Identity Politics: an interview with Paolo Woods

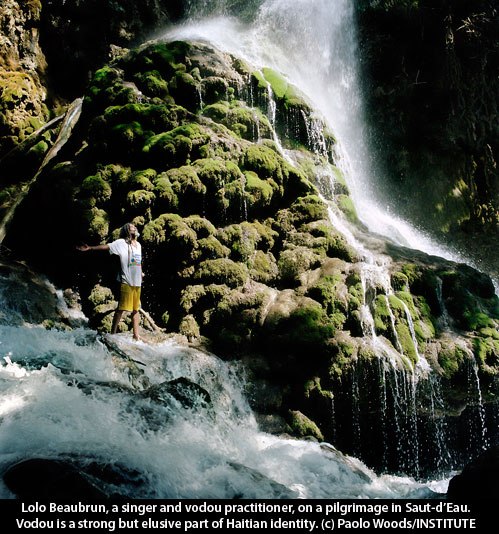

Think of Haiti, and chances are, one of a few images will spring to mind. The earthquake of 2010, with its grisly death toll and survivors living in makeshift tent cities. The exotic mysticism of vodou, full of primitivist objects and colorful rituals. The father-son dictators François “Papa Doc” Duvalier and Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, who, for over three decades, lived in the lap of luxury while terrorizing their citizens.

Think of Haiti, and chances are, one of a few images will spring to mind. The earthquake of 2010, with its grisly death toll and survivors living in makeshift tent cities. The exotic mysticism of vodou, full of primitivist objects and colorful rituals. The father-son dictators François “Papa Doc” Duvalier and Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, who, for over three decades, lived in the lap of luxury while terrorizing their citizens.

Paolo Woods wants us to see a different Haiti. A Dutch-born, Italian-raised photographer who has lived in Haiti since 2010, Woods is the antithesis of what he calls the “misery journalist.” Instead of just reacting to the news cycle, he prefers to steep himself in a story, slowly uncovering its complexity. His interest in individuals is balanced by a fascination in systems—of law, government, business—and how they interact.

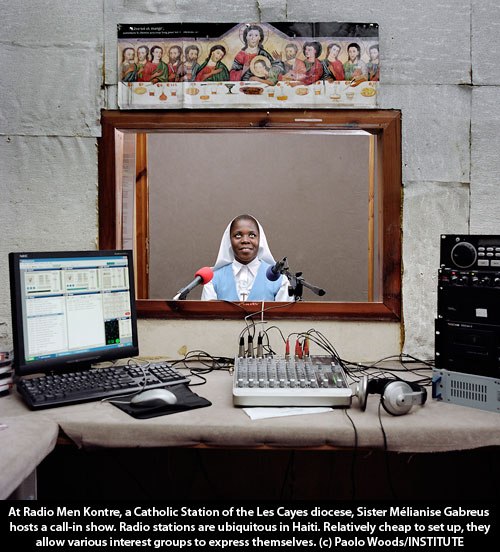

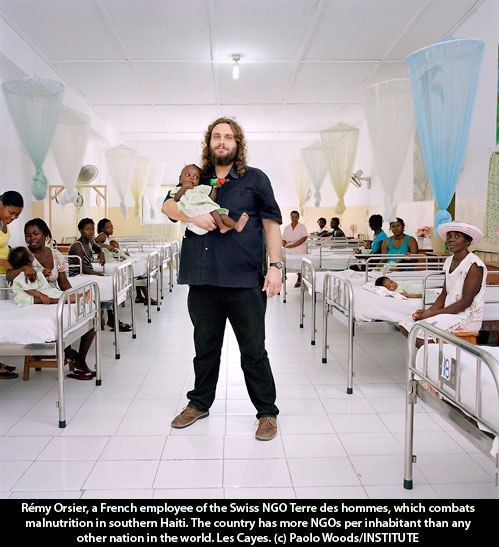

State , Woods’ new book (co-authored with writer Arnaud Robert) is a revelation. Instead of looking at Haiti as a nation of victims, Woods and Robert examine the infrastructures that are successful in Haiti, from religion to entrepreneurism to the ubiquitous small radio stations that give people a voice. They raise questions of whether outside aid helps or hurts the country, and wonder how a nation-state can build itself from the ground up.

The work follows on from previous projects in which Woods has sought to uncover national identities and push beyond stereotypes. Whether he’s photographing a female dentist in Iran or a Chinese entrepreneur in Nigeria, his images eschew drama in favor of deep engagement. He takes his time, researching and examining a story from different angles. In the words of Dany Laferriere, the Haitian-Canadian author who writes an introduction to

State

, “you need time to cook a dish like this one.”

The work follows on from previous projects in which Woods has sought to uncover national identities and push beyond stereotypes. Whether he’s photographing a female dentist in Iran or a Chinese entrepreneur in Nigeria, his images eschew drama in favor of deep engagement. He takes his time, researching and examining a story from different angles. In the words of Dany Laferriere, the Haitian-Canadian author who writes an introduction to

State

, “you need time to cook a dish like this one.”

