Vegetable Peelings: Revealing the Creative Process

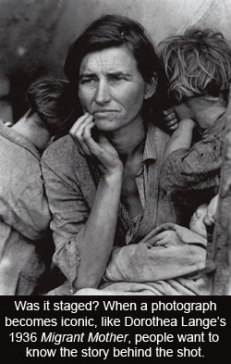

When a photograph becomes acclaimed, whether as journalism or art, questions can swirl around it. What’s the story—did the photographer capture the image in a moment of serendipity or as the result of patient labor? Were elements arranged to create more visual drama? If it features human subjects, were they willing participants or unwitting victims?

When a photograph becomes acclaimed, whether as journalism or art, questions can swirl around it. What’s the story—did the photographer capture the image in a moment of serendipity or as the result of patient labor? Were elements arranged to create more visual drama? If it features human subjects, were they willing participants or unwitting victims?

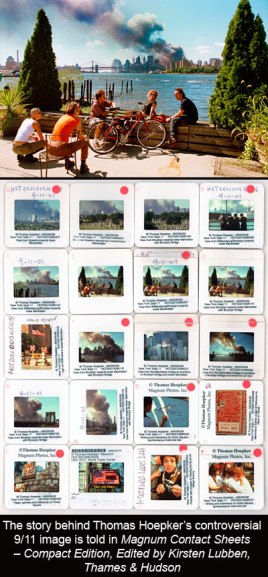

These kinds of questions have caused controversies to rage over all kinds of photographs. While perhaps the image to come in for the most sustained interrogation is Robert Capa’s The Falling Soldier (originally titled Loyalist Militiaman at the Moment of Death ), which has been debated endlessly, heavy scrutiny has also been directed at some famous Depression-era images , at almost every image by Diane Arbus , at Thomas Hoepker’s notorious image shot on 9/11 , and, most recently, at images shot through neighbors’ windows and presented as art .

So it’s interesting to see photographers’ processes revealed in two new books,

Magnum Contact Sheets

and

Photographers’ Sketchbooks

. Though the former was originally published in 2011, it has just been reissued in a “compact format”—which is something of a misnomer considering that the new edition weighs as much as a robust newborn baby.

So it’s interesting to see photographers’ processes revealed in two new books,

Magnum Contact Sheets

and

Photographers’ Sketchbooks

. Though the former was originally published in 2011, it has just been reissued in a “compact format”—which is something of a misnomer considering that the new edition weighs as much as a robust newborn baby.

Both books shed light on the creative process, and there are similarities between them but also differences. While Magnum Contact Sheets is mostly interested in revealing what happened directly before and after the capture of a successful single image, Photographers’ Sketchbooks takes a wider-angle look at the creative process. Also, while the members of Magnum Photos are mostly (but not exclusively) photojournalists, the contributors to Photographers’ Sketchbooks come from all corners of the photographic world.

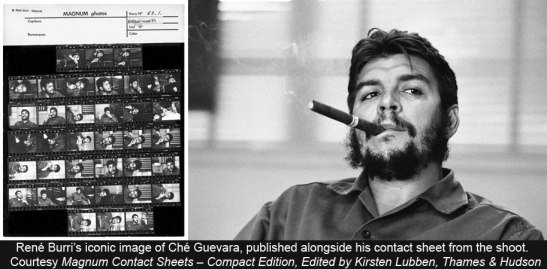

Since its inception in 1947, Magnum Photos has been known for the visual flair with which its members have captured cultural moments and current events. The list of famous images from the agency is long, from Robert Capa’s D-Day images of soldiers landing in Normandy to Steve McCurry’s Afghan Girl . And how about the iconic image of a cigar-chomping Ernesto ‘Ché’ Guevara by the great René Burri, who died earlier this week aged eighty-one?

Reading the stories behind some of these images is fascinating. About the Ché image, for example, Burri writes that the revolutionary was so focused on his discussion with an interviewer that in two hours, he never looked at the camera (this in confirmed by the contact sheet). In contrast, Eve Arnold writes of her famous portrait of Malcolm X that the subject was a “clever showman and apparently knowledgeable about how he could use pictures and the press to tell his story… With the photos of himself, he was professional and imaginative.”

