits her series of out-of-focus portraits of celebrities,” the

Photographic Journal

sneered in 1864, but Cameron paid no heed. To her mind, softened focus lent the image richness and immediacy. As Anthony Lane wrote recently in

a very informative

New Yorker

article

, “Time does not freeze in such a photograph. It melts and steams.”

Faced with these questions, Cameron sallied forth with typical confidence. Criticism didn’t deter her. The most frequent criticism, of course, concerned her persistent use of soft focus. “Mrs. Cameron exhibits her series of out-of-focus portraits of celebrities,” the

Photographic Journal

sneered in 1864, but Cameron paid no heed. To her mind, softened focus lent the image richness and immediacy. As Anthony Lane wrote recently in

a very informative

New Yorker

article

, “Time does not freeze in such a photograph. It melts and steams.”

This brings me to one of my favorite ever historical novels, Helen Humphreys’ Afterimage . Inspired by Cameron’s work, Afterimage also melts and steams, bringing the power of narrative to bear on Cameron’s fascinating life and work. The novel tells the story of Annie Phelan, an Irish maid whose world expands vastly when she’s hired by the eccentric artist Isabelle Dashell. Dashell is loosely based on Cameron, though her biographical details are changed: she has no children, for one thing, so channels her frustration and creative force into art.

There are many things to love about Humphreys’ novel; I’ll just mention a few. First, it examines the issue of class boundaries in Victorian England in a way that is devastating but also fleet-footed. The relationship between the mistress and her maid/model/muse is delicately drawn: it can’t help but change when Annie starts posing for Isabelle, but it does so in surprising and interesting ways. In poetic prose, Humphreys captures the feelings that must have been roiling under the surface when Mary Hillier, Cameron’s maid, posed for images like this one of the Madonna.

There are many things to love about Humphreys’ novel; I’ll just mention a few. First, it examines the issue of class boundaries in Victorian England in a way that is devastating but also fleet-footed. The relationship between the mistress and her maid/model/muse is delicately drawn: it can’t help but change when Annie starts posing for Isabelle, but it does so in surprising and interesting ways. In poetic prose, Humphreys captures the feelings that must have been roiling under the surface when Mary Hillier, Cameron’s maid, posed for images like this one of the Madonna.

Second, Humphreys brings some delicious humor to her novel. Before reading it, I’d never considered the complicated logistics of Cameron’s work: the challenge of taking banal materials and transforming them into the stuff of art. But then I read this passage:

Wilks, the gardener, is standing at the far end of the studio. He is dressed in what looks like a tablecloth, pinned at his throat so that it becomes a cape. On his head is a rough sort of crown made from painted cardboard. On his legs, breeches. On his feet, boots. Tess is lying on her stomach on the floor in front of him, clutching on to his ankle. Her hair is loose and washes out from her head like seaweed, matted and wild. She is wrapped in a sheet.

“You’re not trying to trip him up,” says Isabelle, circling them madly. “You’re begging him for forgiveness, begging him to take you back.”

“You’re not trying to trip him up,” says Isabelle, circling them madly. “You’re begging him for forgiveness, begging him to take you back.”

…”Don’t,” says Wilks irritably.

“What?” says Isabelle.

“She’s cutting off my circulation.” Wilks shakes his leg as though Tess is a pesky dog he’s trying to dislodge.

…”Who are they meant to be, ma’am?” Annie asks, stepping forward into the room.

Isabelle looks at Annie for a moment before answering. “Guinevere,” she says, pointing to Tess. “King Arthur.”

But although the novel is infused with lighter moments like this one, it is also deeply serious and genuinely moving. Humphreys gives equal weight to Isabelle and Annie, investing both of them with complicated desires and fierce intelligence. In the end, Annie’s longing to transcend the drudgery of her servant’s life merges with Isabelle’s need to create beauty and meaning through art, and a collaboration is born.

The result of this collaboration—as in Cameron’s work—is a set of images that are delicate but forceful, frank. Ahead of their time, they challenge our preconceptions and stereotypes. Novels being what they are, the Isabelle Dashell character in

Afterimage

is a somewhat tragic figure, often tortured by doubt. It’s nice to know that Julia Margaret Cameron, equally driven and criticized, didn’t know the meaning of the word.

The result of this collaboration—as in Cameron’s work—is a set of images that are delicate but forceful, frank. Ahead of their time, they challenge our preconceptions and stereotypes. Novels being what they are, the Isabelle Dashell character in

Afterimage

is a somewhat tragic figure, often tortured by doubt. It’s nice to know that Julia Margaret Cameron, equally driven and criticized, didn’t know the meaning of the word.

———————————————————————————

Julia Margaret Cameron is on display at the Metropolitan Museum through January 5, 2014. For opening hours and admission details, click here .

6 comments on “ A Hard Softness: Julia Margaret Cameron and Afterimage ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Wonderfully written and very interesting – I love the photographs their honesty as well as the softness of focus – may come over to see exhibition in Jan! lots of love xxxx Jo

Please do! But it’ll have to be early Jan — it closes on Jan. 5.

I thought it opened on 5/1 so lucky you mentioned that! When does it open? Xx

It opened last month and is up until Jan. 5.

Very interesting, Sarah, it sounds like a great exhibition. Many thanks for pointing me towards “Afterimage”, which I must read.

Next time you’re in Britain, I recommend a visit to the Julia Cameron museum on the Isle of Wight (see http://www.dimbola.co.uk ). This was where she lived and did much of her photography, using servants and neighbours as models, and experimenting with new chemicals in an outhouse. The class divergence used by Helen Humphreys is illustrated as is the breadth of Cameron’s cultured neighbours. There is a reconstruction of her bedroom, including reproduction William Morris wallpaper – I wonder if she over-ordered and gave the surplus to Tennyson?!

Looking forward to your next Literate Lens,

Michael

I would love to go to Dimbola!