Legacy Keeper: An Interview with Mary Engel

The April issue of Photo District News features an article I wrote about managing photographers’ legacies . This is an important topic, but one that isn’t discussed or written about much. Photographers generate huge amounts of material that’s hard to organize and appraise: often they fail to do so, leaving a giant mess for their heirs.

The article was tough to write, due to legal and accounting issues that were difficult to understand and even harder to explain in a way that wouldn’t cause narcolepsy. But even hard-to-write articles can have a silver lining, and in this case the shiny bit was talking to Mary Engel—who manages the archives of her photographer parents, Ruth Orkin and Morris Engel —then, as a follow-up, going to visit her at the Orkin/Engel Archives in Union Square.

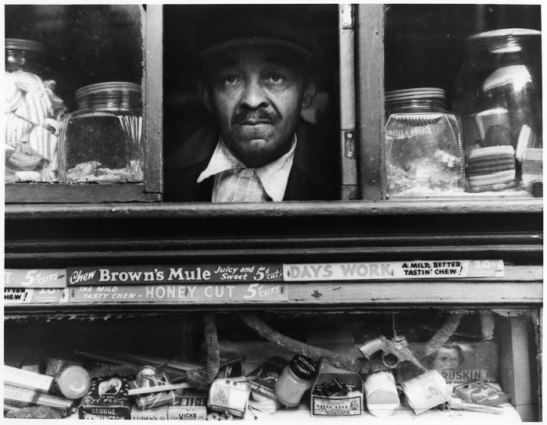

I’ve always loved the work of Ruth Orkin and Morris Engel. Both were connected with the socially-conscious school of documentary photography that sprang from the Photo League in the 1940s. Individually, they produced significant bodies of work, including Engel’s contributions to the Photo League’s Harlem Document , and Orkin’s book A World Through My Window . Together they made a feature film, Little Fugitive , which is credited as the first independent American movie, was nominated for an Oscar, and influenced John Cassavetes, Francois Truffaut and D.A. Pennebaker, among others.

I haven’t visited any other photographers’ archives, and had a hazy idea that I’d be walking into a spacious library, perhaps with mobile shelves on rails and a controlled climate. This turned out to be somewhat inaccurate: the Orkin/Engel archives are housed in a narrow room, perhaps eight by twenty feet, with materials piled on high shelves and other available surfaces. “Obviously I have the work in archival boxes, and I have good insurance,” Engel told me. “Anything else is expensive. I don’t know anyone who has the resources for climate control.”

When Orkin died in 1985, following a battle with cancer, Mary Engel was in her twenties. At first, she resisted the idea of managing her mother’s archive full-time: “It was too intense,” she said. But after a while, she realized that years of helping her mother—along with her experience as an advertising assistant at ARTnews magazine and in the agent training program at William Morris —was the perfect preparation for the job. “I thought, why represent all these crazy actors and writers?” she said. “Let me just represent my mom.”

It wasn’t easy in the beginning, though. Engel got some advice from Doon Arbus, who manages the estate of her mother Diane Arbus , but often found she was learning on the job. “How do you decide how much to license an image for?” she said. She would sometimes charge too little for a print, or send out a vintage print for reproduction, which was a mistake considering how valuable vintage prints would later become.

Orkin’s most famous image—one you’ve surely seen, even if you don’t know who took it—is An American Girl in Italy, 1951 . In it, a statuesque, dark-haired beauty saunters down a street in Florence, while men on either side ogle and call out to her. A document of its time, the image contrasts the self-assurance of a gutsy woman with the cheeky appreciation of a group of underemployed men.

The subject of the photograph, Ninalee Craig, met Orkin in Florence in 1951, when Orkin was on her way back from a LIFE assignment in Israel. “We were two young, carefree women, playing with the idea of a woman traveling alone,” Craig recently told the Guardian ’s column That’s me in the picture . Though feminists have read sexual harassment into the image, Craig and Engel resist that interpretation. “My expression is not one of distress, that is just how I stalked around the city,” Craig remembered.

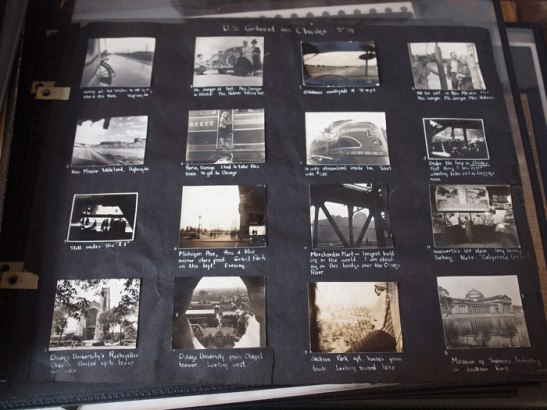

Orkin, too, was adventurous from a young age. It was a treat to look through some of her old materials at the archive, like the album she made about the cross-country cycle ride she did in 1939, when she was seventeen. “She had chutzpah,” Engel told me. “I don’t know why her parents let her go on that trip at seventeen, but they did—I think they just realized, she was who she was.”

