Home and Away: An Interview with Ed Kashi

Last week, renowned photojournalist Ed Kashi took over the Instagram feed of the photography nonprofit Cause Beautiful . He posted images and text from his 2012 book Photojournalisms , which had passed under my radar when it was published. When I saw the feed, then the book, I knew I needed to interview Kashi. His book was frank and moving, and it mixed text and image in a way I hadn’t seen before.

Like other photojournalists, Kashi typically spends at least six months a year on the road. He’s passionate about using photography as a vehicle for change, and has witnessed suffering and injustice in such far-flung places as Iraq, Nicaragua, Syria and the Niger Delta. It’s a lifestyle that doesn’t make for easy braiding with marriage and a family. As Kashi’s wife Julie Winokur writes in an essay in the book, “Most photojournalists are either single, or without children. The rest are in varying stages of divorce.” Yet Kashi and Winokur have beaten the odds, staying married for over two decades and bringing up two children.

Photography runs in the family: Kashi’s wife Julie Winokur and his children Eli and Isabel. Photo (c) Ed Kashi/VII Photo

In Photojournalisms , Kashi opens a door onto this challenging existence. The book mingles his images with journal entries and emails written to Julie, in which he recounts his experiences while striving to connect with her over time and space. “I just want to be close to you and the kids,” he writes, and “I love you so dearly and deeply.” But the reality of being home doesn’t always match the dream. “How distracted everyone is,” he notes on one return, “whether from your work or the digital gadgets and friends of the kids. And of course, you all must live your own lives, and so, you are not in sync with my rhythms and moods.”

Conversely, in Julie’s essay we get a sense of how it feels to be the one left behind. She confesses her ambivalent feelings toward the journal entries. They were “gnawing reminders of the rich life he was living all these years, while I was desperately trying to catch my breath, raising two children while building my own career,” she writes. “As he waxed poetic about the world, I felt like I was drowning.”

The words raw and intimate can be overused, but Photojournalisms earns them. Adding texture to his images, Kashi writes about the diverse events he has witnessed, from a suicide bombing in Lahore to an oil spill in Nigeria to a moving Romanian funeral. Like Winokur, he lays his emotions bare, and in doing so, gives us unique insight into a life of intensity, idealism and sacrifice.

I want to ask you about the book, but first—you just finished covering the visit of Pope Francis to New York City. What were your impressions of this new and revolutionary pope? What was the most moving thing you witnessed during his visit?

He seems extraordinary, certainly the most progressive pope in my lifetime. He speaks from the heart, for great values and political purpose beyond religion. Probably the most moving moment was watching a South Asian Muslim couple in Harlem excitedly pulling out their cellphones and reaching above the crowd to catch a shot of the Pope’s Fiat going down Lexington Ave. It was wonderful to see people from other faiths and cultures so excited to glimpse him.

“I broke down in the church, thinking of how beautifully this man’s death was being witnessed,” Kashi wrote of a Romanian funeral in 2001. Photo (c) Ed Kashi/VII Photo

So, the book. You started writing journal entries addressed to your wife and muse, Julie Winokur, soon after meeting her in 1992, eight years before you switched to daily emails. I assume the journaling was because sending letters was impractical, but did you ever send letters or postcards too? And how did it help you to address your journal entries to Julie?

I rarely sent postcards and never letters. I always needed the immediacy of writing to her at the moment and place I was, to feel connected. I had started this practice during my first marriage, which was short and very difficult, and then with a girlfriend before I met Julie, so it was an established part of me being away more than half the year and wanting to be connected to my mate, but obviously with Julie it took on far greater and deeper dimensions.

“The spill was disgusting…Shell should be ashamed of its behavior in Nigeria,” Kashi wrote in 2004. Photo (c) Ed Kashi/VII Photo

In your introduction, you talk about how electronic communication has given us “immediate intimacy…maintaining a strong sense of connection in the face of extreme distances,” but you also wonder if something has been lost amid the instant gratification. I was reminded of when my boyfriend-now-husband went to China in 1989 for six weeks and there was no communication. I hid six letters in his suitcase, one for each week, and when a letter arrived from him it was a major event.

