Fall Gallery Hop… and a Robert Frank Movie

Hard as it is to say goodbye to summer (even the sweaty, trash-scented New York kind), there are rewards to be had from fall. It’s the time when summer blockbusters give way to Oscar-contending movies, when publishers release books by heavyweight authors—and, in the same “back to school” mode, when galleries put on serious and noteworthy shows.

On a recent trip to Chelsea, I saw three very diverse, but equally interesting, photography shows. From a charming look at the history of self-portraits to a contrasting duo of street photographers to a deeply affecting meditation on abduction and absence, these exhibits showed how photography can cover a wide array of subjects and an even wider emotional range.

ME: Photographic Self-Portraits at Ricco Maresca aims to give a historical context for our current culture of selfies, showing that artists and regular folks have always delighted into turning the lens on themselves. The show opens with a wall of Photomatics (metal-framed portraits from the earliest photo booths) and closes with the work of “emerging artist” Kaia Miller, a twelve-year-old who uses her iPhone and various apps to make symbol-laden self-portraits. In between, there are works by such venerable artists as Imogen Cunningham, André Kertész and Berenice Abbott.

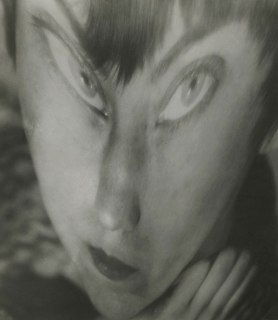

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that photographic history is littered with self-portraits: the self is a subject that is readily available and infinitely malleable. Within that availability, of course, there’s a choice of what to conceal and what to reveal. Perhaps unsurprisingly, only a few artists opt for warts-and-all depictions such as Pierre Dubreil’s 1932 close-up of eyes in a deeply wrinkled face, or John Coplan’s hairy 1999 Interlocking Fingers . Others romanticize themselves (as in Edward Steichen’s blurry 1900 self-portrait), use humor (Rosalind Solomon’s 1987 Self-portrait with Curtain ), or re-imagine themselves as something vaguely grotesque (Berenice Abbott’s distorted 1930 Self Portrait ).

The variety of these approaches, and their artistry, is a dispiriting contrast to today’s ubiquitous and unimaginative selfies. Perhaps in an effort to show that creative self-portraiture is still alive, Ricco Maresca has included the work of emerging contemporary artists Sara Salaway and Kaia Miller—which is a nice idea, and I wish I’d been more convinced by either body of work. Unfortunately, Salaway’s salt prints of an Anne Frank-ish face on cotton gauze seemed repetitive and uninteresting, and while at twelve Miller must be commended for her output, only some of her images were transcendent; others had the cloying sentimentality of an inspirational greeting card. Perhaps these deficits wouldn’t have stood out so much if the work hadn’t been hanging next to such masters as Kertész and Abbott.

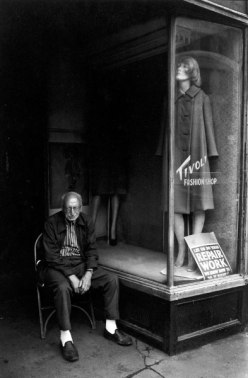

No such problems afflicted Long Stories Short , a retrospective of sorts at the Steven Kasher Gallery for the great, overlooked documentary photographer Jill Freedman. For many decades, Freedman has toiled in the documentary trenches, producing remarkable work—but although her best images combine the artistry of Mary Ellen Mark with the wit of Elliot Erwitt, she has not received the same recognition as either of those peers.

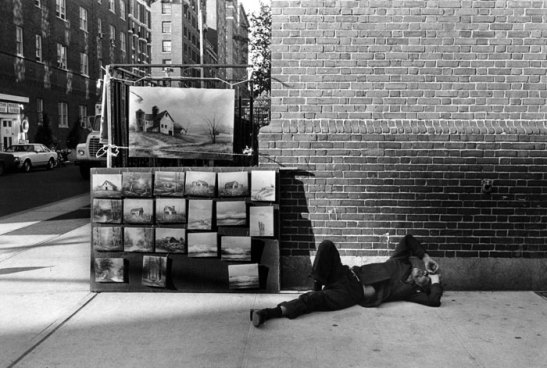

If there’s any justice, Long Stories Short should start redressing that imbalance. Freedman has an eye for the absurd, the tragic and the plain-out weird—and as the show’s title implies, each of her images compresses a whole story into a frame. Take Naked City , in which an elderly naked man pushes his way through a revolving door, or Surf’n Turf , in which a derelict sleeps on the sidewalk next to a display of painted ocean scenes. Full of both pathos and delight, these images made me laugh, cringe and wonder. With their sensitivity to the complexity of human stories, they impressed me much more than the more mundane blown-up street photographs by Leo Rubinfien in the gallery’s larger space.

