Boost of British: An Interview with James Hyman

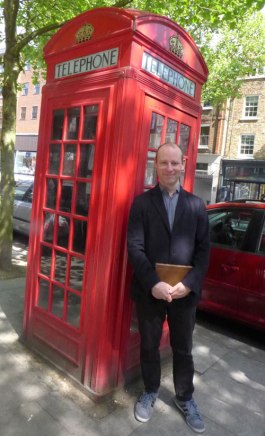

I don’t always follow my mother’s advice (sometimes to my detriment), but when she told me to call James Hyman, I got on it right away. Hyman is a unique figure in the British photography scene–a dealer, collector, and former academic, he has a finger in many pies. As such, he is perfectly placed to discuss a broad spectrum of issues that concern British photography and the photo world in general.

Recently, Hyman launched a website, Britishphotography.org , to showcase the impressive array of works that he and his wife Claire have collected. Right now, the site functions as an educational resource and promotional tool for British photography; in future, Hyman plans to expand on that base by funding photographers’ book projects and launching a new photography award.

Hyman also served on the advisory board for the inaugural Photo London fair, which took place last weekend and drew more than twenty thousand visitors. Though its dealers and speakers came from far and wide, the fair gave London a new (and perhaps overdue) focus as a photography destination. As the Financial Times noted , “among the plethora of new fairs, this one plugs a real gap, finally bringing a large, international photography event to the banks of the Thames.”

Which is all to the good, because, despite Britain’s place at the forefront of early photography through Fox Talbot’s invention of the calotype , British photography is not well known. Certainly, there are huge gaps in my knowledge of it, which is a glaring omission considering it’s my mother country. And so, since I happened to be in London recently (though sadly, couldn’t stay for Photo London), it was a perfect opportunity to sit down with Hyman and pick his brains about the new website, photo fairs and British photography in general.

What was your impetus for starting the website Britishphotography.org ?

When you first start collecting art, you tend to buy what you like. But at a certain point for me, it became not just about my heart but my head, about my desire to learn more. Part of doing my doctorate in art history was building a structure around a thesis. And I suppose, on a personal level, doing the website on British Photography is me trying to make sense of all this work that my wife, Claire, and I have collected. But, the bigger ambition, the reason to make this public, not just have a private database, is to spread the word, to use the collection as an educational resource. We are not an institution; it’s a personal collection. Nevertheless, the collection covers a lot of ground and hopefully by having lots of information as well as links to other websites, britishphotography.org will play a part in providing information about some great photographers and some amazing bodies of work.

I like the fact that you’ve organized the work into individual artist pages, but also in thematic groupings. Was that part of trying to make sense of it?

Yes. Artists generally want their work to be seen in isolation, which I respect, but it can be interesting to look at different approaches to the same subject. For example, if someone’s photographing working class people in Liverpool, are they a sympathetic insider or an outsider looking for a great image? Some of the work on the site is very empathic and humanist, some of it is cooler. I think that by juxtaposing those aesthetics, you can reveal things about what different artists are up to.

Who do you think are some of the most overlooked British photographers?

On the website, we’re trying to present a cross-section of British photography: social and conceptual documentary, landscape, more self-consciously artistic work. It’s a range. What’s familiar or unfamiliar has less to do with quality and more to do with fashion and shifts in tastes. For example, I think that in the 1970s there were some great photographers engaged with the English landscape. Paul Hill had a workshop in Derby called The Photographer’s Place that was fantastically dynamic and drew photographers from all over the world, including Minor White and Aaron Siskind. Along with Hill, people like John Blakemore and Thomas Joshua Cooper were doing incredible pictures derived from the British landscape, in a style influenced by Americans like White, Strand and Weston. It’s terrific work, but it isn’t as well-known as it should be.

