From Eye Candy to Icon: Influential Movie Moments

A former astronaut, whose rocket ship seems to have time-traveled to the distant past, is riding on horseback along a beach. After years of being imprisoned by a master race of talking apes, he has escaped with a mute human slave girl for company. They ride down the beach, and we see them from between two triangular spikes in the foreground. Then the man dismounts, sinks to his knees and starts pounding his fists in the surf. “You maniacs, goddamn you, you blew it up!” he shouts. The camera recedes and we see what he’s looking at: the blackened, half-buried Statue of Liberty.

When I was seven or eight, that final scene of the 1968 film

Planet of the Apes

terrified the crap out of me. I lived in London, but understood the symbolism of the Statue of Liberty and knew what it meant in that scene. Astronaut George Taylor had traveled not into the past, as he’d assumed, but to a brutal, post-apocalyptic future. His hopes for mankind were shattered.

When I was seven or eight, that final scene of the 1968 film

Planet of the Apes

terrified the crap out of me. I lived in London, but understood the symbolism of the Statue of Liberty and knew what it meant in that scene. Astronaut George Taylor had traveled not into the past, as he’d assumed, but to a brutal, post-apocalyptic future. His hopes for mankind were shattered.

To this day, Lady Liberty gives me the creeps.

In his new book, Moments that Made the Movies , British movie critic David Thomson looks at 125 years of film through almost seventy iconic scenes. It’s a fresh, interesting approach: movies are narrative by nature, but they’re also made up of scenes and still images that imprint themselves on our brains. Filmmakers labor hard to produce such moments, only to have many critics gloss over them in reviews.

“Do you remember the movies you saw, like whole vessels serene on the seas of time?” Thomson asks in the book’s introduction. “Or do you just retain moments from them?” Both, perhaps—but I’m susceptible to Thomson’s argument that “often the moment has overwhelmed the film itself.”

“Do you remember the movies you saw, like whole vessels serene on the seas of time?” Thomson asks in the book’s introduction. “Or do you just retain moments from them?” Both, perhaps—but I’m susceptible to Thomson’s argument that “often the moment has overwhelmed the film itself.”

That could definitely be said for some films included here, like Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 Blow Up , in which a young photographer named Thomas takes a sequence of photographs that he comes to suspect might reveal a murder in a park. I remember the film being opaque and frustrating (the mystery never gets resolved), but Thomson makes a case for it being historically significant. “People looked very closely at photographs and grassy knolls in the 60s,” he points out, referring to a scene where Thomas prints his photos and blows up details, “and surely they saw things in them. I think in the history of photography it was a critical moment. Today, we are far more bored with pictures.”

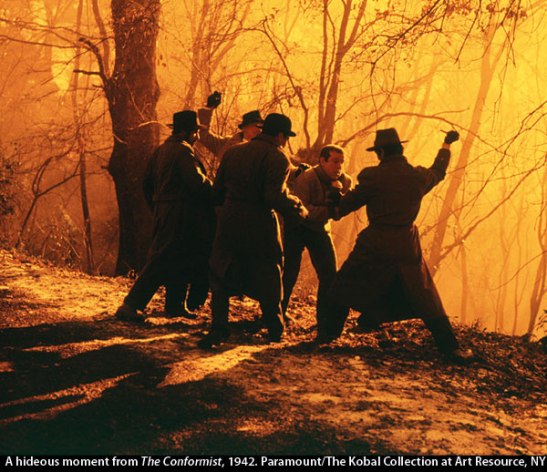

A similar thing could be said about David Lynch’s Blue Velvet , whose perverse creepiness was shocking in 1986, but seems almost tame now. I remember the movie for the way it picked up a corner of the American Dream and exposed the rot underneath. (“Yes, that’s a human ear,” a detective intones flatly when the horrified teenager played by Kyle McLachlan brings him a piece of flesh.) Thomson picks a different scene: the lurid one where Jeffrey is introduced to the amoral world of Frank (Dennis Hopper) and his buddies. The movie is “a fairy story about a boy and a girl, a witch and a beast,” he writes. Seldom had such dark style been applied to the archetype.

