At Home in the World: Two Documentaries

If beauty is in the eye of the beholder, works of art surely are too. We see them in the context of our lives, affected by whatever emotional weather is swirling around us at that moment. We evaluate them according to a complex metric that blends judgment with experience, latent knowledge, taste—and other more banal things, like Twitter and Pinterest.

So I found it interesting, this last week, when I saw two documentary movies that were almost polar opposites, but that each enriched my perceptions of the other. While one follows a photographer whose work takes him to the ends of the earth, the other is about a group of brothers who have lived their lives in near-isolation in New York City. Thematically, stylistically and tonally, the films couldn’t be more different. Yet both probe the dark side of human nature, and both show the redeeming power of creativity.

So I found it interesting, this last week, when I saw two documentary movies that were almost polar opposites, but that each enriched my perceptions of the other. While one follows a photographer whose work takes him to the ends of the earth, the other is about a group of brothers who have lived their lives in near-isolation in New York City. Thematically, stylistically and tonally, the films couldn’t be more different. Yet both probe the dark side of human nature, and both show the redeeming power of creativity.

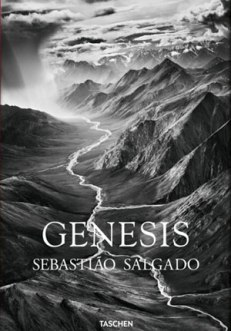

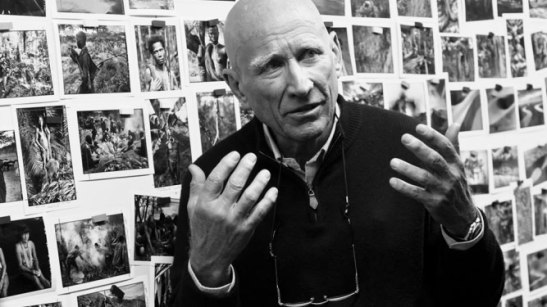

The Salt of the Earth celebrates the work of the famous photographer Sebastiao Salgado. Born in Brazil and based in Paris, Salgado does long-term, self-assigned projects that tackle huge themes like migration, workers and drought. He is one of very few photographers who can work on this scale, one of a handful whose name is recognized outside the photo world.

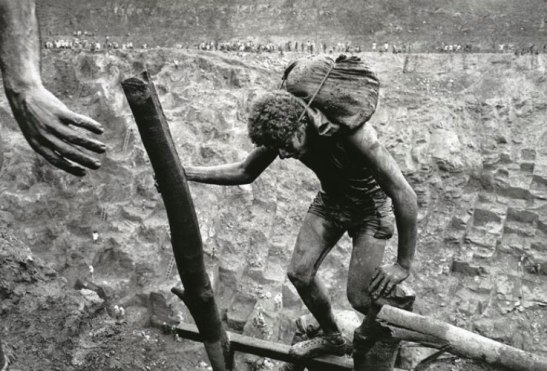

How do you achieve such rank? By taking jaw-dropping photographs, for a start. Salgado’s breakthrough came in the 1980s, when his images from a Brazilian gold mine shocked the world. He had captured a scene of biblical dimension, as tens of thousands of workers streamed, ant-like, to the bottom of a huge pit, then climbed rickety ladders with bags of dirt on their backs. “I saw unfolding before me the history of mankind—the building of the pyramids, the Tower of Babel, the mines of King Solomon,” Salgado says in the film. But unlike the slaves who built those structures, the men in the mines were freelancers drawn to a gold rush, “slaves only to the idea of getting rich.”

For a long time, Salgado—who initially trained as an economist—made it his business to witness atrocity. He photographed ethnic strife in the Balkans, burning oil wells in Kuwait, and famine in Niger. In the film’s most devastating sequence, he recalls crossing the border from the Democratic Republic of Congo into Rwanda just after the genocide, seeing bodies lining the roads all the way to Kigali.

Understandably, something snapped in him after that—“my soul was sick,” he says—and he started looking for causes for hope. His most recent project, Genesis , documents the natural world’s majesty, extending an implicit plea for us to preserve its wonder. As the film shows, he is equally at home hanging out with a remote indigenous tribe or with walruses in Antarctica. My favorite photograph from the series is a close-up of the hand of a Galapagos iguana, looking amazingly like a human hand covered in medieval armor. “Looking at this image, I understood that the iguana was my cousin,” he says.