Two weeks ago, at an evening screening at Photoville , Woods came across as a thoughtful man who pursues his subject with rigor, but at the same time keeps an open mind. The authenticity of his work was evident, as was Woods’ feeling that a complete story usually needs to be told in both images and words.

Back home in Les Cayes, Haiti, Woods graciously made time this week to talk about photographing the Haitian elite, the role of outsiders in development, and the intrinsic human desire for order.

Literate Lens: When did you first start to get interested in the idea of statehood?

Paolo Woods: It’s something I’ve always been interested in. I grew up in Italy, with a Dutch mother and Canadian father, so my national identity was always questionable. Very early on, issues of national identity were interesting to me, and my father was a professor teaching state-church relationships, so this was something we talked about a lot at home. How much does the individual define himself by nationality? How do institutions like the church interact with the state? And how much does a state working, or not working, influence national identities?

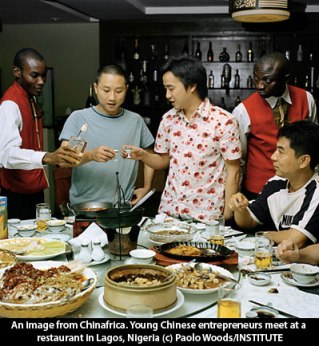

LL: A previous project of yours, Chinafrica, examined the phenomenon of Chinese businesses in Africa, and the resulting culture clash. Was that an important precursor to the Haiti work?

LL: A previous project of yours, Chinafrica, examined the phenomenon of Chinese businesses in Africa, and the resulting culture clash. Was that an important precursor to the Haiti work?

PW: Yes, absolutely. The reference point for this kind of incursion into a continent is colonialism, but the reason the Chinese are in Africa is by no means to spread their ideology or teach Chinese customs. It’s absolutely market-driven. And it’s a game changer. China is there because it wants Africa’s natural resources and new clients, and thanks to its presence, many Africans can now afford cheap Chinese goods. This is not an easy story to translate in images: you get very little access to the Chinese in Africa, but it was an important story for me visually. We have two images of Africa–one is the National Geographic image of lions in a beautiful park, the other is the misery Africa, with people dying. The Chinafrica story shows something different, a more normal Africa, a place now in the throes of a marriage of convenience where each partner is somewhat suspicious and there’s deep racism on both sides. It’s a good metaphor for the globalization of relationships and clash of national identities.

LL: How did you get from there to Haiti, intellectually?

PW: My first idea was to compare a failed state like Somalia with a successful state like Switzerland. But Somalia wasn’t an option at the time, it was too violent, and I wasn’t interested in doing war photography. The second option was Haiti, which was actually more interesting to me because the Haitian identity is unique and very strong, and, combined with a very deficient state, it became a great observation point for what I wanted to analyze.

LL: What were your preconceptions of Haiti before you moved there?

PW: More or less the ones everyone has, I think. In my early twenties, I came to Haiti on vacation–which sounds kind of weird, but I’d read about the country and thought it sounded interesting. I think certain images of Haiti are true: it’s a very poor country, mostly black, where vodou plays a big role. But to reduce the country to these things is to make a shallow stereotype–as if you told me that Italy is all about pizza, pasta and tarantella. With Haiti, the stereotypes have been repeated so many times that they seem almost irrefutable, and I found that reductive.

LL: A lot of outsiders have come in to Haiti, imposing values and offering change. How did you go in as an outsider and gain the kind of trust you needed to do this work?

PW: I think the thing was, I wasn’t coming there to change their lives, to convert them to another religion, or to tell them my model was better. I was basically coming there to learn, and I didn’t have a year’s budget I had to spend before November 15th, which is a big issue for NGOs. So I didn’t have this attraction of being somebody who could be milked, or the suspicious aura of someone who wants to use people for his own purposes. There’s a certain kind of trust that’s created when you’re on the same level as other people–though obviously I wasn’t completely on the same level, because I had different buying power, and that’s something people never forget.

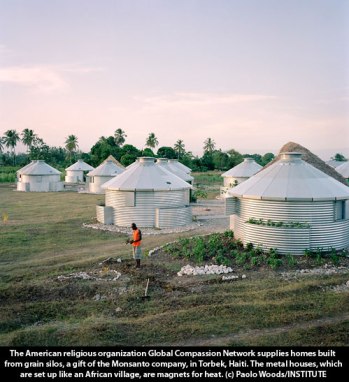

LL: You’re fairly critical of NGOs throughout the book…

PW: It’s a big issue, so let me try to break it down. I absolutely think there’s a role for NGOs in a crisis like an earthquake, a cholera outbreak, or a war. NGOs do some amazing work. But their role in development is more problematic. In the last forty or fifty years, we’ve seen NGOs doing development in Africa and Southeast Asia, and it’s been proven that the model is faulty. Why? Because the NGO follows the money, usually from an institutional donor, and comes in for a set time with a set budget. You don’t resolve a gigantic issue like that. I’ve seen hundreds of examples of beautiful NGO projects that are inaugurated with glossy ribbon-cutting ceremonies, and just six months later, the place is abandoned because nobody has paid the electric bill or bought gas for the generator, or because there’s no system in place to continue. If you want something to work, you usually have to have either a private entrepreneur or a cooperative.