Iconic moments need not be climactic. Often, Thomson steers around a movie’s big, set pieces in favor of smaller, revealing moments. The climactic shoot-out in

Bonnie and Clyde

is far less interesting to him than an earlier scene where Warren Beatty’s Clyde seduces Faye Dunaway’s Bonnie into a life of crime over a burger in a diner. In

Psycho

, he picks the quiet scene directly before the infamous shower scene, when the murderer-to-be presents himself as “the first gentle, sympathetic or insightful person in the film.”

Iconic moments need not be climactic. Often, Thomson steers around a movie’s big, set pieces in favor of smaller, revealing moments. The climactic shoot-out in

Bonnie and Clyde

is far less interesting to him than an earlier scene where Warren Beatty’s Clyde seduces Faye Dunaway’s Bonnie into a life of crime over a burger in a diner. In

Psycho

, he picks the quiet scene directly before the infamous shower scene, when the murderer-to-be presents himself as “the first gentle, sympathetic or insightful person in the film.”

He also recounts some off-celluloid moments that are hugely revealing—like the 1940 Oscar ceremony, when Hattie McDaniel received the Academy Award for her portrayal of Mammy in Gone with the Wind . “You might have imagined that [director David O.] Selznick would have had her at the large central table for the Wind people. Not so. At the Academy Award ceremony, Hattie McDaniel and her companion were at a small table for two, off in a corner of the big room,” Thomson writes, adding with acidity, “Moments.” (To be fair to Selznick, he had earlier protested when McDaniel wasn’t invited to the film’s premiere in Atlanta.)

Thomson’s picks are eclectic and personal. Along with expected targets ( Gone with the Wind , Citizen Kane , Casablanca , North by Northwest ) he includes other, more esoteric fare ( Sansho the Bailiff , anyone?) He particularly likes European directors Michelangelo Antonioni and Alain Resnais, and comedy gets pretty short shrift here.

But if there are omissions, there are also unexpected delights—from offbeat picks like Jane Campion’s failed 2003 In the Cut to Thomson’s own chatty admissions of failure (“I thought I had this one tidied up.”) And I especially loved that this personal selection is bookended with two still images that, in Thomson’s mind, are as influential as any movie scene.

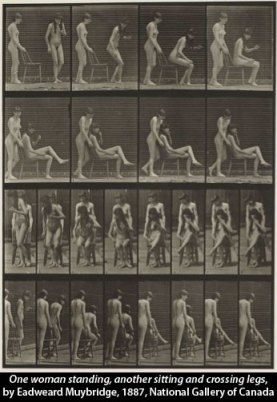

The first, from 1887, is a 24-frame motion study of two naked women by

Eadweard Muybridge

, whose famous studies, first undertaken to prove that a horse’s four legs all leave the ground during a gallop, were a precursor to film. The information the studies revealed was exhilarating. “It’s 1887 and it’s obvious: We are having such fun as time passes,” Thomson writes. “That’s what we hardly knew before—it wasn’t just the horse, we were flying too.”

The first, from 1887, is a 24-frame motion study of two naked women by

Eadweard Muybridge

, whose famous studies, first undertaken to prove that a horse’s four legs all leave the ground during a gallop, were a precursor to film. The information the studies revealed was exhilarating. “It’s 1887 and it’s obvious: We are having such fun as time passes,” Thomson writes. “That’s what we hardly knew before—it wasn’t just the horse, we were flying too.”

The still image that closes the book is less clear. A news photo from 2011, taken by Rich Lam of Getty Images, it was shot when crowds rioted in Vancouver after the local team was beaten in the Stanley Cup. The photograph, of a young couple lying prone in the road, kissing as riot police swarm around, is mysterious and alluring. Thomson uses it as an example of photography’s ambiguity and our need to impose narrative on it. “As soon as you look at a picture, you have crossed the threshold of fiction,” he writes.

