The Earth We Tread On: An Interview with Scott Strazzante

Back in 2008, I interviewed photographer Scott Strazzante for Photo District News when his project Common Ground was—if you’ll pardon the pun—getting off the ground. Interviewing photographers can be hit-or-miss: not everyone who produces great visual work is capable of talking about it well. So it was a plus when Strazzante turned out to be not only a great visual communicator but also thoughtful and articulate.

It had been a good year for Strazzante. He’d won the Community Awareness award at the Pictures of the Year International (PoYI) contest, and was discussing having a documentary video made by the acclaimed company MediaStorm . Previously, his Common Ground work had been published in National Geographic and in Mother Jones , where it was accompanied by an essay by acclaimed novelist Jane Smiley. All pretty good for a project that owed its life to pure serendipity.

Recently published in book form, Common Ground tells the story of two families, the Cagwins and the Grabenhofers, who inhabit the same land at different times. Harlow and Jean Cagwin work hard to farm the land and raise Angus cattle for beef, but eventually have to leave when Harlow’s health fails. The Grabenhofers are one of many families occupying the bland suburban subdivision created after the Cagwins sell the land to a developer.

Before and After: the same land as a farm and a suburban subdivision. Image 2014 © Scott Strazzante, from Common Ground, PSG Books

Strazzante had never intended to do a before-and-after essay, but found the project evolving after a chance meeting with resident Amanda Grabenhofer. Still, it wasn’t until he took a picture of the Grabenhofers’ sons horsing around with a rope on their lawn that Common Ground really took off. Something about the image reminded Strazzante of one he’d taken of Harlow Cagwin wrestling with his dog. He opened up Photoshop and laid the images side-by-side as a diptych, and a lightbulb fired: he began to see all kinds of echoes and correspondences between other images.

The diptych that inspired Common Ground. Image 2014 © Scott Strazzante, from Common Ground, PSG Books (click all diptychs to see larger versions)

The resulting diptychs are delightful and surprising, showing the passage of time and the marks humans leave on the earth, and confounding our expectations about both rural bliss and suburban anomie. The book is very even-handed: Strazzante makes it clear that he’s not out to idealize or demonize anyone. A former subdivision resident himself, he strongly believes that “people can still have culturally rich lives in an aluminum-sided house.”

Last week, Strazzante spoke to The Literate Lens from his new home in San Francisco, where he recently moved to work at the

San Francisco Chronicle

after a long career with the

Chicago Tribune

.

Last week, Strazzante spoke to The Literate Lens from his new home in San Francisco, where he recently moved to work at the

San Francisco Chronicle

after a long career with the

Chicago Tribune

.

What was the initial assignment that sent you to Harlow and Jean Cagwin’s farm to photograph in 1994?

I was working for the Daily Southtown , a newspaper based in the south suburbs of Chicago, and I was assigned a story on people who were raising animals in Homer Township, an area about 30 miles south-west of the city. I photographed four places: there was a man raising wolves for educational purposes, someone who had a llama farm, and someone who raised horses. And then there were the Cagwins, who raised Angus cattle for beef. I showed up there in May 1994 and spent three hours with them while they were trying to vaccinate a calf. Harlow was 71, Jean was in her early 60s, and they didn’t have children…

…I found it fascinating that they were senior citizen cattle farmers, and the place was a bit run-down and had so many visual possibilities. So on my way out, I asked if I could stop by some other time. They said yes. My days off work were Sunday and Monday, and I was a single dad with young kids, so I’d go over there on Mondays when my kids were in daycare. I didn’t have any grand plan, just thought of it as hanging out there. It was an escape from my unexciting life at the paper, where I never got the opportunity to do in-depth photo stories. This was like giving myself a storytelling workshop.

At what point did it turn into a different kind of story, when Harlow and Jean sold the land to a developer who was going to turn it into a subdivision?

In the late 1990s, Harlow’s health started deteriorating, and there were whispers of the farm being sold. That’s when I started thinking it might be more than a personal project. The Cagwins sold the farm in 2001, then stayed on for a year, selling the cattle and tying up loose ends. I figured that once I’d photographed Harlow in front of his house while it was getting torn down, the story was over. But then I started to be interested in the process of what was happening on the land. They were already starting to build the subdivision before the Cagwins moved out. After the Cagwins left, I’d occasionally drive by and get some shots.

Harlow Cagwin watches his house being torn down to make way for a subdivision. Image 2014 © Scott Strazzante, from Common Ground, PSG Books

And then fate intervened…

Yes! I’m not super-proactive, I tend to let things come to me. So in March 2007, I was speaking to a photography class at the College of DuPage, and I showed some images from the farm. Afterward, I was approached by one of the students, a woman named Amanda Grabenhofer, who told me she lived in the subdivision that had replaced the Cagwins’ farm. She invited me out to an Easter party there, and I met all the families on her cul-de-sac, which was great because I could introduce myself and ask permission to photograph, and then if I showed up, nobody would be saying, Who’s that creepy guy with the camera? Originally, I’d thought to do a story on the whole cul-de-sac, but I found myself gravitating toward the Grabenhofers. In the final edit of the book there are pictures of the subdivision that feature other families, but in my mind it’s still a book about the Cagwins and the Grabenhofers.