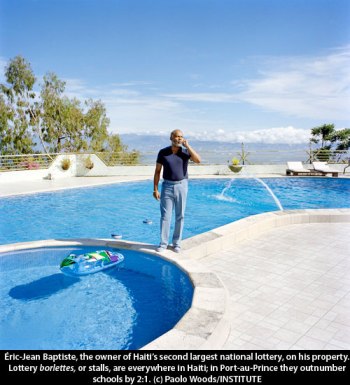

LL: But entrepreneurs can be good or bad, too. You did a story about Haitian entrepreneurs and elites that caused a lot of controversy when it was published there. Can you talk about that?

LL: But entrepreneurs can be good or bad, too. You did a story about Haitian entrepreneurs and elites that caused a lot of controversy when it was published there. Can you talk about that?

PW: Everyone knows who these people are in Haiti, but they’d never really been seen in their natural environments. When Arnaud and I decided to do the story, it was difficult to gain access. We told people the truth, that we wanted to talk about the Haitian elite, and some people allowed us into their homes. Some asked for prints, and I’d send them, and they liked the images. But when the article came out, there was a strong negative reaction from some of the people we interviewed and photographed: suddenly, they saw themselves from the outside and realized how entitled they looked. If you read the article, I don’t think it’s biased: I personally think a strong entrepreneurial class is one of the things that will get Haiti back on its feet. But countries tend to get the elites they deserve, and although there are some doing good work in Haiti, others are exploitative. The story stirred up a lot of deep feelings, and Arnaud and I started getting angry calls and violent threats, but also a lot of compliments from all the other Haitians.

LL: In a lot of the images of elites, the wealthy people are light-skinned and there are often black servants in the background. I couldn’t help feeling that these people weren’t aware of how they were presenting themselves.

LL: In a lot of the images of elites, the wealthy people are light-skinned and there are often black servants in the background. I couldn’t help feeling that these people weren’t aware of how they were presenting themselves.

PW: Well, it’s in the eye of the beholder. I have black people working for me at home—if you came to my house tomorrow and took a photo, you could probably show me in a way that might look unflattering. So what’s the issue? Is it bad to have a black employee in a country where eighty percent of population is black? Not really: the issue is the relationship. I tried to play a bit with the stereotype of master and servant, and to push beyond it. I wanted to do images that did not scream “Haiti” as soon as you see them. Many of the photographs I did of the elite could have been taken in other countries and wouldn’t have shocked as they do here, given the subject of slavery is always present in people’s mind’s in Haiti. There are different ways of reading these images.

LL: At the other end of the spectrum, you photographed poor people in Canaan, an informal settlement that sprung up after the 2010 earthquake. People there are trying to organize and introduce government. Can you talk about that?

PW: When the earthquake happened, people feared a tsunami so they climbed up into the hills and started living in Canaan, claiming parcels of land for themselves. Since then, groups of people have tried to organize the place. On the surface, it looks like just another slum, but a lot of people there regard it with pride and want to build up a civic structure. This was revealing: it suggested to us that Haitian people desire order and governance, not anarchy, which is often thought to be the case.

LL: Your book has a lot more text than the average photography book. You worked with Arnaud Robert, a writer-journalist with a long experience of being in Haiti. Why was the text so important to you?

LL: Your book has a lot more text than the average photography book. You worked with Arnaud Robert, a writer-journalist with a long experience of being in Haiti. Why was the text so important to you?

PW: This is something I feel passionate about. Photography cannot live on its own. Images are striking, intriguing, powerful, mysterious, and they need words to fill out the context. We live in a period where the press is not doing well, and a lot of documentary photographers are turning toward the art world. That’s fine, it can be beautiful, but in that world texts are often unwelcome; it’s thought that you’re explaining too much. I do not think that is the case. Text can make available the different layers of an image to a viewer without being pedagogic. I’ve always worked with writers. Arnaud came to Haiti ten years ago as a music journalist, so he had a completely different point of view than someone who’d come to do misery journalism. We had a similar approach on how to construct a story, how text and images should play together, and what kinds of stories we wanted to do.

LL: What have you learned about statehood in doing this project?

PW: Before studying Haiti, I mostly thought as statehood as something that comes from the top down—like when Napoleon centralized France and created a series of laws that incarnated the state. Haiti gave me a sense of the opposite force, a push and desire for state. People do have a shared identity, a shared DNA that they want to recognize in this grey area between nation and state. It has been continuously betrayed in this country, and yet it remains extremely alive.

————————————————————————

Paolo Woods is represented by INSTITUTE. See his artist page here .

Images from State are on exhibit at the Musée de l’Elysée in Lausanne, Switzerland, until January 5th, 2014.

The New York Times Lens blog wrote about Woods and State here .

3 comments on “ Identity Politics: an interview with Paolo Woods ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Great interview and incredible images. Very interesting to read Paolo’s thoughts on NGOs and the aristocracy of Haiti.

Thanks, Robin. I wish I could have put more of the images up, because they’re really amazing. Worth checking out on Paolo’s site or the NYT Lens blog (links above).

Will do! Thanks.