Responding to August Sander… in Poetry

Stalwart, pensive, anonymous: the people in August Sander’s portraits are identified only by their jobs or social classes. A bricklayer; young farmers; a professional middle-class couple. Look past the titles, though, and the subjects of these images defy any attempt at collectivism. Through nuances of gaze and gesture, they display a powerful individuality. Nothing is simple , their expressions say. People least of all .

Born to German working-class parents in 1876, Sander lived to see the social upheaval of the 1960s. His life’s work, a compendium of portraits titled People of the Twentieth Century , was nothing if not ambitious. He wanted to document German society from top to bottom, and the project would consume him for over three decades. Even after his first book was banned by the Nazis—who thought his subjects insufficiently Aryan—he doggedly continued the work.

I’ve interviewed a lot of portrait photographers over the years, and many have cited Sander as a primary inspiration. He’s one of a few photographers—Arbus, Avedon and Salgado are others—whose work is revered to such an extent that they’ve become almost holy, the Prousts and Dylans of the photo world. Now, Sander has provided inspiration for Adam Kirsch, a writer who has used these portraits as jumping-off points for poems exploring class, gender and politics.

Initially, I was skeptical about Kirsch’s book, Emblems of the Passing World , just out from Other Press . On their own, Sander’s images embody something so close to perfection that it seems heretical—or at least dangerous—to mess with them. Also, embarrassing as this is for a writer to admit, I’m not a huge poetry fan. For every poem I’ve experienced as transcendent, there are many more I’ve found impenetrable, overheated or ludicrously precious.

But by the third poem in Emblems , Kirsch had won me over. Like Sander, he gives us work that is quiet, clear and well made. But like the portraits, Kirsch’s poems are also complex and rewarding of our study. They focus on nuances of gesture and expression, using them to examine how class, gender and looks affect a person’s status and destiny.

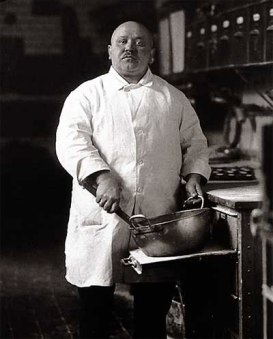

For the poor, that destiny is pretty miserable. A group of working class country children might look happy enough, but their shaven heads and wide-set eyes suggest “that they’ve been fed/A vitaminless food/And made to stay inside/Until whatever should/Have made them golden died.” Equally neglected, a young match-seller “must play at the charade/Of taking part in the economy,” but is really there to reassure the rich that he “won’t get angry or vote Communist/As long as someone comes to buy a match.”

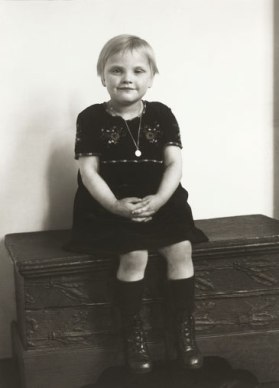

If poverty is a bitch, though, middle-class life has its complications too. In Middle-class Child , a girl’s clasped hands and smile show confidence that she “won’t need to hit or grab/To get the good things life has promised her.” But is it good that her life has been arranged to “put off the discovery of loss”? Or will it just make that loss harder to bear when—inevitably—it comes?

Occasionally, something comes along to shake up the social order and disrupt expectations of class and gender. In the 1929 portrait Fitter , we see a mechanic in overalls, in whom beauty has been planted “like a bomb or mine”, making him a “natural aristocrat”, who’s “winning in the one arena where/The game’s not rigged in favor of the rich.” Conversely, in Professional Middle-class Couple , a mild-looking man and wife demonstrate that “the faces money makes…don’t have to be obtuse,/Entitled, vapid, arrogantly strong”. These things upend our expectations, and at least in the second case, Kirsch hints, offer hope for a more compassionate world.

By contrast, people who try to be the most transgressive might be fooling themselves. A bohemian painter’s wife who wears trousers and short hair in 1926 is a “suitably inventive mate” for the invisible painter, Kirsch notes—but this doesn’t make her equal. With dry humor, he points out that “it’s safe to say that [the painter]/Does not feel that he has to wear/A skirt or ribbons in his hair”.

I laughed out loud at that—a rare moment of levity in a collection that, for the most part, has an air of mournfulness and anxiety. Kirsch’s reflections come very much from the present, informed by what we know about German history and the events that unraveled in the 1930s and 40s. In 1925, a fraternity student with facial scars is prepared for a future of “keeping quiet, following commands/Stopping at nothing, knowing how to bleed.” In 1943, a pretty young woman’s military blouse hints at how “her generation has in store/a fate less lovely and more serious.”