Buckets take on different meanings in this diptych of life on the farm and on the subdivision that replaced it. Image 2014 © Scott Strazzante, from Common Ground, PSG Books

When I interviewed you in 2008 for Photo District News , Common Ground was a set of diptychs contrasting the two families’ ways of life. In the book, though, there’s a mixture of diptychs with more traditional narrative photojournalism. How was that format arrived at?

I actually wanted the book to have more diptychs. For me, Common Ground is about diptychs, about comparing and contrasting the two ways of life. In fact, one version of the book was designed with all diptychs, but the feeling was that it was too much. And even for me, when I got to the twenty-second diptych, it started getting a bit old. I think that for a general audience, it’s better to have some variety. However, I’m going to be putting together a website of about fifty or sixty diptychs, so that people will have a place to see them.

So what was the process of editing and deciding not to make the whole book diptychs?

I worked with Mike Davis, a brilliant photo editor who used to be at National Geographic , and before that was in Chicago at my newspaper group. If you ask me, he’s one of the top minds in the business. Photographers aren’t very good at editing their own work: we’ll give an image a lot of play because of external factors like how long it took to get it. Mike isn’t super-collaborative, but I recognized that if I was going to hand over the edit to him, I had to give up ownership. He’s operating on a different level; there’s nothing in Common Ground that’s there by accident. I’m proud and happy that he’s my friend and he did this for me. The older I’ve gotten, the better I’ve gotten at letting go.

You’ve been very clear that this project doesn’t have an agenda—but did you come to it with any preconceptions about farming or subdivisions?

When I was a kid, my grandfather owned a small farm up in Michigan. I’d go up there as a kid, fish in the lake, and hang out with other kids. I have great, great memories of it. I grew up near steel mills in an urban environment, so I was totally drawn to the Cagwin farm when I had the opportunity to be there. As far as the suburbs go, when I got married in 1991, my wife and I bought a house in a subdivision in Chicago, and that was my existence. I’m a liberal person and not a fan of suburbs per se, but I also know that the people living on them are usually good people just trying to live their lives, and I don’t want to denigrate them just because they’re living in the suburbs. We all have our biases, but as a photojournalist you’re trained to overcome those.

Children in the subdivision act out a fantasy of farm life. Image 2014 © Scott Strazzante, from Common Ground, PSG Books

What do you like most about doing a narrative photo-story as opposed to spot news?

When you do a longer story, each photo should push the story forward, but you don’t have to wow people with every image. Sometimes there’s room for a one that’s simply pretty, or informational. You can relax and explore a person’s character, show who they are in subtle, quiet moments. Still photographs can a bit mysterious, and viewers tend to fill in the gaps and project their own experience onto the images, similar to reading a novel. That works particularly well with Common Ground because it’s not a piece of advocacy: I’m not trying to tell people how to think, or to say that subdivisions are bad and farming is good. It’s a historical document, showing daily life in a place. And that’s something I think newspapers are bad at. We’re there when there’s an explosion, or if it’s the World Series, but when are we ever just in someone’s kitchen as they’re making dinner?

Saying Grace: The Cagwins and the Grabenhofers eat dinner. Image 2014 © Scott Strazzante, from Common Ground, PSG Books

Harlow Cagwin didn’t live to see the book, but you got coverage and awards for the project while he was alive, and there was a documentary film done by MediaStorm. What was his response to the work?

He and Jean were thrilled. He was alive when it ran in National Geographic , he saw the MediaStorm film, and the work had run in the Chicago Tribune several times. I’m super-disappointed he wasn’t able to see the book. He wasn’t a man of many words, he was a bit gruff on the outside. But Jean let me know that he loved having me around and felt very validated that I’d shown the world how hard he worked. There was just one image he didn’t like, of him laying on his bed, exhausted. I think he saw his mortality in it. But otherwise he and Jean had a pretty good sense of humor about the images. Jean wouldn’t let me go upstairs; she was worried that everything was untidy. The Grabenhofers were totally different. Amanda would say, Shoot whatever you want—it’s daily life.

Harlow Cagwin lies on his bed; Aiden Grabenhofer flips onto his sister’s bed. Image 2014 © Scott Strazzante, from Common Ground, PSG Books

You were shut out of certain photo contests because the rules were narrow and diptychs weren’t allowed. Has that changed at all since then?

No! The PoYI contest has a rule that there are no diptychs allowed, and that rule came into place when I submitted my project. I think it’s disheartening how slowly the industry and contests will take up anything that’s progressive or a bit different. Mobile photography is such a huge part of everyone’s lives now, and contests are still acting as if it’s not professional. It’s fine to use a point-and-shoot Barbie camera, a Holga, a Lensbaby lens, but cameraphones are beyond the pale. I think that’s dumb. People should realize that cameraphone photography is not going away, and embrace it. There should be a cameraphone category in every major contest.