Reading the stories behind some of these images is fascinating. About the Ché image, for example, Burri writes that the revolutionary was so focused on his discussion with an interviewer that in two hours, he never looked at the camera (this in confirmed by the contact sheet). In contrast, Eve Arnold writes of her famous portrait of Malcolm X that the subject was a “clever showman and apparently knowledgeable about how he could use pictures and the press to tell his story… With the photos of himself, he was professional and imaginative.”

I was also captivated by the story behind Philippe Halsman’s famous portrait of Salvador Dali, Dali Atomicus . These days, an image like that would be composited in Photoshop, but Halsman shot it in photography’s Paleolithic era, otherwise known as 1948. The text reveals that, “with military precision, Halsman counted to three, his assistants launched three cats and a bucket of water into the air, then at four, Dali jumped and Halsman took a picture before everything hit the floor.” Following each take, Halsman went into the darkroom to develop the film and check the result, and “six hours and twenty-eight throws later, the result satisfied my striving for perfection.” One has to wonder how the cats felt, though as Halsman reports, at the end “my assistants and I were wet, dirty and near complete exhaustion—only the cats still looked like new.”

Indeed, almost all of the images showcased in Magnum Contact Sheets were shot on film, which lends a warts-and-all flavor to the presentation. Digital images can be deleted or edited in-camera, but with film there’s nowhere to hide. “It’s generally rather depressing to look at my contacts—one always has great expectations, and they’re not always fulfilled,” writes Elliott Erwitt, and for Henri Cartier-Bresson, “A contact sheet is full of erasures, full of detritus. A photo exhibition or a book is an invitation to a meal, and it is not customary to make guests poke their noses into the pots and pans, and even less into the buckets of peelings.”

We should be grateful, then, for the willingness of these photographers to show us their vegetable peelings. In some instances, the contacts are oddly reassuring, showing us that great photographers are not great all the time. In others, they shed new light on an image we thought we knew, enhancing its power and significance.

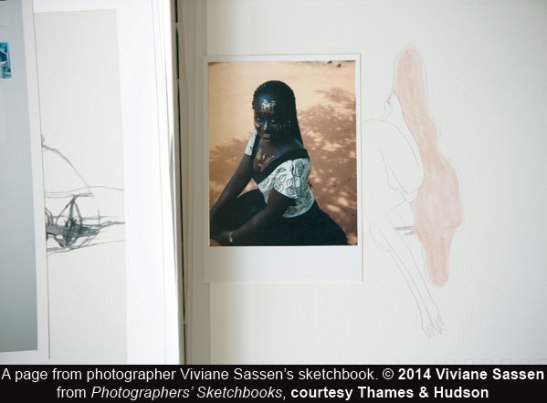

By contrast, Photographers’ Sketchbooks feels more improvisational—which is part of its point and its charm. In the words of co-editor Stephen McLaren, it is “a celebration of the boundless possibilities for creativity in the modern photographic era.” Ranging across genres, it showcases talents from the disparate worlds of art, journalistic and fashion photography, such as Roger Ballen, Susan Meiselas, Viviane Sassen and Alec Soth. The concept of “sketchbook” is wide-ranging too: the photographers contribute everything from written journal pages to doodles, maps and paintings.

As in

Magnum Contact Sheets

, there are some good stories to be had in

Photographers’ Sketchbooks

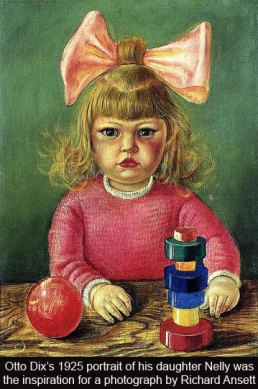

. I was moved by Richard Ansett’s story of how he modeled two portraits of Marie Louise, a girl diagnosed with a brain tumor, on Otto Dix’s paintings of his daughter, and how this informed his subsequent work. It’s also fascinating to read about the ad-hoc, collaborative process behind Roger Ballen’s beautifully eerie black-and-white images. These images are meant to be mysterious, but somehow, reading the backstory of an image of a homeless man cuddling a plastic sex doll under a bed didn’t detract from its mystery. To know that this strange image was taken at the subject’s request just added to its psychological pull.

