Little Bigshots: An Interview with Shree K. Nayar

Cameras can be pretty daunting these days. With features like HD video, hybrid autofocus and geo-tagging, photography has moved a long way from the days when a consumer camera

was made out of cardboard and cost $1

.

Cameras can be pretty daunting these days. With features like HD video, hybrid autofocus and geo-tagging, photography has moved a long way from the days when a consumer camera

was made out of cardboard and cost $1

.

The fact is, though, you don’t need a ton of bells and whistles to make a camera exciting. Digital developments aside, the basic concept of capturing light and making an image has captivated people for almost two hundred years, and its core principles remain the same. How cool would it be, then, to teach kids to make their own digital cameras?

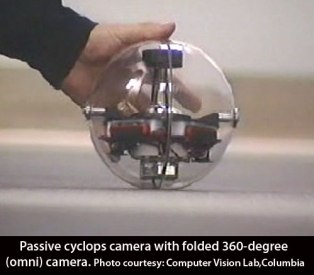

That’s the thought that occurred to Shree K. Nayar some years ago. A professor of computer science at Columbia University, Nayar works in the field of computational imaging—which usually means making futuristic things like a robot-controlled 360-degree camera . Eight years ago, though, Nayar began toying around with a concept for a kit that would teach kids scientific principles through the construction of a digital camera.

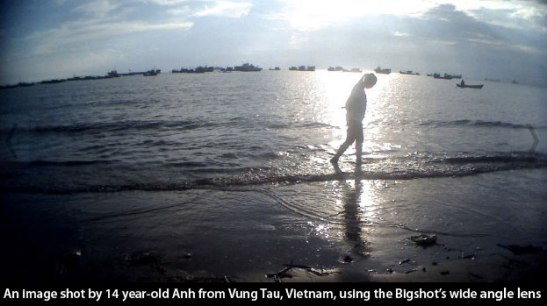

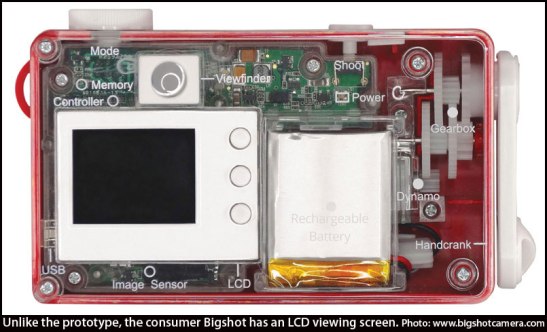

Part of Nayar’s vision was to help educate children globally, and during the camera’s evolution Nayar and his graduate students took a set of 15 prototypes to India and Vietnam, getting feedback from children there as well as from their more privileged peers in the U.S. In order to cram in as much science as possible, they included features that weren’t strictly essential, like a power generator with dynamo and gears, and a polyoptic wheel with lenses including a stereo one for producing 3D images.

Part of Nayar’s vision was to help educate children globally, and during the camera’s evolution Nayar and his graduate students took a set of 15 prototypes to India and Vietnam, getting feedback from children there as well as from their more privileged peers in the U.S. In order to cram in as much science as possible, they included features that weren’t strictly essential, like a power generator with dynamo and gears, and a polyoptic wheel with lenses including a stereo one for producing 3D images.

The camera, pleasingly called Bigshot (in the hope, says Nayar, that it can turn any child into an artist or engineering big shot) is now on the market, with a wonderful website that explains the scientific principles behind every component . (The site also has some nifty quizzes on photo art and history.) Nayar, who remains deeply devoted to the project, plans to donate part of his royalties to under-served communities around the world.

Last week, Nayar (who—full disclosure—is a friend and neighbor) generously made time for The Literate Lens while preparing for a business trip to Japan. We spoke in his office on the Columbia campus, surrounded by experimental cameras that looked a bit like floating drones from a Star Wars movie.

Literate Lens: How does it feel to have the Bigshot camera out in the world after years of research and development?

Shree Nayar: It’s really exciting, but it’s also a pretty insane thing for an academic to do, to have a product that people buy and put together, and you have to make sure they’re satisfied with the experience. As an academic I usually write papers, and there aren’t many risks because the world at large doesn’t take any notice! If it weren’t for this project having a social and educational component, I wouldn’t have done it. I’m not interested in building cameras to make money out of cameras. But in this case, I loved the project so much that I was prepared to stick my neck out.

LL: How did you first get interested in photography?

SN: Well, I have a confession to make: I’m not an avid photographer or an early adopter of new photo technology. The camera I own is always five years behind the times. But I’ve always been aesthetically inclined: if I hadn’t been an engineer I could have become an architect or designer. What I love about computer vision is that there’s a very visual and aesthetic aspect to it. I find that very attractive, even though I’m not someone who frames and shoots on a regular basis.

LL: I watched your TEDx talk where you spoke about the influence of your father, who was a great builder and fixer. Did he inspire you to become an engineer?

SN: Without a doubt. I’d spend hours watching him put things together. None of our possessions were ever sent away to be fixed. When I was 7 or 8, he bought the shell of a Bug Fiat car, and, with the help of two mechanics, bought parts from all over and built the car up from scratch. I watched them do it. When my sister and I went out for our first ride, we stood up on the back seat with our heads sticking out of the car’s sunroof, which was exhilarating. Much later, I realized my father had done something huge—he’d built a car! It made me realize that a lot of things I might think were daunting weren’t, that you can take a complex thing and break it down into its parts.