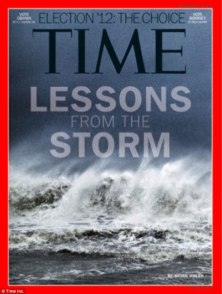

Especially since cameraphone images have been used in a lot of major publications. Benjamin Lowy’s iPhone image from Hurricane Sandy made the front cover of TIME…

Especially since cameraphone images have been used in a lot of major publications. Benjamin Lowy’s iPhone image from Hurricane Sandy made the front cover of TIME…

Absolutely. It’s just a camera! A lot of this is fear-based, I think. The New York Times ran reader-generated Instagrams on the front of their paper the other day, and I think that a lot of photographers see that and think, We’re going to lose our jobs! But it’s really about the skill you bring to the tool.

And the relationships. You obviously became close to the Cagwins and the Grabenhofers…

Definitely. The Cagwins had no children, and at times I felt like a surrogate son. I’d bring my children with me to play on the farm. I still try to visit Jean as much as I can. It was more than a photographer-subject relationship: I love them, and will always love them. When I won the Community Awareness award at the PoYI contest, the Grabenhofers came to the awards. I’m sure I’ll be photographing all their kids’ weddings!

Scott Strazzante photographs the Cagwins (left, by Jon Lowenstein) and the Grabenhofers (right, by Amanda Grabenhofer). Images 2014, from Common Ground, PSG Books

You started doing a photo blog when you were at the Chicago Tribune , and you’re now doing one at the San Francisco Chronicle . What’s that like—do you enjoy writing about images?

I do enjoy sharing my thoughts. I’m an over-sharer—I’ll share my entire life with anyone! A lot of young people might think I’m unapproachable because I’ve won some prizes, but one of my main goals is to show people that the level I’ve attained is achievable. When I was young, I worked with a veteran photojournalist called Rob Finch, and when he won the Photographer of the Year award, it made me feel that nothing was holding me back from doing that too. I’m not so special, I have some talent, but it’s all attainable. I’d like to show young photographers that their vision is valuable; that they can stay in their own neighborhood and do a long-term project and get attention for it. You don’t have to be a war photographer and go to Ukraine or Afghanistan. For me, this is the best work I’ll ever do, it’s the work of my career, and I won’t short-change it.

Fourteen years after he began photographing the Cagwins, Strazzante introduced them to the Grabenhofers. Image 2014 © Scott Strazzante, from Common Ground, PSG Books

38 comments on “ The Earth We Tread On: An Interview with Scott Strazzante ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Fascinating, Sarah. And Strazzante’s personality so refreshing. The fact that he doesn’t pass judgement on the changing landscape is admirable. Strazzante mentions that he would be “putting together a website of about fifty or sixty diptychs, so that people will have a place to see them.” I couldn’t find it online. Do you happen to know if they’re up yet, and if so, how I would find them?

Thank you, Amy! To my knowledge, Scott has not yet put together the website with diptychs. I’ll let you know if there’s an update!

Reblogged this on .

I am a fan of Scott and count myself fortunate to have worked a bit with him at two points, many years apart, in our careers. Thank you for posting your interview. I enjoyed learning more about Scott.

My pleasure, just lori!

Reblogged this on Mobile world .

Thank you!

Reblogged this on imaz78 .

Thanks for the shout-out!

Reblogged this on sanjaynp1987 and commented:

Earth

Great, thanks!

Nice blog!

Thank you so much!

Reblogged this on ctaskin20 and commented:

So True

Thanks!

Beautiful Sarah, look forward to your next post. Merci!

Thanks for stopping by!

Such an enjoyable and refreshing read! As someone who is just learning the basics of photography, I found your post to be both fascinating and inspiring. It brought me back to what I want to really do with my developing photography skills – to tell stories. Thank you (and Scott) for this.

You’re so welcome! Thanks for visiting and taking the time to comment. All the best with your work.

This subject hits close to home as we, too, watch acre after acre of agricultural land being gobbled up by suburbs. As neutral as one can photograph such a story it’s impossible not to feel a little ache when you view it.

Great interview, Sarah!

Thanks, drawandshoot! May there always be beautiful nature for you to photograph 🙂

That’s just what I thought when I looked at the photo of Harlow and Jean being introduced to the Grabenhofers. Seeing the suburban housing put up where he used to farm the land, surely must’ve pulled on his heartstrings,

Wonderful story and photographs. I must buy this book.

Reblogged this on sugarbaby56 .

Thank you!

Great! Looking forward to your next post 🙂

Thank you for sharing this, i really enjoyed reading it

You’re welcome, Twillingart.

Thank you for this blog. It is inspiring.

You’re very welcome! Thanks for taking the time to comment.

Reblogged this on Art & Design without Frontiers .

Great, thanks.

Great.

I am living on an ex dairy farm now and the barns cost a lot to maintain but I do my best to keep them alive.

Thanks for the comment, Milton. I bet those barns are beautiful!

Reblogged this on The Home Orbit and commented:

What a great story on two different uses of the same piece of land.

Thanks for the reblog and for your nice comment, The Home Orbit!

Great story. It is interesting to see how our ever expanding global population is eating up nature and the land that actually feeds us.

Great Story! Thanks!

https://alittlepieceofearthblog.wordpress.com/