Reconsidering Robert Doisneau

One of the great things about reviewing books is that, every once in a while, a package arrives that contains a wonderful surprise. And hallelujah for that, because those of us who write about books certainly aren’t in it for the money, fame and awards.

One of the great things about reviewing books is that, every once in a while, a package arrives that contains a wonderful surprise. And hallelujah for that, because those of us who write about books certainly aren’t in it for the money, fame and awards.

This week, the gem in question was a new book called The Best of Doisneau: Paris . The book, which is only just bigger than a paperback novel, is intimate and accessible, and a great bargain at $12.95—frankly, I wish more photography books were published at this size. Curated by Doisneau’s daughters, the book features thirty previously unpublished images along with many of Doisneau’s greatest hits. The print quality is excellent, and there were only one or two crowd scene photographs where I missed having a larger format.

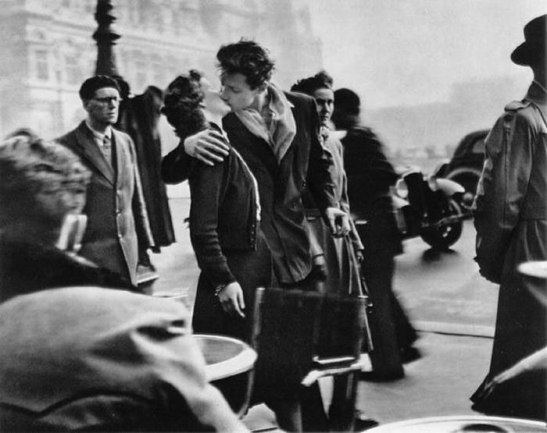

If, like me, you know Doisneau mostly through his well-known image The Kiss at the Hotel de Ville , and the minor controversy that erupted when it emerged that the image was semi-staged, there’s a lot to uncover here. During his lifetime, Doisneau captured a lot of history (such as French women voting for the first time in—shock, horror—1945), took portraits of many French celebrities, and created some intriguing photomontages.

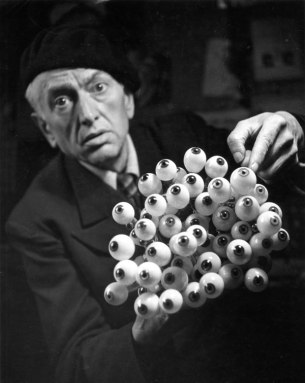

But it was really the spontaneous, serendipitous street image at which he excelled. A contemporary of Henri Cartier-Bresson , Doisneau found many of his own decisive moments as he prowled Paris with his Leica. Where he sometimes differs from Cartier-Bresson is in his more obvious sense of the absurd—which brings to mind the work of other master photo-humorists like Elliott Erwitt and Richard Kalvar.

Take, for example, a duo of images featuring statues. In the first, Venus Gone Bust , workers are shown moving a male-looking statue onto a place on a plinth—a move that, for no apparent reason, involves two of them putting their hands on the statue’s oddly prominent breasts. The other, Helicopters, Tuileries Gardens , shows a statue of the Three Graces liberally adorned with bird excrement, and above, in the sky, four military helicopters. Was Doisneau commenting on homoeroticism and the military-industrial complex in these images, or just enjoying their absurdity? Both, I would hazard a guess.

Doisneau was also a master of the written title, and many of his titles serve to add to the humor, or pathos, in an image. In one hilarious image, a well-dressed old gent is observed backstage with a topless showgirl: while she looks into his eyes, he stares fixedly at her breasts. The title— Respectful Homage— is ironic compression at its best. In an image featuring a different kind of gaze, a beret-clad man looks thoughtfully at a pale calf’s head hanging outside a butcher’s shop. By titling the image The Innocent, Doisneau gives it a poignant, almost biblical, undertone.

Another pleasure of this book is that it includes several pages of Doisneau’s journal entries, which are as tart and precise as his images. Of his tendency to capture moments of warmth and affection, Doisneau writes, “The world I was trying to show was one where I would have felt right… where I’d find the kindness I was seeking. My photos were a kind of proof that such a world could exist.” Of his long kinship with Paris, he writes, “I…have polished the city’s furnishings so often that, for the first time in my life, I feel a vague sense of ownership. I’d nevertheless like to remain one of those rare, broad-minded owners who always leaves the door wide open.”

Before he died in 1994, Doisneau lived to observe many changes to his beloved city, including a building boom in the 1970s that replaced graceful old buildings with beige tower blocks and reflective mirror-glass. Of the new landscape, he writes despairingly, “Cubes, squares, rectangles. Everything’s straight, everything’s even. Clutter has been outlawed. But a little disorder is a good thing. That’s where poetry lurks.” On the other hand, he admits (with refreshing honesty) that he has profited from the developers’ frenzy. “The demolishers have been my partners in crime. I’m grateful to those scenery-snatchers, because their boldness has lent my old pictures much more value.”

As for that controversy over The Kiss —well, it’s nice to see here that Doisneau had a lifelong preoccupation with public displays of affection. The earliest example in the book shows a woman holding a sleeping man as they take refuge in the Paris metro during a bomb alert—shot in 1942, eight years before The Kiss. And there are plenty more, especially of dancing couples—including what must have been a bold image, in 1951, of a white woman and a black man dancing in a bebop club.

With all this love and tolerance, it’s tempting to write Doisneau off as a sentimentalist—which is why I think he is regarded as a somewhat lesser artist than Cartier-Bresson. But there’s some proof here that, despite his desire to find evidence of human kindness, Doisneau wasn’t always so starry-eyed. Consider, for example, a wonderful 1954 image, in which some oafish-looking humans surround a tiny boxing ring where a well-dressed monkey sits with Buddha-like serenity. The title— Higher Species —is eloquent.

Still, it seems Doisneau was more often than not a glass-half-full kind of guy. “There are days when the mere act of seeing feels like pure joy,” he wrote in a journal entry. “One-hundredth of a second here, one-hundredth of a second there: added all together that still makes only one, two, maybe three seconds snatched from eternity.” Who can blame him for using his seconds to capture beauty, absurdity and charm?

—————————————————————-

To purchase The Best of Doisneau: Paris from Amazon.com, click here .

6 comments on “ Reconsidering Robert Doisneau ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Hi Sarah:

Great review! I posted it here:

I remember seeing another book of Doisneau’s work recently which included photos from the French Resistance in 1940’s Paris. Seems like they had a few in the book you reviewed as well.

My wife has a large poster of the “Kiss at the Hotel de Ville” just above where her desk is that she uses when she works from home. That’s what photography is all about. Making an impact in someone’s home or life!

All the best, Andrew

Thanks, Andrew! Glad you could stop by. There aren’t too many wartime images in this book, but there are plenty of other greats. Unfortunately the selection of press images was very limited and I couldn’t feature some of the ones I wrote about.

Great review Sarah – I think you’er absolutely spot on with the observation about Doisneau being a glass-half-full character. HCB’s intensity comes across in his imagery and he had a very different view of the world. Doisneau was more complex and nuanced – great piece of writing.

Thanks PP!

Robert Doisneau was who I chose to be my “Famous Photographer Mentor” in high school. Basically we all picked a noted photographer whose technique we wanted to mimic and Doisneau was my main man 🙂 I will have to check this book out. Thank you!

Great choice of mentor, underthebubbles!