You are way more romantic than me! What you did was wonderfully thoughtful and creative. At this point we’re so entrenched in our new connected world that it’s hard to imagine or even feel what it was like to have to wait for the gratification. We’ve certainly lost our ability to be emotionally patient and psychologically alone, or at least I believe I have. I stay in nearly daily contact with my wife and kids, at least via texting, and also often via emails. I can’t pass judgment on whether it’s good or bad; it just is. I can tell you that no matter how often I connect with my wife and kids, it’s still electric! But there’s no doubt we’ve lost some of the magic of making those special, rare connections that you have to wait for.

“I’m not yet worried, but it could escalate if they become aggressive,” Kashi wrote of his detention in Nigeria in 2006. Photo (c) Ed Kashi/VII Photo

Julie contributes a very frank essay at the end of the book, where she talks about her ambivalent feelings about the journals. Did she read the journals when you came home, and did you sense the ambivalence from her at the time? If so, was it disappointing that she wasn’t more enthusiastic about these documents you’d poured your heart into, or did you understand her ambivalence?

She often didn’t read the journals or would put them aside until she had the time to read them. I’m not sure if that was because of her mentality, which is Zen and patient, or her anger and resentment. But I would get upset when she seemed indifferent or too busy to read them and respond in an emotional way. I can see now how hard it was for her, and that my expectation was selfish and not realistic. She’s had to deal with a lot of resentment towards me and thankfully we’ve been navigating that, and are still. It’s not easy. I respect her for feeling the way she does. Frankly, what I do would never be tolerated by most mates. Julie is extraordinary: during this time she also worked full-time as a filmmaker and producer, raised two amazing kids as a half-time single parent, and has somehow continued to love me unconditionally. Are there times where I expect her to kill me? Why yes! Thankfully she is a woman of peace!

“I’m so thrilled and relieved to see you and Isabel getting on so well,” Kashi wrote from Taipei in 2010. Photo (c) Ed Kashi/VII Photo

You use your journals/emails to process some difficult emotions: being disgusted at the corruption of governments (both foreign and U.S.) for their atrocities, being frustrated when a story doesn’t seem to be coming together, being terrified when you were detained in the Niger Delta. How did the act of writing help you in those situations? Did you ever discover things on the page that hadn’t been apparent through the lens?

I used these journals as a way to stay alive, unconsciously feeling that the act of writing and being connected to Julie was almost like a proclamation that I was not alone, that I was safe, that someone was listening and that this was not all just folly. Quite often when I was writing I would be exhausted and unable to process most of what I’d observed, felt and thought about the day. I also often felt I was being indulgent, complaining about my loneliness and frankly being boring as a diarist. But the times I would be moved to write beyond my narcissism–due to a combination of clarity of mind, being energized and therefore being outside of myself—magic would sometimes occur. One entry that sticks out, and to this day makes me emotional, where the words were beyond anything in the accompanying image, was from Lahore, Pakistan in 2009. It was from the suicide bombing on my last night. I was trembling with emotion, anger and adrenaline. My images could never match the feelings I had at that moment.

“I kept on working, trying to find an angle that made sense of the chaos,” Kashi wrote of the aftermath of a suicide bombing in Lahore, Pakistan in 2009. Photo (c) Ed Kashi/VII Photo

When you were detained by the military in the Niger Delta (which I interviewed you about years ago for Photo District News), did writing your journal help you keep sane? Were you also writing it in order to have a full account of how you’d been mistreated? Did the guards know you were writing it?

The guards didn’t know or seem to care. I had to write some of it after my detention ended, as they confiscated my notebook for the last two days, when the SSS took us from the military. I was writing it as a form of defiance and validation of my life. Not to sound too dramatic, but it was essential for me to capture my feelings. Look, I’m basically a storyteller and constantly feel the need to capture life and define it for not only myself but for others. It’s this innate impulse that seems to drive me. During my detention, being able to capture my thoughts, feelings, observations, was a way to stay focused on what I needed to do, as a way to stay alive. I record, therefore I am.

How does the act of writing compare for you with photographing? Are there similar frustrations and joys, or is it a whole different ball of wax?

Writing can be nerve-wracking. You start with a blank page. With photography, it’s more a matter of deciphering how to manage the information that exists. They are completely different acts. What I love about writing, and I hope to do more of it as time goes on, is the ability to get to the core of an idea, or an emotion, or a fact, and convey that without ambiguity. Photography is all about being ambiguous, which is the inherent power of that medium.