It’s a great joy to see Salgado’s stupendous images on the big screen. One of the innovative features of this film (which was co-directed by Wim Wenders and Juliano Ribiero Salgado, the photographer’s son) is a technique Wenders developed to show Salgado talking about his work. He projected Salgado’s images onto a semi-transparent mirror, then seated the photographer behind the mirror and shot through it. As a result, we see Salgado’s talking head blended with the images he’s discussing, almost as if his memories are dreaming them into existence. With the interviewer out of sight, Salgado is able to look directly at each image and engage with it intensely.

If the film has a weakness, it’s that Wenders and the younger Salgado are a little too reserved and respectful. For example, they don’t take on the charge that has sometimes been leveled at Salgado, that his images aestheticize suffering (this is something of a minefield for humanitarian photographers). Perhaps they considered it beneath Salgado’s notice, but I would have been interested to hear his thoughts on the subject.

They also skimp on the relationship between Salgado and his son. Near the beginning, Juliano remembers growing up largely without his father, and perceiving him as “a kind of superhero” when he flew in to organize his negatives. There’s an interesting story here, about sacrifices made in pursuit of humanitarian goals, but the filmmakers don’t explore it. Instead, all we get is Juliano saying, as he accompanies his father on a

Genesis

expedition, “I wanted to find out who that man really was. The man I hadn’t really known as my father.”

They also skimp on the relationship between Salgado and his son. Near the beginning, Juliano remembers growing up largely without his father, and perceiving him as “a kind of superhero” when he flew in to organize his negatives. There’s an interesting story here, about sacrifices made in pursuit of humanitarian goals, but the filmmakers don’t explore it. Instead, all we get is Juliano saying, as he accompanies his father on a

Genesis

expedition, “I wanted to find out who that man really was. The man I hadn’t really known as my father.”

Then again, some kids might be better off without a paternal presence. Case in point: the Angulo brothers, who spent their youth locked up by their father in an East Village apartment. In her debut documentary, The Wolfpack , Crystal Moselle gets access to the six boys just as they’re coming of age and beginning to assert their independence, breaking free of their father’s tyrannical hold.

Narayana, Govinda, Jagadisa, Bhagavan, Mukunda and Krsna Angulo in THE WOLFPACK, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

There may be eight million stories in the naked city, but few are as odd as this one. The six Angulo brothers (and their mentally disabled sister) are the children of Susanne, a former Midwestern hippie, and Oscar, a Peruvian she met while hiking the Inca Trail. Back in the U.S., Susanne and Oscar landed in a Hare Krishna community, then in New York, where Oscar fulfilled his plan of breeding his own mini-tribe, each member possessed of long black hair and a Sanskrit name. In order to “protect” them, Oscar insisted that Mom and the kids stay locked in the apartment. In a good year, the family might get outside six times. One year, they never made it out at all.

Think you know how the story goes from there? Get ready for some surprises. Because although this is a story of abuse, it doesn’t follow the typical trajectory of such stories. Against all odds, the boys are bright, gentle and amazingly resourceful. Brought up on movies, obsessed with the likes of Tarantino and The Dark Knight , they spend hours on complex reenactments and mash-ups, complete with detailed costumes and make-up. Their confinement, in fact, has forced them to leverage their creativity and individual talents as they bond together.

Krsna, Jagadisa, Bhagavan, Mukunda, Narayana and Govinda Angulo in THE WOLFPACK, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

In one especially poignant scene, Mukunda, the third eldest brother, stares contemplatively out of the window while dressed in a Batman costume made from a cut-up yoga mat and cereal boxes (it’s amazingly authentic-looking). The lights of the city twinkle below him, yellow cabs stream to and fro, and there’s an exquisite irony in the fact that this all-powerful savior of Gotham can’t even leave his own apartment.