Eventually, this free spirit did settle down. She married fellow-photographer Morris Engel, who had critiqued her images in a class, and the two became creative collaborators. Their debut movie, Little Fugitive , is credited as being the first independent American movie. “Everything was made by studios then, but this was truly independent—there was my dad, my mom and one other person,” Mary Engel recalled. To shoot on location in Coney Island, Engel built a handheld lightweight 35mm movie camera, allowing them to work fast and spontaneously. Years later, directors Truffaut and Cassavetes would copy their methods.

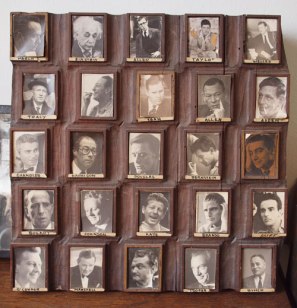

For a while after she married Engel, Orkin maintained an active career outside the home. Following her love of music, she went to Tanglewood and photographed luminaries like Leonard Bernstein and Aaron Copland, which grew into assignments photographing Hollywood stars and other celebrities. Twenty-five of these portraits sit, framed, on a board on Engel’s office desk.

Inevitably, though, once the couple had children, Orkin took on more domestic work (it was the 1950s, after all). In the Orkin-inspired chapter of her 2012 novel Eight Girls Taking Pictures , author Whitney Otto vividly imagines the journey made from globetrotting photojournalist to mother. “Some days it shamed her to want to be anywhere but home making jelly sandwiches and reading the same books that she had read a thousand times,” Otto writes. Drawn to her window, the Orkin character (here called Miri Marx) watches “the pedestrians and the sky, the trees, and the way countless windows lit up, wondering what was going on behind them.”

In the novel, as in real life, this watching leads to series of photographs that become a book called A World Through My Window , which symbolizes both the limitations imposed on women and Marx/Orkin’s ability to creatively subvert them. Seeing an exhibition of the work, an older female photographer in the novel understands that under its quietness lies a political statement. “The men only see what we do as sweet, sentimental, missing the meaning entirely as they view us as women who make photographs in our spare time,” she remarks.

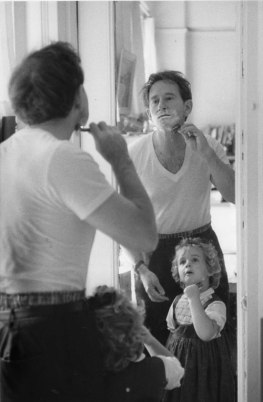

Engel said that, although her mother sometimes felt restricted by domestic responsibilities, she was a wonderful parent nonetheless. “She was into being a mother; she was around. I couldn’t do this job, spend all this time with her work, if I hadn’t had a real connection with her.” Engel also had a great connection with her father, who died in 2005. One of her favorite images in the archive shows her at age five, looking up at her dad and mimicking his actions as he shaves in front of a mirror.

These days, in addition to managing both her parents’ archives, Engel also runs the American Photography Archives Group (APAG) , a resource and support group for people who own or manage privately-held photography archives, which she founded in order to help people like herself who have inherited photographers’ archives. “So many of our members work full-time, and although getting bequeathed an archive is a wonderful legacy, it’s a huge responsibility,” she said. APAG offers regular meetings, seminars with experts, and online resources to help guide individuals through the intricacies of owning an archive.

For Engel, who has made archive management her career, the weight of responsibility is balanced by the satisfaction of seeing her parents’ work preserved and loved. It can be a hard business to run, she said, but she tries to approach it with her mother’s can-do spirit. “I remember, we’d go out on the street and she’d stop someone and say, I’m a photographer and you’re fascinating, can I take your picture?” she told me. “It embarrassed me at the time. But now, when I’m out in the world, I try to have that same confidence.”

————————————–

FURTHER RESOURCES

The Ruth Orkin Photo Archive is here .

The Morris Engel Archive is here .

The American Photography Archives Group is here .

My review of Whitney Otto’s Eight Girls Taking Pictures is here .

10 comments on “ Legacy Keeper: An Interview with Mary Engel ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Where would the world be without our legacy keepers. Eloquent and informative piece. I love history ….reflecting on important pieces of yesterday. Well done!

Sent from my iPad

>

Beautiful, informative piece as per usual. Thank you for continuing my photography education! Some more books to read 🙂

Thanks, Julia!

Enjoyed this very much. I do remember seeing that picture of the girl in Italy, I just don’t remember when. One day I’m looking forward to getting back into photography like I used to be; until then, these posts will keep my appetite whetted.

Thanks, smithaw50! Glad you’re enjoying the posts, and thanks for checking in.

Amazing article. An American girl in Italy was my favourite piece of art/photography when I was growing up. My Dad is an artist. You have made my day.

Thanks for your comment. Glad you enjoyed. I’m thrilled to have made your day!

such an interesting story!

Reblogged this on venus vegan and commented:

There are many causes we can fight for with veganism being one of them. Its crucial to remember that many people need our help. I’ve never been as enlightened in my life as I have this summer. I have read books and increased my awareness of the issues plaguing society. Sometimes it’s necessary to branch and see the things that other refuse to. I challenge you all to leave your comfort zones and learn about the struggles our brothers and sisters are facing.

This is such a cool look into the past. I really enjoyed it!