Three Worthy Gift Books

It’s that time of year again: the time when stores are full of tinsel, acapella versions of The Little Drummer Boy go viral, and year-end best-of booklists start popping up all over the place. I briefly considered doing a Literate Lens best-of-2013 booklist, but changed my mind because there are so many lists out already. Instead, I’d like to take this opportunity to write about three worthy books that, for one reason or another, I didn’t manage to blog about earlier in the year.

CAPTURING THE LIGHT: The Birth of Photography, a True Story of Genius and Rivalry

, by Roger Watson and Helen Rappaport (St. Martin’s Press, $20.86)

CAPTURING THE LIGHT: The Birth of Photography, a True Story of Genius and Rivalry

, by Roger Watson and Helen Rappaport (St. Martin’s Press, $20.86)

Henry Fox Talbot and Louis Daguerre couldn’t have been more different. A restrained, well-educated Victorian Brit, Fox Talbot was “by nature reclusive and bookish” whereas the flamboyant French Daguerre was “light-hearted and a natural exhibitionist,” barely schooled and known for entering parties walking on his hands. Yet each man seized on the same challenge: to stop time by capturing a photographic image. And after a series of false starts, both succeeded.

A double biography, Capturing the Light tells the highly entertaining story of how each of these men came to make history. Like photography itself, the book is a study in contrasts: while gentleman-scientist Fox Talbot is methodical and coherent to a fault, Daguerre scrambles along in an effort to beat the competition and save himself from financial ruin. Though unaware of each other’s inventions at the time of development, the two were working at the same time, and authors Watson and Rappaport build tension in alternating chapters, making us wonder which man will break through first.

As part of this origin story, Capturing the Light also gives due to some lesser-known but important figures. You may have heard, for example, of Joseph Nicéphore Niépce , whose View from the Window at Le Gras is considered the first true photograph—but how much do you know about him? In Capturing the Light , we learn of Niépce’s rather sad history—which doesn’t reflect well on Daguerre. Desperate not to be pipped at the post by the older, more scientifically rigorous man, Daguerre charmed Niépce into a rather one-sided collaboration, then reaped the rewards after Niépce died in poverty in 1833.

All of this unfolds at a time when technology was progressing almost faster than people’s ability to harness it, and scientific inquiry was peaking. (If that sounds like our own time, consider also that who you knew was almost as important as what you knew—Daguerre profited hugely from connections.) Though Watson and Rappaport’s style can veer toward the academic at times, they do a great job of evoking that era’s sense of possibility, so that we feel Daguerre’s excitement when, after years of experimentation, he announces with typical grandiosity, “I have seized the light. I have arrested its flight.”

UNTOLD: The Stories Behind the Photographs

, by Steve McCurry (Phaidon Press, $59.95/$40.65 on Amazon.com)

UNTOLD: The Stories Behind the Photographs

, by Steve McCurry (Phaidon Press, $59.95/$40.65 on Amazon.com)

The photograph in the frontispiece of Steve McCurry’s new book—of McCurry submerged armpit-deep in water on a monsoon-ridden Indian street, holding his camera and bag above his head as he scouts for images—tells you everything you need to know about the photographer’s character: his determination is written on his face. Untold , on the other hand, shows some of the less obvious behind-the-scenes work that was necessary for McCurry to take some of his signature shots, including Afghan Girl , consistently rated one of the world’s most famous and/or most recognizable photographs.

Though he’s known for sensitive, colorful portraits like Afghan Girl , Untold reminds us that McCurry built his career on a foundation of hard-hitting photojournalism. We learn about his breakout work in Afghanistan in 1979, when he was smuggled into the country by mujahideen, and about the horror he experienced in Kuwait in 1991, when he documented the aftermath of the first Gulf War. There’s a devastating section on September 11th, when McCurry was one of the first photojournalists on the scene at Ground Zero, and some heartbreaking images of India’s poor.