As it happens, this scene is a turning point: something crystallizes for Mukunda in that moment, and he musters the courage to leave the apartment and roam the neighborhood, wearing a homemade Michael Meyers mask. The expedition ends badly, with freaked-out passersby calling the police—but the spell is broken. After that, the six boys begin venturing out together, dressed in dark suits and shades, looking like a six-pack of skinny Blues Brothers.

Director Crystal Moselle on the set of THE WOLFPACK,

a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures. Photo credit: Megan Delaney

Like Wenders and Salgado junior, Moselle sidesteps some of the thornier issues her film brings up. There are no interviews with neighbors or social workers, no psychologists weighing in on why the brothers proved so resilient. There is no explanation of how the family, which lives on government handouts (Oscar refuses to work) can afford DVD players, computers and an extensive movie library. And although she gets Oscar and Susanne in front of the camera, Moselle is reluctant to press them too hard, probably because doing so would compromise her access. Though that’s understandable, it leaves some important questions dangling.

What shines through, though, is the brothers’ gentleness and creativity. This culminates in a wonderful sequence where one of them, Govinda, begins to make his own movie, a surreal fable about his odd family. A neighborhood girl called Chloe is conscripted to join the cast, and she performs her part with brio, fully drawn in to the brothers’ rich imaginative world.

Govinda’s movie might be a homespun affair, with cardboard sets and papier-mâché masks, its rough edges completely opposite to Salgado’s ultra-polished, authoritative work. But there’s passion there, and determination. And that—whether you go to the ends of the earth like Salgado or stay in a tiny room; whether your vision is focused outward or inward—is something no artist can afford to be without.

———————————————————–

The Wolfpack will screen at the Tribeca Film Festival on April 18, 20 and 22 (buy tickets here ) and will open theatrically on June 12.

The Salt of the Earth is currently on general release.

FURTHER RESOURCES

View the trailer for The Salt of the Earth here .

Sebastiao Salgado’s TED talk, The Silent Drama of Photography , is here .

The official movie site for The Wolfpack is here .

7 comments on “ At Home in the World: Two Documentaries ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

A fascinating comparison. Both chilling and curious. Like you, I’d be interested in gaining more insight into the relationships and circumstances of each. Terrific post!

I was excited to see this post as I had just seen the Salgado documentary (I’m a huge fan of his work) and had recently read about the fascinating story of the family in Wolfpack which I’m looking forward to–even if the film maker doesn’t dig deep.

While I have sympathy that the young Salgado didn’t grow up with his father present, I’d also point out that a huge sacrifice was made by Salgado’s wife, Lélia Wanick Salgado, who raised the children while supporting Salgado’s career. I would have liked to have heard more about her collaboration with Salgado which allowed him to go off and create the amazing photos he did, not to mention her idea of re-planting an entire forest. Who does that? And succeeds?!!

The Salgado’s are my heroes. Thank you Sarah. Great post!

Good point, Julie! I wanted to know more about Lélia too. I didn’t mention the amazing reforestation project they did, which was her idea, because I had two movies to discuss and you can’t get to everything. But I think it’s a wonderful example of putting your money where your mouth is (or where your photographs are). You should check out Salgado’s TED talk, which I link to at the end of the post. In it, he gives out some interesting nuggets about his background and family, and has some flashes of humor that I liked too.

Oh yes, I will definitely check out his TED talk.

One more thing I found interesting. I thought Salgado was kind of stand offish and well, grumpy when I saw him talk at UC Berkely back in the 90’s. I still admired him and his work greatly but I got such a strong feeling that he hated what he was doing at that very moment (having to talk to a room full of mostly privileged people who hadn’t given much thought to the overabundance of things, food, etc. they had access to on a daily basis). After seeing the documentary I realize it was during the time when he said his “soul was sick” and understandably so. I’m in even more awe of him that he recognized his sadness and was able to turn it around and continue to make amazing and hopeful photos bringing a sense of peace to himself and sharing that with the world. Jeez.

Sarah, Great post! Would love to see both of these films. Very intrigued by Wolfpack, and how the family survives.

Wonderful article.

I remember seeing a Salgado show 10 or 15 years ago at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. He’s an amazing photographer.

Reblogged this on gguyphotography and commented:

Another iconic documentary photographer of the 21st century, Sebastiao Salgado! His specialism is nature and environmental documentaries.