As in

Magnum Contact Sheets

, there are some good stories to be had in

Photographers’ Sketchbooks

. I was moved by Richard Ansett’s story of how he modeled two portraits of Marie Louise, a girl diagnosed with a brain tumor, on Otto Dix’s paintings of his daughter, and how this informed his subsequent work. It’s also fascinating to read about the ad-hoc, collaborative process behind Roger Ballen’s beautifully eerie black-and-white images. These images are meant to be mysterious, but somehow, reading the backstory of an image of a homeless man cuddling a plastic sex doll under a bed didn’t detract from its mystery. To know that this strange image was taken at the subject’s request just added to its psychological pull.

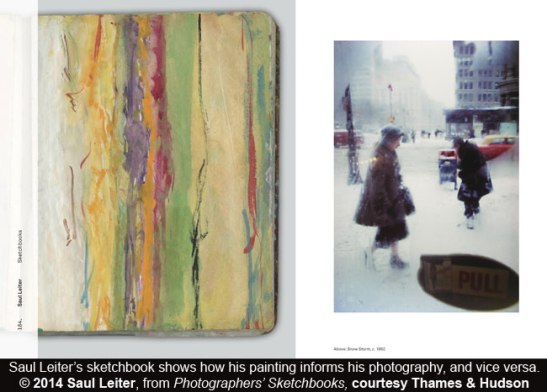

Not all of the sections are this interesting. It doesn’t particularly add to my experience, for example, to know that Susan Meiselas and Trent Parke keep notebooks in which they jot down details about their subjects (I’d be surprised if they didn’t). However, the notebooks of Robin Cracknell and Saul Leiter are delicate and lovely, works of art in their own right. Cracknell’s images of his son, combined with diagrams and words, reveal a father’s struggle to navigate a difficult divorce. Leiter, who died in 2013, always wanted his painting notebooks to be published, so people would know he wasn’t just “that elderly American photographer who had recently been rediscovered.” Shown here, the notebooks confirm how Leiter’s painting informed his photography, and vice versa. As his assistant Margit Erb says, “He put things into the abstract, he paid attention to color, he threw foregrounds out of focus…he applied a painterly mentality that the photography world had not seen.”

It’s interesting, too, to see how some photographers use their sketchbooks to dream. While shooting a project about the Mafia in Sicily, just before visiting a market, Mimi Mollica doodled a swordfish head with the price of the fish stuck through its eye; later, in the market, he saw the real thing. Conversely, for Viviane Sassen, expressive doodling takes her away from realism and toward the subconscious. As she puts it, drawing “has magic, sensitivity and a river of possibilities that are the opposite of the realistic world of photography.”

Though Photographers’ Sketchbooks feels more raw and risky than Magnum Contact Sheets , both books are very much in tune with our “sharing” age, when every mood and meal has become ripe for documentation, and we’re fascinated by details. Is there such a thing as too much sharing? It could be argued that sharing one’s sketches and also-rans connotes a certain self-regard; you have to have a healthy ego to believe they are of consequence. On the other hand, Henri Cartier’s Bresson’s vegetable peelings are a lot more interesting than many people’s Ratatouille Provençale . Getting a peek at them, and those of other distinguished image-makers in these two books, delivers its own intense thrill.

6 comments on “ Vegetable Peelings: Revealing the Creative Process ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Magnum Contact Sheets looks very interesting, and a clever idea by its author. A timely book review for the upcoming Christmas shopping season! Thanks, Sarah, for the peek inside — reassuring before shelling out GBP30 for the book, (plus maybe more for a strengthened coffee table).

Hearing the stories behind a shot, and seeing the process unfold until the moment it all came together in a great photograph is fascinating. In a world where everyone is a photographer, I’m looking forward to seeing and hearing more about the process from great thinking photographers in Magnum Contact Sheets

Great post. I had a photography tutor years ago who was dead against showing your contact sheets to anybody else. He always said that it was showing your failures to the world. In other art forms (sculpture, fine art etc.) you only ever get to see the finished work that the artist is happy with – you never see the versions that didn’t work out along the way.

But of course its great to see the creative process in action, something that contact sheets are particularly good at demonstrating.

Great post and great review, Sarah! Both books look extremely interesting, in their own way. Will add them to my list.

Reblogged this on Oxford School of Photography and commented:

This is a interesting and accessible article and one that addresses question often raised in our more advanced courses like Intermediate photography, here is a link to that http://www.oxfordschoolofphotography.co.uk/intermediate.html

Thanks for the reblog!