All this jumping around feels heady and stimulating. It’s a bit like getting a plate of different

amuse-bouche

s from a creative chef: while some may be so-so, others will make you hungry for more. (“I hope the moments will send you in search of the whole films,” Thomson writes.) At best, they’re insightful and provocative, and will lead you to reconsider some classics, discover new works, and think of film moments that have tunneled themselves into your own brain.

All this jumping around feels heady and stimulating. It’s a bit like getting a plate of different

amuse-bouche

s from a creative chef: while some may be so-so, others will make you hungry for more. (“I hope the moments will send you in search of the whole films,” Thomson writes.) At best, they’re insightful and provocative, and will lead you to reconsider some classics, discover new works, and think of film moments that have tunneled themselves into your own brain.

“Movies often feel claustrophobically organized,” Thomson writes at one point, praising a scene in Infamous where a character’s momentary breakdown is more realistic for being left unexplained. For sure this book is not claustrophobically organized, and that’s part of its charm.

What is a movie moment that made a deep impression on you? Please share below!

5 comments on “ From Eye Candy to Icon: Influential Movie Moments ”

Information

This entry was posted on October 29, 2013 by sarahjcoleman in Books , Films and tagged Alfred Hitchcock , Blow Up , Bonnie and Clyde , Casablanca , Charlton Heston , David Lynch , David O. Selznick , David Thomson , Eadweard Muybridge , Gone with the Wind , iconic movie moments , In the Cut , Jane Campion , Michelangelo Antonioni , Movie History , North by Northwest , Planet of the Apes , Psycho , Statue of Liberty , The Conformist .Shortlink

https://wp.me/p25Qfq-yTRecent Posts

Archives

Categories

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Join 11,055 other followers

So many movies, so little time! If it is just one I will have to chose from Network (1976) the scene when Ned Beatty gives the lecture to Peter Finch. I also value immensly the seperation speech of William Holden towards Faye Dunaway.And just for the cinematic surprise of it the scene where Peter Finch suggests to the viewers to go at their windows and shout: I’m mad as hell and I am not going to take it anymore.

In fact all the movie is packed with memorable scenes.

I could also add Brazil, or The three colours of Kislowski, or even films like Blues brothers or the life of Brian. Why such funny films always go under the radar is beyond me. They are seriously funny and deal with many aspects of life in a much more approachable fashion.

And Blow up really has an end, silent yet sharp clear, at the final rennis court scene. That the truth is not out there, in the dots of a super magnified print, but it is deep inside each and everyone of us, we just have to learn to see it.

Great picks, Vassilis! Thanks for taking the assignment seriously 🙂

Hey, how about yours? 😉

Here are a few that come to mind:

WITNESS: the barn-building scene. A vision of simplicity and collaboration that contrasts starkly with the brutality we’ve seen earlier in the movie.

WALKABOUT: It’s a while since I’ve seen it, but the relationship between the Aboriginal youth and the two stranded white kids is really amazing. And there’s a shocking scene where the father combusts himself and his car.

THE DIVING BELL AND THE BUTTERFLY: No scene in particular comes to mind, just the overall impression of the film, which was a profound look at what it means to be human.

AMOUR: Similarly, this is a film that is more about the whole than the sum of its parts — but I particularly remember the quiet scene where the wife is looking at an old photo album in the kitchen, and the dramatic scene where she spits at her husband.

THE CONSTANT GARDENER: The sex scene in this movie stands out for me because it is more about friendship than about passion. There is giggling, which you don’t often see in movie sex.

I’m sure there are others too…

I have only seen the first and last of your choices and they are wonderful movies. I like the quite and intimate moments you choose. Will search for the rest and let you know!