LL: And there’s such excitement and pleasure in doing that. When I watched the TEDx talk , it occurred to me that the Bigshot was a modern extension of the thrill some of us used to get in developing and printing our own film. You’re doing something tactile…

SN: Yes, and it’s not just that. It’s remarkable to me how our kids’ generation is so comfortable with software and almost instinctively learns how to use it. But software will always have to sit on top of something, it’s nothing by itself. There’s going to be a next generation of that stuff it sits on, and we need to be training the next generation of builders of that stuff.

LL: So when and how did the idea begin?

LL: So when and how did the idea begin?

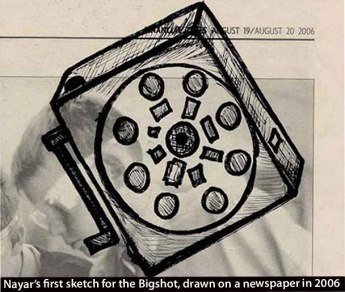

SN: In the mid 1990s, my lab was designing cameras for high-end applications. But then I thought, why not do something with broader social impact? I started making sketches, thinking about what might inspire kids’ creativity and educate them in the process. I used some discretionary funds from Columbia, got a grant from Google, and contacted people who were good at design and optics. This was a side project, but it quickly became very compelling. I dabbled for a year, then I saw Born into Brothels , Zana Briski’s 2004 documentary about giving cameras to children in a Calcutta brothel, which really inspired me. I saw how the camera could be used to lure people who wouldn’t typically be drawn to the sciences. I thought, there’s a good chance I won’t succeed at this because design and manufacturing are new to me, but it’s worth a shot.

LL: At first you made 15 prototypes and did field testing in New York, Bangalore and Vietnam. What did you learn from those tests?

SN: We had equal numbers of boys and girls, and lots of diversity in terms of socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds, but across the board the kids were enthusiastic. That was interesting to me because with most consumer kits like robots or electronics, it’s already engineering or science and you often have to be initiated into that space to get engaged. But cameras are so universal that here, you can use the arts to veer the kids toward science, and vice versa.

LL: Was there any difference in how the different groups of kids approached the project?

SN: Absolutely! We had one workshop here in New York with children from a private school, and those kids wanted to know why it’s not a 15-megapixel camera, why there was no metering. They were way out there! Then there were kids in India who’d never taken a photograph before. For each group, we had a questionnaire to fill out—we asked what was easy or difficult to build, what was most fun to learn, et cetera—and we tried to incorporate their feedback. For example, the prototype didn’t have an LCD display because we wanted to reduce costs and also add a surprise element. But the kids all said no, it would be good to have an LCD display, so we added that to the final product.

LL: How did you go about finding a company to manufacture the kit?

SN: It was hard. At first I was looking at the big name camera companies, because I wanted a high quality product and obviously they know how to make cameras. I work with many of these companies in my research, and I knocked on a lot of doors, but they all said that although they build cameras and put them on the shelves, education was something they didn’t understand. Then, after a year of searching, EduScience got in touch with me out of the blue and said they’d like to produce the camera. I went to China to see their factory: it’s relatively small, and I saw they could do what we needed. It was pretty much my only option so I decided to go with it.

LL: How’s the quality?

SN: It’s a pretty low-end device. The sensor is 3 megapixels, which is fine for any online application. In the future, though, if it goes into a second generation, I’d hope to get a sensor of 5 to 8 megapixels, slightly better optics, video and WiFi for around the same cost. Those decisions were ultimately made by EduScience: it’s their product. The company I founded, Kimera, doesn’t make or sell cameras. We get royalties, part of which will go toward providing cameras to kids in under-served communities.

LL: Originally you envisioned a global social networking component to this project, so that kids could connect with their peers in other countries. What happened to that?

SN: When it was just a project at Columbia, we deployed a system called BigShot Connect with a small group of students. It was like a Flickr for kids: you could upload pictures to a gallery, and kids could like or tag them. It was very ambitious, a substantial software project. But all the time, I was worried: you have to ask, if kids are giving their names, ages and a self portrait, what kinds of implications are there? I got in touch with some friends at Yahoo, which owns Flickr, and they basically said, this is something you should stay out of. They have thousands of employees dealing with these issues, and we had one and a half people! So we developed it and just dropped it. It was a beautiful gallery, but from a practical standpoint it couldn’t work.

LL: That’s too bad. But looking forward—since you work in computational imaging, I have to end with this question. What do you think is the next frontier for consumer photography?

LL: That’s too bad. But looking forward—since you work in computational imaging, I have to end with this question. What do you think is the next frontier for consumer photography?

SN: So far, the innovations in digital camera technology have been based on the conventional photography architecture and paradigm—basically, the lens and sensor. My field, computational imaging, looks at it a bit differently. Our view is that the image captured on the sensor doesn’t have to be the final image you consume. For example, you could do post-capture control on the image: say, if you wanted to change the area of focus. This is called computational decoding, and it’s very different from using Photoshop. In computational decoding, you’re combining the lens optics with a program to do something that was previously very expensive and heavy and big. A lot of things like that are beginning to surface now—a company called Lytro is actually using computational decoding to change focus. I’m not saying the camera as it stands will be completely displaced or replaced. But there will be some really interesting variants coming along.

——————————————-

Visit the Bigshot camera site here .

Visit Shree K. Nayar’s research page here .

Watch Shree K. Nayar’s TEDx talk about the Bigshot camera.

One comment on “ Little Bigshots: An Interview with Shree K. Nayar ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Thank you for bringing it to my attention! A very nice project. I like the building part very much, although I wish it was up from essentials, rather than building a kit. (yes, I know I ask too much). Also the problem that is raised on the last but one answer, (about personal data from minors) is rather a sociological issue, that shows that technology changes the world faster that the people are ready to take in the changes (don’t say evolve, because I feel that it is more like mutate).