In less sure hands, poems like these could have seemed gimmicky or opportunistic, and—like a bad movie adaptation—could have cast a shadow on the source material. But Kirsch pulls off a difficult act: his poems artfully articulate inchoate feelings we might have had about these images, but also offer unexpected insights. Throughout, the book is filled with inventive, alive language: a newborn is perturbed to leave the “plush womb with its steady roar”; a young, blossoming girl has “biological celebrity.”

I guess some Sander purists might be offended, wanting to leave the photographs to speak for themselves. But to me, those objections would be missing the point. Unlike an academic treatise, Emblems of the Passing World doesn’t aspire to be definitive. Instead it’s a dialogue, a series of explorations that pays homage to one of the twentieth century’s great observers. Astute and thought-provoking, it made me appreciate Sander’s work more than ever.

——————————————————————————————————

19 comments on “ Responding to August Sander… in Poetry ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Very lucid commentary on his times and someone who was previously unknown to me – a moving and enlightening piece

Thanks, Joanna. August Sander’s work is fantastic and well worth checking out. He’s revered among photographers for good reason!

What a fascinating piece. The portraits you include are penetrating. I thought the ‘Middle Class Child’ was poignant, now we know what happened in Germany in the following 20 years, and the composition of the stance of the ‘Painter’s Wife’ was so right.

Agreed, Michael. I like the way Kirsch undercuts the feminist triumphalism of the painter’s wife; it made me think differently about the image. In a truly feminist world, SHE would be the painter!

Sarah, Thanks so much for introducing me to both Sander and Kirsch’s work. Like yourself, I’m not a huge fan of poetry, but I have a feeling that Kirsch’s Emblems of a Passing World might sway me a bit. Terrific post!

Thanks, rnewman504! These are smart and interesting poems — give them a whirl!

Here’s a link to one. Not my favorite in the collection, but will give you a taste: http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poem/239104

Sarah, I’m going to pick up Adam Kirsch’s book. I’m always on the hunt for new poets to read. I love your review, it’s very balanced and I feel like I was able to get an understanding of both the poetry and the photography, I also didn’t know Sander’s work and am going to check out his portraits. Thanks for the quick lesson on these folks.

You’re welcome, brooklynbabyal! Thanks for stopping by.

As a photographer who sites Sander as a major influence and a writer who also has difficulty with poetry, I am especially appreciative of this post. The Literate Lens is one of my favorite blogs. Keep up the excellent work!

Thanks, Amy. It doesn’t surprise me to learn that Sander is important to you!

Did I see these photos at a Metropolitan Museum exhibit several years ago? They look so familiar. At any rate, I think it’s always interesting to read poets, or writers of prose, reacting to other art forms, visual, musical, whatever. Someone thoughtful and articulate can only add to the original experience. Thanks for this, Sarah!

Thanks, Susan. You might well have seen them at the Met. I wish I had, although I did see a vintage print of the pastry chef at AIPAD (the annual photo dealers’ festival) last year. There are only a few prints of that image and it was selling for $1 million!

There once was a fine pastry cook

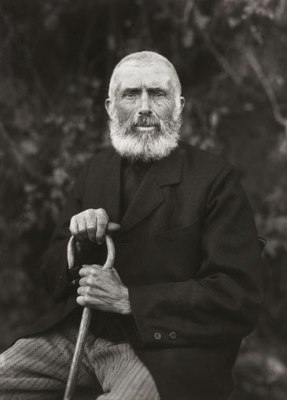

And a man of the soil with a crook

Several farmers impressed

With a child on a chest

Put their family snap in a book

Can I put in a request for an piece about Vik Muniz? I guess your articles are ‘event driven’. i.e. if Vik does not venture out of Brooklyn, he doesn’t get on the radar screen?

Seriously, we love the magazine (blog?) though. Whenever my art student son asks me about photography I just tell him to look here — it seems to work

Graham: Don’t give up your day job! Just kidding. Thank you for reminding me about Vik Muniz. I’ve always liked his work I’ve seen, but have never explored it in depth. Maybe it’s time to change that. I have been known to venture out of Manhattan at times (see posts on Photoville and Peter Funch), but Vik is a bit of a superstar and I’m not sure I could just pop in to his studio for a cuppa. May be worth a try though!

Such a thoughtful post, Sarah. I read it twice and it has since stuck with me suggesting that I need to seek out this book. ThanK you!

Thanks for introducing me to Sander and Kirsch, as usual, I learned a great deal from this blog. I minored in poetry in my undergraduate years, so I read this with great interest. I tend share the caution you write about in terms of putting poems and photographs together. I think photographs and poems oftentimes serve the same purpose, forming portraits of a particular person or scene at a distinct moment in time. But this piece opened my mind to the idea of that added dimension that can result from such a “collaboration.”

Great post! I’m curious, does Kirsch explain his fascination with Sander? Maybe in the book’s preface or an interview?

Great idea for some new reading material… loved it.