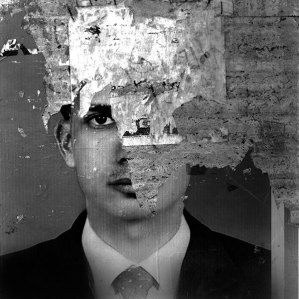

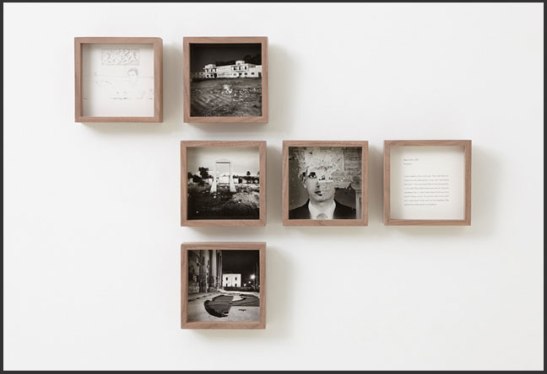

Likewise, at Rick Wester Fine Art I was drawn past Yona Monakhov Stockton’s candy-colored images of birds into the smaller back gallery, where a quieter show by Diana Matar was displayed. Called Evidence , the show had at its center a howling absence: that of Matar’s father-in-law Jaballa Matar, a Libyan dissident who was abducted during Muammar Gaddafi’s regime and never seen by his family again.

Photo exhibitions focusing on political issues run the risk of being worthy but dull. I went to this one with low expectations, but was quickly won over. The images were poignant, lyrical and unexpectedly moving, focusing on details—a bowl of eggs, an empty chair dappled with sunlight—that spoke of a life abandoned. The show also featured a highly effective combination of image and text, with Matar’s written reflections framed and hung as part of the installation. She traces the Libyan revolution and the death of Gaddafi (“I can’t quite believe what we are hearing,”) but also pauses to reflect on her father-in-law’s character: “I imagine men pausing in conversation, waiting for you to speak, and your wife wanting to make things graceful for you; your shirts ironed, your salads well seasoned, your papers dusted but left undisturbed.”

Evidence is also a book, which, like the exhibition, is intimate and soulful. While history books may teach us more facts about Libya under Gaddafi, Matar’s lyrical work captures emotion-states that are not so easily accessible. We feel her grief and anger, and share her desire to make sense of chaos and find meaning in what has been left behind.

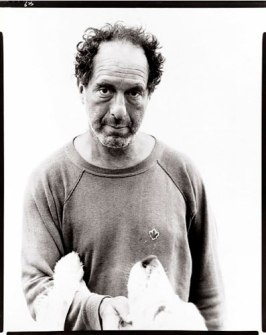

Finally, last weekend saw the world premiere of the documentary Don’t Blink: Robert Frank at the New York Film Festival. It was a hot ticket, and I was lucky to score a seat for the screening, which was attended by the 90-year-old Frank and included a post-movie Q&A with director Lauren Israel.

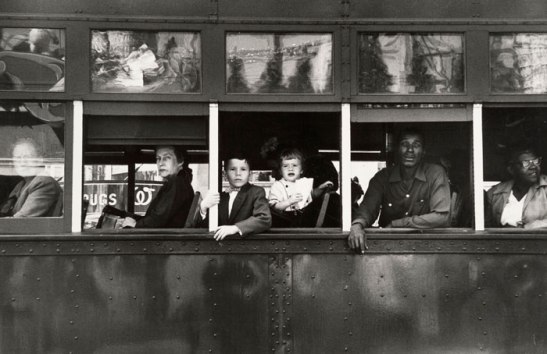

In 1959, Frank’s book The Americans put forward an unsettling view of a country that saw itself as unassailable. Looking beyond the picture-perfect suburban lawns and Tupperware parties, Frank saw segregation, political corruption and anti-Communist paranoia. He saw dead-eyed factory workers, harried urbanites, lonely night shift waitresses—and he captured it all, using an radical aesthetic of tilted angles, shadows and blur.

In subsequent work, Frank shifted to film, using his Beat Generation friends to play versions of themselves in aggressively non-narrative meditations on life and art. Misfits, truth-seekers and “people who live at the edge” interested him. In 1972 he made Cocksucker Blues , a documentary about the Rolling Stones that Mick Jagger subsequently banned. (“It’s a fucking good film, Robert, but if it shows in America we’ll never be allowed in the country again,” he apparently said.) Now, at 90, Frank still patrols the streets of New York on the lookout for interesting characters.

An unconventional man needs a quirky documentary, and that’s what Israel has delivered. Rather than progressing chronologically through Frank’s life, Don’t Blink offers a lively collage of images, interviews and clips of his experimental films, moving back and forth through time and using atmospheric music to give a sense of decade and place (the Velvet Underground, naturally, signals 1970s New York).

What emerges is a portrait of a man who observes the world with sharpness and wit, who compulsively collects odds and ends, and who is almost pathologically direct (we see him torturing a reporter whose questions he deems “irrelevant”). He can be famously cranky, but also funny and blazingly honest. “The main thing is to get it over quick,” he says of photography. “When someone becomes aware of the camera, it becomes a different picture.”

With The Americans , Frank produced a body of work that expanded the possibilities and emotional range of photography. His influence is enduring, and it pervades some of the work in the exhibitions above. They show what a versatile, eloquent medium photography has been—and what it can continue to be, even in the age of iPhones and selfie sticks.