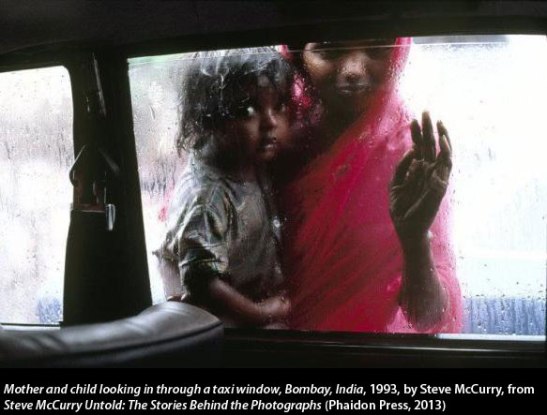

In one of the book’s most telling anecdotes, McCurry recounts the feelings he had while making the above image of a mother and child begging in India. His car was stopped in traffic in Bombay, and a woman approached the window. “I raised my camera, took two frames, the light changed, and off we went—it all happened in about seven of eight seconds. Two months later, I came across these two frames when I was editing the pictures in New York. I was delighted that the picture came out as well as it did. It seemed to symbolize the separation between my world and hers—I’m in this air-conditioned bubble, she’s out there in the heat and the rain.”

The book’s generous size makes images such as this one especially powerful. Also included are excerpts from McCurry’s notebook pages, train tickets and maps, and although there’s a whiff of the kitchen sink in this assemblage of ephemera (McCurry seems never to have thrown a single receipt away), it underscores the research and effort necessary for this kind of work. Readers might feel a similar sense of privilege and separation as McCurry did in that Indian taxi—but the photographer’s genius is that he helps us bridge the divide.

MARY COIN

, by Marisa Silver (Blue Rider Press, $21.01 on Amazon.com; paperback due out in February 2014)

MARY COIN

, by Marisa Silver (Blue Rider Press, $21.01 on Amazon.com; paperback due out in February 2014)

There’s recently been an increase in the number of novels based on the lives of famous photographers, which is a source of both delight and anxiety for me as I’ve been working on my own historical photographer novel for the last five years. (Rest assured, you’ll hear plenty about it if/when it’s published.) Typically I rush to pick up any and all novels of this type, and generally I blog about them (see here and here ). When Marisa Silver’s Mary Coin came out earlier this year, though, I couldn’t get myself to pick it up. At the time, I was working on a major revision of my novel, and Silver’s period setting and thematic preoccupations seemed too similar to my own. Since the book was very well reviewed, I was worried it would somehow make mine redundant and sap my will to finish.

I’ve finally bitten the bullet and read the novel, and I’m very glad I did. Based on Migrant Mother , the iconic Dorothea Lange photograph that came to symbolize the sufferings of the Great Depression, Mary Coin is a sensitive portrayal of two notable women.

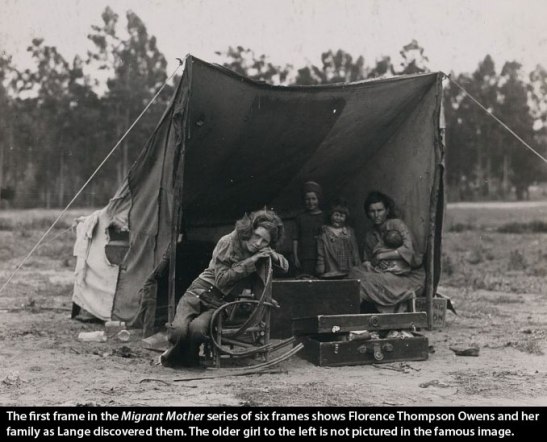

The story around Migrant Mother has been retold many times , becoming part of the mythology around the image. Basically, it goes like this: In 1935, Lange was documenting the Depression for the Farm Security Administration’s photography program when, driving home from an assignment in California’s Central Valley, she drove past a battered sign pointing to a pea-picking camp. Initially eager to get home, she drove past, but twenty miles down the road she changed her mind and drove back. Outside the camp, by a broken-down truck, she found a makeshift tent harboring Owens and four dirty children. Drawn by the woman’s striking appearance, Lange asked permission and shot six frames, each time coming a little closer, but, according to FSA rules, never asking the woman’s name. In the final frame, something magical happened: two of the children turned their backs to the camera while a third nestled at Owens’ breast. Looking off to the side with a worried but stoic expression, Owens was a modern Mother Courage .