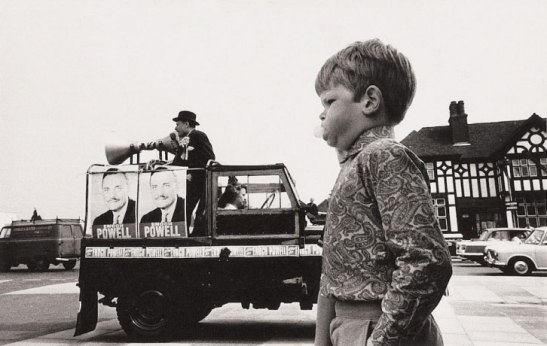

Enoch Powell and Bubblegum Boy, Wolverhampton, 1970, (c) Paul Hill, courtesy of the Hyman Collection

Does British photography have a national flavor?

I do feel there is a particularity about much that is produced here but it’s hard to articulate. I’ve recently been working on an A to Z of British Photography and began by suggesting that to try and characterize any nationality is perhaps too highly charged today. Instead we have tried to focus on the exceptional visions of a range of photographers. But clearly to the outside world we are seen in a particular way and the collection has pictures which address questions of national identity, self-identity and public perception. We have photographs that explore our fascination with royalty, the class system, the British Empire, fashion, punk, pubs, the countryside, the tourist industry, eccentricity….

You also have some interesting women photographers on the site: I hadn’t heard of Anna Fox, for example, and I really liked her work.

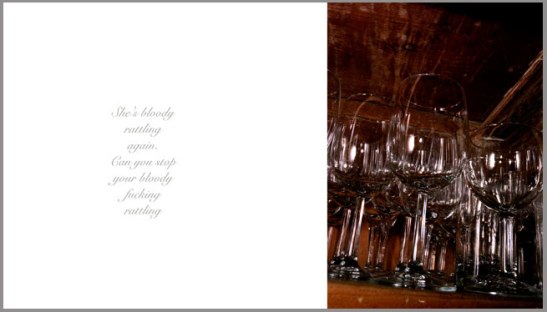

Yes, nearly half the photographs on the site are by women. In my opinion, Anna Fox is one of the really great contemporary British photographers. She has a lot of fascinating, different bodies of work. One of her great works is a tiny book, only about four inches across, called My Mother’s Cupboards and My Father’s Words . It shows these incredibly pristine, tidy shelves of possessions organized by her mother, and then these brutal, savage words from her father. It’s incredibly poignant and intimate, and it was the body of work that got me engaged with her.

From the series My Mother’s Cupboards, My Father’s Words, (c) Anna Fox, courtesy of the Hyman Collection

Recently, you asked Anna Fox and Andrew Bruce to make images using some artefacts you’d collected: puppets from the satirical 1980s British television show Spitting Image . Your gallery exhibited Fox’s photographs in the run-up to Britain’s recent general election, and they were dramatic and provocative, showing puppets of politicians like Margaret Thatcher and Michael Heseltine as worn out and expendable. First of all, what on earth made you buy those puppets, and secondly, what were some of the best reactions to the show?

Spitting Image puppets of Margaret Thatcher and her political peers. Image (c) Andrew Bruce and Anna Fox, courtesy of the Hyman Collection

Spitting Image was part of my childhood. It’s amazing to think that in the mid 1980s a quarter of the country would tune in to watch. Its satire of political figures, at a time when they were respected much more than they are today, was shocking. I’ve always been interested in politics so the chance to acquire several of the puppets was wonderful. What I hadn’t appreciated is that they were life size, wearing real suits. So once I’d got Margaret Thatcher and many of her government ministers, the challenge was working out what to do with them. Finally I suggested to Anna and Andrew that they photograph the puppets. I didn’t give them any suggestions and was surprised and shocked by the results. We received a huge amount of press coverage, which shows how much the program is still in our psyche. Each person who came in seemed to have a personal story or favorite moment that they were keen to share.

You just took part in the inaugural Photo London as a dealer, speaker and member of the advisory board. So why has London thrown its hat into the ring, and what distinguishes Photo London from other international photography fairs like the AIPAD photo show in New York and Paris Photo?

I’m on the board of both Photo London and AIPAD and exhibit at Paris Photo, and each fair has its own personality. AIPAD remains the best for historical material, Paris Photo remains the biggest and most comprehensive, but Photo London had an incredible buzz. It was a really amazing event: great galleries, a fabulous talks programme, a wonderful venue. There was real excitement. It was fantastic to see such enthusiasm. I think it surpassed everyone’s expectations. It was an amazing achievement for the first year of a fair.

