Art Therapy

“So, Sarah, how can I help?” Thus begins my interview with

Saul Robbins

, distinguishing it from countless photographer interviews I’ve conducted over the years. For unlike other photographers, Robbins isn’t asking how he can best provide me with information about himself. He’s inquiring how he can weigh in on

my

personal problems.

“So, Sarah, how can I help?” Thus begins my interview with

Saul Robbins

, distinguishing it from countless photographer interviews I’ve conducted over the years. For unlike other photographers, Robbins isn’t asking how he can best provide me with information about himself. He’s inquiring how he can weigh in on

my

personal problems.

Clearly, Robbins is not your average photographer. His most recent project, How Can I Help? – An Artful Dialogue , is unique, taking the concept of the “concerned photographer” to a whole new level. Rather than simply consuming images on a wall, viewers are asked to consider their own vulnerabilities. Sitting among Robbins’ photographs of therapists’ offices, willing participants enter into what Robbins calls an “earnest, heartfelt dialogue” about their problems, with the aim of creating a connection and fostering a sense of community.

“We live in a local environment in which people are pretty disinterested in talking to strangers,” Robbins says. “You get on the subway and it’s crowded and chaotic, but people don’t make eye contact. There’s no sense of how we’re in this together.”

Perhaps that’s why so many New Yorkers flock to therapists’ offices, though results can be decidedly mixed. In fact, How Can I Help? grew out of Robbins’ frustration with his own therapist, whose “bland, mediocre” office environment seemed to reflect the man’s personality. One day, Robbins walked into the office and saw a vase of dead flowers. “To me, that signaled his lack of interest,” he says. Searching for a way to address his frustration, he asked if he could photograph the therapist’s empty chair.

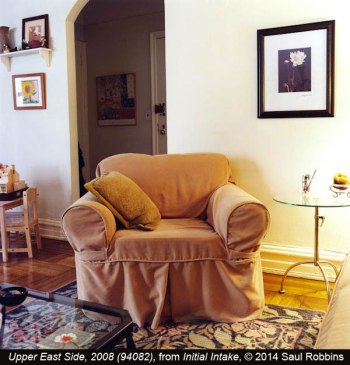

What grew from that was

Initial Intake

, a series of portraits of therapists’ offices. Shot from the perspective of the patient, each image features a therapist’s chair and its surroundings, and looking through the series is enlightening. Though there’s an iconography common to many of the offices (padded chair, Oriental rug, soothing artwork on the walls), the rooms also express individuality. In one, a lamp shaped like a Buddha sits serenely on a desk. In another, a generic ‘OPEN’ sign dangles from a closet doorknob while a dog watches balefully from a nearby cushion.

What grew from that was

Initial Intake

, a series of portraits of therapists’ offices. Shot from the perspective of the patient, each image features a therapist’s chair and its surroundings, and looking through the series is enlightening. Though there’s an iconography common to many of the offices (padded chair, Oriental rug, soothing artwork on the walls), the rooms also express individuality. In one, a lamp shaped like a Buddha sits serenely on a desk. In another, a generic ‘OPEN’ sign dangles from a closet doorknob while a dog watches balefully from a nearby cushion.

The focus on detail came naturally to Robbins, whose previous work had been concerned with isolating objects and gestures. In his series This Life So Far , he documented small, everyday gestures of family members and friends in order to explore “the depth of expression contained in the simplest of situations.” In Found , he reinterpreted a Jewish edict to reunite owners with lost property, painstakingly photographing lost gloves, then retrieving them and taking them home to be washed, leaving behind a note with his phone number and email address.

But it wasn’t until Initial Intake that Robbins started considering a more active engagement with viewers. Realizing he liked interacting with people, he envisaged some sort of dialogue around the work. When he heard about the organization chashama , which provides non-traditional spaces for artists to do new work, the idea for How Can I Help? was born. “The possibility of using my art in multiple ways, going beyond the purely visual, was interesting,” he says.

In a way, it was a no-brainer: therapy runs in Robbins’ family. His parents and sister are all psychotherapists, and he’d long been interested in their line of work. But perhaps more than that, he said, his experience as a photography teacher at the International Center for Photography equipped him for his new role. “As a teacher, I often discuss students’ personal work and identities,” he says. “The discussions in

How Can I Help?

are similar. I’m not a qualified psychologist, but I do have an ability to talk to people. It’s not an ego-stroking process: I’m not trying to be anyone’s brother or father figure. I’m just a mirror.”

In a way, it was a no-brainer: therapy runs in Robbins’ family. His parents and sister are all psychotherapists, and he’d long been interested in their line of work. But perhaps more than that, he said, his experience as a photography teacher at the International Center for Photography equipped him for his new role. “As a teacher, I often discuss students’ personal work and identities,” he says. “The discussions in

How Can I Help?

are similar. I’m not a qualified psychologist, but I do have an ability to talk to people. It’s not an ego-stroking process: I’m not trying to be anyone’s brother or father figure. I’m just a mirror.”