The novel unfolds through three points of view. Lange becomes Vera Dare, a brilliant young photographer who’s looking to document something more enduring than the vapid society women her San Francisco studio attracts. Owens is Mary Coin, an intelligent half-Cherokee woman who’s almost impossibly burdened by harsh circumstances. A third, invented character, Walker Dodge, is a history professor with a possibly personal stake in finding out about Mary’s life.

Hewing closely to the known facts of the two women’s biographies, Silver uses gorgeous language and astute observations to endow them with emotional lives that feel just right. Her two main characters are both tough women living through hard times, but Silver doesn’t sentimentalize them—they both have obvious flaws as well as strengths. She also writes uncommonly well about the emotional pull of photography and its effect on everyone involved—shooter, subject, viewer. Consider, for example, this passage where Mary first sees Vera Dare’s photograph of her in a newspaper:

She’d felt angry at the woman in the picture for being so thin, and ashamed that her children were dirty, and, oh, all right, a little bit excited because now her kids were jumping up and down, yelling about how their mama was in the newspaper, and other women from the camp to see what all the noise was about. But later, when she was alone, she felt something else that made fear and shame and pride a lie: she felt jealous. She was envious of the woman in the picture because that woman had not had to suffer the future that began the moment the photographer got into her car and drove away.

I’ve written before about the issue of changing names in novels based on real people. Often I’m not in favor, but I didn’t mind it here, because Mary Coin is a triumph. Silver’s choice to rename the two women tips us off that this book is an imaginative invention, but her characters are so full and real that before long, I simply didn’t care what their names were.

Taking on such a beloved and well-known image is a bold move, and a lesser novelist might have screwed it up. But Silver’s writing is everything you could want it to be: its clarity and power do justice to this amazing image.

Finally, I have a modest request. Come January 2014, I’ll have been putting out The Literate Lens for two years. Up to now, I’ve published 44 feature-length articles, gotten over 134,000 page views and attracted 1,150 subscribers and fans. My top post, Magnum and the Dying Art of Darkroom Printing has been seen over 72,000 times on The Literate Lens and has been republished and translated into at least six languages, and many of my posts have been syndicated to The St. Petersburg Photographer . All of this is a labor of love.

Recently I joined the Amazon Associates program, which means that if you click through to Amazon.com from this site and buy anything within 24 hours, I get a small commission. I’d rather do this than include advertisements or charge subscription. Please consider supporting The Literate Lens this holiday season by using one of the book title links above (or the Amazon links in this paragraph) to get to Amazon.com when you shop. And have a wonderful, literate holiday season!

Information

This entry was posted on December 9, 2013 by sarahjcoleman in Books , Novels and tagged Afghan Girl , calotype , Capturing the Light , daguerrotype , Dorothea Lange , Florence Thompson Owens , Helen Rappaport , Louis Daguerre , Marisa Silver , Mary Coin , Nicéphore Niépce , Roger Watson , Steve McCurry , Untold: The Stories Behind the Photographs , Vera Dare , View fron the Window at Le Gras , William Henry Fox Talbot .Shortlink

https://wp.me/p25Qfq-EBRecent Posts

Archives

Categories

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Join 11,055 other followers

All of these reviews make each book sound so interesting….must reads….thank you.

You’re welcome, Sally! Happy reading!

Very interesting suggestions, although I will probably wait a bit to obtain any of them when I have the time and finances.

Niepce’s story is very strong, although Daguerre did look after Niepse’s son, when he “traded” “his” invention for life long pensions for him and Niepse’s son. . And there is a lot of talk about the FSA photography program and the famous Lange photos.

All the books you have recommended are gems. I got Steve McCurry’s Untold I got as a gift and Capturing the light I bought it recently. MARY COIN I jut bought as kindle edition. Yes, I did bought it through your amazon link 🙂

The for the recommendations.

I will also look forward to your novel. I am not sure it has come out already .. Just discovered your blog and going through it !!

Thank you so much, Ajith! I’m glad you’re enjoying the book recommendations. My novel has not come out yet. I’m working on what will (I hope) be the last revision. You can be sure that readers of The Literate Lens will hear plenty about it when it is published!