Closer to home: Kashi photographed a deathbed scene in West Virginia as part of his 2003 book Aging in America . Photo (c) Ed Kashi/VII Photo

Throughout the book, I sensed how much you missed Julie but also, really palpably, how much you missed your two children and moments of their growing up. You say in the acknowledgments that “I hope one day my children, Eli and Isabel, will read this and gain a deeper insight into what their itinerant father had done while away from them for half their lives and how much I love and cherish them.” Have they read it yet, and if so, what were their reactions?

I think they’ve read it. I have a wonderful relationship with my kids. We’re truly blessed in that we know we love one another, respect each other, yet they don’t seem to care about what I do. If I was Jay Z, it would be a different matter! So I’ve learned to accept that for now they might have read the copies of the books I gave them with all my heart, but that I can’t expect them to make me feel the way I want.

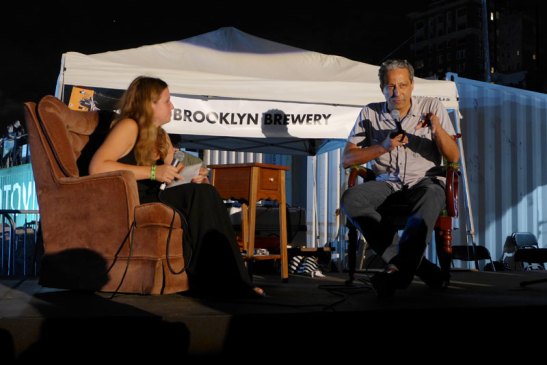

Kashi (right) in conversation with fellow photojournalist Katie Orlinsky at Photoville 2015. Photo (c) Sarah Coleman

On a related note, did you see The Salt of the Earth , where Sebastiao Salgado’s son talks about growing up with a largely absent father? He seems a little sad about it, yet deeply respectful and proud of his father’s work–and he ended up making a film about him! What are your kids doing now; has either of them inherited the creative gene?

I haven’t seen the film and know I must. I’m going through an extraordinarily busy and productive period, shooting films, stills, being president of VII Photo, on boards, teaching and lecturing, so I find I’m doing much less watching of other people’s work. This is not good but it’s the way things are right now. My kids are doing great. My son is a junior at George Washington University, on scholarships for baseball and engineering. My daughter is a senior in high school and is preparing to apply to colleges. She sometimes shows hints of creative impulses, but for now she wants to study psychology and help veterans with PTSD.

Speaking of psychology, I happened to be in the audience at Photoville last weekend when you appeared as part of an evening presentation by National Geographic . Each NatGeo photographer was asked what career they would have chosen if photography hadn’t been an option, and you said you’d have wanted to be a writer or a psychologist. What kind of writing would you have wanted to do, and why a psychologist?

I would have wanted to be a novelist, in my dreams, where I would spend long periods of time immersed in a story, and move from one project to the next. I had no idea what I was thinking of course. It was a fantasy. In some ways it’s come true, albeit in a form I never could have imagined. I remember when I was a teenager and Coke had its “I want to make the world a better place” series of TV ads. One of them showed a black kid with a young black man talking to him on an urban basketball court, kind of like a big brother scene. When I saw that it touched me deeply: I thought I’d love to be that older young man helping that kid. The impulse to engage, care, help and make things better has always been inside of me.

4 comments on “ Home and Away: An Interview with Ed Kashi ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

What an interesting man – very moving article – well written and evocative. Thank you Literate Lens

A great interview, Sarah. I felt I was talking to Kashi myself.

I agree with Michael, I wish English journalists would report their interviews using that transparent Q&A style. You make it seem easy, like a transcript, but it isn’t: in fact the (inferior) ‘essay with selective quotes’ style is lazier and more boring. On the subject matter, there is no need to impressed/in-awe of Kashi’s “six months a year on the road”. Many of us spend a good proportion of our nights away from home. Nobody cares about us, and we shouldn’t feel sorry for him — he is just doing his job. That said, he seems to do it rather well.

Thanks, Graham. As a journalist, I find it helpful to have both the essay and the Q&A option available. I think an essay can work better in some situations: for example, when there’s a lot of extra information to convey or when the interviewee isn’t eloquent (this is occasionally the case with photographers, who after all shouldn’t be expected to be gifted both verbally and visually). In that case, I can write around their thin quotes. But luckily for me, there are photographers like Ed who are extremely thoughtful and articulate, and then it’s a pleasure to do an unfiltered Q&A.

Also, your point about many people traveling for business is well-taken.