I was interested to read, in an article about you in the British Journal of Photography, that Britain has a less active photography market than many other countries. Why do you think that is?

People consume photography in this country; they just don’t collect it. I think that’s to do with the history. In France, photography was the key art form in Surrealism; in America, Californians like Weston and Adams perfected prints that were beautifully mounted, signed and editioned. But in England, photographers like Bert Hardy and Grace Robertson showed their work in magazines. The tradition of consuming photography in print continues to this day, through photo books, which are popular here. The Tate Gallery now has a curator of photography, but they’re more comfortable buying for Tate Modern than they are for Tate Britain. They have a curator of Photography and International Art but they could really do with an equivalent position of Curator of Photography and British Art.

Does being a dealer and a collector present a conflict of interest?

No, but it’s an interesting position to be in. There are hardly any collectors in this country—so what has been to my advantage as a collector has been to my detriment as a dealer. It means that for the collection we’ve bought some fantastic photographs, but as a dealer, photographs are not easy to sell over here and we sell a high percentage of our photographs to foreign museums. If I were following the market, I wouldn’t be dealing in photographs in London right now. But this is my home; I went to school here, I live here. I think you have to take a long-term view, that the market will develop. That’s why I’m an advocate for Photo London.

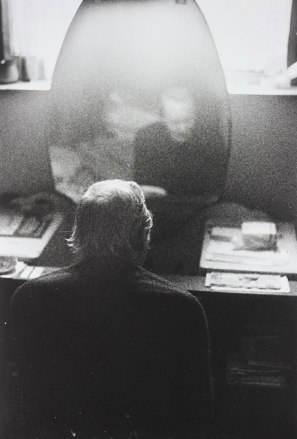

Royal Wedding – King George VI with the bride, Princess Elizabeth, 1947, (c) Bert Hardy, courtesy of the Hyman Collection

You have a particular interest in documentary photography. There’s always been the question of whether photography is art, and I think where that lingers most is in the area of documentary. How do you see documentary photography fitting in to the canon?

I’m interested in photography across the board, but the collection does include forms of documentary photography, especially subjective or conceptual practice. I’m not too obsessed with categories but I think it can be a question of intention. We have a photographer on Britishphotography.org, Nick Hedges, who did a fantastic project for the homeless charity Shelter, and it’s great work, but it has a didactic purpose. That makes me a bit uncomfortable because it separates it from most of the other work on the site. Generally, though, I don’t make the distinction because most photographers in the history of photography were documentarians, and many were commissioned by a third party. I think some of the judgment is to do with the status a photographer attains. Cartier-Bresson’s work is street photography and photojournalism, but because people love him, he’s considered an artist.

Still, conceptual photography is generally an easier sell in the art world. So do you think the answer is to integrate photography and art into combined fairs, or should photography have more specialized fairs like Photo London?

I think there’s room for both, but it’s an interesting question. As far as contemporary art is concerned, photography is already embedded, though dealers would probably refer to “artists working with photography” rather than “photographers,” to try to make them sound grander. At the artfair in Basel, Switzerland, they put all the photography dealers in a photography ghetto on one floor, and I’m not sure that’s a good idea because it means you’ve just got a whole section you can ignore. We dealers would like to reach people who aren’t specifically photography collectors but who are collectors or art lovers, and have them cross over. Because if you’re collecting 1920s and 30s French Modernism, and you’ve got your Picasso, your Max Ernst and André Masson, why would you not have Man Ray or Brassai as well? That’s our challenge, I think: to get people to look at the whole world of art more holistically. For my part, I’m not exclusively interested in photography, let alone British photography, it’s just that I can’t understand why such great work isn’t more appreciated. I’m doing what I can. But I’m just one voice among many.

———————————————————-

Visit Britishphotography.org here .

4 comments on “ Boost of British: An Interview with James Hyman ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Happy to have been of service. Very interesting, as usual. I wish I could have gone to the PHOTO exhibition. I bet James Hyman was very pleased with your post. Vera Coleman

Thank you Superfan!

Wonderful post. Thank you for pointing the way to a fantastic online resource/gallery.

You’re welcome, Stephen!