——————————————————–

ME: Photographic Self-Portraits is at Ricco Maresca Gallery until October 31. For more details and opening times, click here .

Jill Freedman: Long Stories Short is at Steven Kasher Gallery until October 24. For more details and opening times, click >here .

Evidence by Diana Matar is at Rick Wester Fine Art until October 24. For more details and opening times, click here .

There are no release dates for Don’t Blink: Robert Frank . For information, check periodically here .

17 comments on “ Fall Gallery Hop… and a Robert Frank Movie ”

Information

This entry was posted on October 12, 2015 by sarahjcoleman in Art Photography , Events , Exhibitions , Films and tagged Berenice Abbott , Diana Matar , Don't Blink: Robert Frank , Evidence , Gerald Slota , Jill Freedman , Lauren Israel , Long Stories Short , ME: Photographic Self-Portraits , Ricco Maresca , Robert Frank , Steven Kasher , The Americans .Shortlink

https://wp.me/p25Qfq-3b1Recent Posts

Archives

Categories

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Join 11,055 other followers

I miss New York so much! I grew up there, but moved to L.A. from NYC four years ago. There’s definitely an art scene here, but reading your post really made me miss what NYC has to offer! 🙂

Thanks for this nice comment, Teresa! I’m glad I could give you a little taste of NYC!

This is a wonderful piece, especially the writing about Evidence, which made me want to see it in person. You have a way of describing photography that brings out its character, which is a difficult task in writing. I found the inclusion of the Robert Frank movie a bit discordant and would have liked to read about it in greater detail on its own, but I did think it contributed atmospherically to this piece.

Thank you for writing it.

Gosh, I love Robert Frank. He told such an important story at a pivotal time. I’m curious — what stories are essential today? There is still racism, economic injustice, and inequality. Are news photographers, rather than art photographers, more important because Frank’s themes are now understood to be part of the fabric of human (especially American) life?

Hi JodiLC, thanks for your comment! I think you raise a really interesting question. Certainly there are still a lot of essential stories, and photographers telling them; the problem (especially with the slow death of traditional media) is finding them in the thicket of Instagram and Twitter and the blogosphere. The whole question of photojournalism vs. art photography is fascinating too. When is an image ‘art’ as opposed to ‘documentary’? It’s not always clear. Some photographers straddle the divide, while others prefer to stay firmly on one side.

A friend of mine, Larry C. Price, is doing amazing work on child labor in the developing world ( http://larrycprice.com ), and another friend, Stephanie Sinclair, has been working on the issue of child marriage for a decade and has launched a nonprofit ( http://tooyoungtowed.org ). Many talented photojournalists, including Lynsey Addario, have been working on the migration issue in Europe. As far as issues in the U.S. go, I can’t immediately think of anyone who’s attempting as ambitious a country-wide survey as Frank did, but Magnum photographer David Alan Harvey does road trips around the country, and I’d recommend Peter van Agtmael’s book ‘Disco Night Sept. 11,’ which contrasted the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan with U.S. perceptions about them ( https://theliteratelens.com/2014/05/12/dancing-while-rome-burns/ ).

I am learning so much reading your articles Literate Lens – as a UK resident I really miss all this good stuff – although London has a lot to offer to be fair! Robert Frank comes across as a very unique man – very inspired and inspiring as well as challenging. Broad and interesting social commentary of the time. Many thanks

Another very interesting blog, Sarah. I wish I had been able to see ‘ME:Photographic Self Portraits’ and will try to get ‘The Americans’ from the library.

As always, you offer such fascinating and pointed commentary. I always want to rush out to follow your lead, and the experience is always enhanced by your analysis.

I loved the variety of the three shows you covered here and the different perspectives covered. That Berenice Abbott self-portrait is quite haunting. I’ve never seen it before. Always learning with you!

Oooh, I want to see the Robert Frank film.

Perhaps The Americans tells us as much about Robert Frank as about the essence of America, given that Frank purportedly shot many thousands of negatives for the project before curating them into a book of a few dozen ideologically consistent images. What other, possibly contrarian, views might be lurking among those unknown negatives?

joekashi: I agree absolutely. The edit of The Americans is really interesting. Frank included some images that I don’t think are particularly strong aesthetically, but that obviously contributed to the story he wanted to tell. It would be fascinating to see what ended up on the cutting room floor.

Reblogged this on gguyphotography and commented:

A piece on one of my favourite photographers, will check it out and review very soon!

Thank you!

i love NYC – visited it umpteen times and each time i leave, i leave a little bit more of myself. i feel homesick for this wondrous place. this piece really made me feel nostalgic for the ‘old NYC’ – a time and place i can never visit, or even revisit – except through wonderful exhibitions such as those described.

as a writer, professional photographer and now aspiring film-maker, i found this piece really interesting.

and Sarah, i love this site – so much to offer and share with people like myself. thank you for this. ’tis, like NYC itself, a wondrous place to be…

Thank you, Katm! Do you have a website I can look up?

i hope you enjoy what you see/read/hear… thank you for your interest, Sarah. it is greatly appreciated 🙂