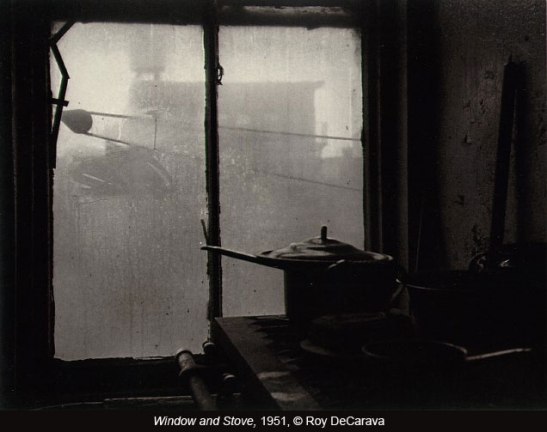

In that regard, Robbins learned from the best. His own teacher was the great Harlem photographer Roy DeCarava , known for his lyrical images of African Americans. “I was his teaching assistant, and he was my mentor,” Robbins says. “Watching him with students, I was always amazed at how attuned he was. He zeroed in on details I’d never have thought of.”

At chashama, Robbins aspired to the same kind of sensitivity. To avoid confusion, he explains in advance that he is not a trained or licensed therapist, and tries not to dispense advice. But he does believe artists bring creativity to the art of listening. “I’m extremely visually attentive, and detail-oriented,” he says. “I’m always trying to make eye contact and pay attention to those subtle clues.”

At chashama, Robbins aspired to the same kind of sensitivity. To avoid confusion, he explains in advance that he is not a trained or licensed therapist, and tries not to dispense advice. But he does believe artists bring creativity to the art of listening. “I’m extremely visually attentive, and detail-oriented,” he says. “I’m always trying to make eye contact and pay attention to those subtle clues.”

Most recently, Robbins took

How Can I Help?

to

Photoville 2014

, the annual pop-up photography festival that takes place in shipping containers on the Brooklyn waterfront. Realizing he’d need help to deal with eight days’ worth of visitors, he recruited four others to sit in the listening chair, but handled sixty percent of the traffic himself. The conversations, he says, were intense. “A lot were about creativity or the life-work balance, but there were two back-to-back meetings about elderly parents, one of which concerned dementia,” he says. Even conversations with people who started by saying, “I don’t know what I want to talk about” ended up being profound.

Most recently, Robbins took

How Can I Help?

to

Photoville 2014

, the annual pop-up photography festival that takes place in shipping containers on the Brooklyn waterfront. Realizing he’d need help to deal with eight days’ worth of visitors, he recruited four others to sit in the listening chair, but handled sixty percent of the traffic himself. The conversations, he says, were intense. “A lot were about creativity or the life-work balance, but there were two back-to-back meetings about elderly parents, one of which concerned dementia,” he says. Even conversations with people who started by saying, “I don’t know what I want to talk about” ended up being profound.

In future, Robbins envisages expanding the project even further. He is currently discussing the possibility of taking it to a neighborhood known for gun violence, using the format to involve people in a dialogue about gun control. “For me, this addresses some of my social and political beliefs,” he says. “The idea of a more provocative, activist project is fascinating.”

And so, back to my fifteen-minute “initial intake” conversation with Robbins. How

did

he help? Well, without getting into the specifics of what we discussed, I can say he was an excellent, sympathetic listener. His reactions affirmed that my feelings were justified and appropriate, and I came out feeling supported and heard.

And so, back to my fifteen-minute “initial intake” conversation with Robbins. How

did

he help? Well, without getting into the specifics of what we discussed, I can say he was an excellent, sympathetic listener. His reactions affirmed that my feelings were justified and appropriate, and I came out feeling supported and heard.

What’s it like to be this kind of receptor? A cynic might wonder if Robbins is a man in search of a god complex, but he seems entirely free of vanity, and impressively humble. “I try to approach this with humility,” he says. “Touching on people’s lives in this way is an honor. I’m not invested in being an expert; I just want to create a safe space for people to talk and think about healing.”

And that, god knows, is something we could all use in our lives.

3 comments on “ Art Therapy ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

I really liked this piece…and I’m not sure why exactly, it just resonated with me. I think there’s something ambiguous about the intimacy that’s created when two people just sit and talk in the knowledge that they’ll never meet again.

Great to read these blogs Sarah!

Reading your article gave me a warm and fuzzy feeling. Saul is a photographer and philanthropist? Or is he a sensitive and concerned human being? I think to really help people in need requires more than just listen…

Thanks, Bearly. To answer your question, I think Saul is all of the above. Listening may not solve all problems, but it’s an important first step.