Turning the Tables: An Interview with Sarah Coleman

Earlier this year, I was interviewed by

Mark Jenkinson

for his book

Photography Careers: Finding Your True Path

, which is coming out soon from

Focal Press

(just in time for you to buy it for the holidays). Given that I’m usually the one asking the questions, it was a unique and fun experience to be interviewed by Mark. His depth of knowledge about photography led to some great questions, and, at the risk of being narcissistic, I thought it I would run some excerpts from the interview here.

Earlier this year, I was interviewed by

Mark Jenkinson

for his book

Photography Careers: Finding Your True Path

, which is coming out soon from

Focal Press

(just in time for you to buy it for the holidays). Given that I’m usually the one asking the questions, it was a unique and fun experience to be interviewed by Mark. His depth of knowledge about photography led to some great questions, and, at the risk of being narcissistic, I thought it I would run some excerpts from the interview here.

In Photography Careers , Mark casts a wide net, going beyond the typical career advice book. As he points out in his introduction, the landscape of photography has changed immensely in the last few decades. But while “the digital revolution has created a host of new creative options and career opportunities,” jobs in photography are becoming increasingly individual and idiosyncratic, meaning that “the most resourceful, inventive, and adaptable” people usually fare best.

That’s why, in addition to interviewing professional photographers for his book, Mark (who has been a professional photographer and teacher of photography at NYU for 25 years) also talked to people in the fields of curating, photo retouching, stock photography, photo editing, art therapy and writing (that would be me). Increasingly, the boundaries between these fields are becoming more porous, and people entering the business today might find themselves making careers that span two or more areas.

In the book, each interviewee gives a full rundown of how he or she got involved in the field, then describes its rewards and drawbacks. As Mark concludes in his introduction, the softening of boundaries in the photography world “[is] actually the best part because you will be forced to build a career that is uniquely your own.” I couldn’t agree more.

Mark Jenkinson: I know a lot of people who write about photography, but most also teach or curate. You are a writer first and foremost, and you have chosen photography, almost exclusively, as the subject you write about. Your career is also interesting because you write about it from so many perspectives: fiction, art reviews, and actual reportage on the industry. Of all things, how did you end up writing about photography?

Sarah Coleman: I grew up in England, where there’s no such thing as a liberal arts degree, and I was always equally interested in writing and visual art. It was a big conundrum for me because when you go to college there you have to choose one thing to study, and I found it very difficult to decide. So what I did was go back and forth for a while. I did a one-year pre-degree art course, then I was an English major at Cambridge, and then I went to the Slade School of Art in London for a degree in fine art printmaking. You know, two degrees wasn’t enough! So I came over to New York and did creative writing at Columbia. I was looking for a way to put it all together and I happened to be taking a class in black and white photography at the

International Center for Photography

with

Harvey Stein

. I told him that I was about to get married and move to San Francisco, and I wanted to write, and I wanted to do photography, but I really didn’t know how to go about this.

Sarah Coleman: I grew up in England, where there’s no such thing as a liberal arts degree, and I was always equally interested in writing and visual art. It was a big conundrum for me because when you go to college there you have to choose one thing to study, and I found it very difficult to decide. So what I did was go back and forth for a while. I did a one-year pre-degree art course, then I was an English major at Cambridge, and then I went to the Slade School of Art in London for a degree in fine art printmaking. You know, two degrees wasn’t enough! So I came over to New York and did creative writing at Columbia. I was looking for a way to put it all together and I happened to be taking a class in black and white photography at the

International Center for Photography

with

Harvey Stein

. I told him that I was about to get married and move to San Francisco, and I wanted to write, and I wanted to do photography, but I really didn’t know how to go about this.

He told me to go see his friend Jo Leggett, who owned a photography magazine there. She had bought this magazine called Photo Metro that started off as a free community thing. It was very beloved among San Francisco photographers. I ended up interning with her, writing about photography there, and it just kind of grew from that. I got a gig reviewing art with the San Francisco Bay Guardian and soon I was writing for almost all the local papers in the Bay Area.

Then I moved back to New York and initially I got a job with a non-profit magazine called

World Press Review

(which now only exists online) and I was doing that for a few years. Part of my position there involved doing some photo editing. After that, I got a contract position with

Photo District News

producing one of its corporate-sponsored publications,

VisionAge

(sponsored by Olympus). I did that for 5 years, in addition to writing for the main magazine. When

VisionAge

ended, I started writing a historical novel based on the life story of an actual photographer. I also launched

The Literate Lens

in 2012, and the blogging has been a really great thing because it’s led to some other opportunities.

Then I moved back to New York and initially I got a job with a non-profit magazine called

World Press Review

(which now only exists online) and I was doing that for a few years. Part of my position there involved doing some photo editing. After that, I got a contract position with

Photo District News

producing one of its corporate-sponsored publications,

VisionAge

(sponsored by Olympus). I did that for 5 years, in addition to writing for the main magazine. When

VisionAge

ended, I started writing a historical novel based on the life story of an actual photographer. I also launched

The Literate Lens

in 2012, and the blogging has been a really great thing because it’s led to some other opportunities.

MJ: But what is it specifically about photography, out of all the things one could write about, that was so interesting? Obviously it’s a great subject, but it’s also a pretty limited market.

SC: I think it came from the fact that I had been taking these classes in photography at ICP and I was in one of the last generations to have that amazing experience of learning black and white darkroom printing as the primary way of making a photographic image. I just loved black and white printing, it was something I could really understand and get my head around as a craft, whereas digital photography has been harder for me because I’m not very technically minded. I fell in love with the darkroom, and with black and white photography.

In a broader sense, though, to answer the question ‘Why photography?’ I would say that the medium is just so of-the moment–I think now more than ever, photography is infiltrating every area of our lives.

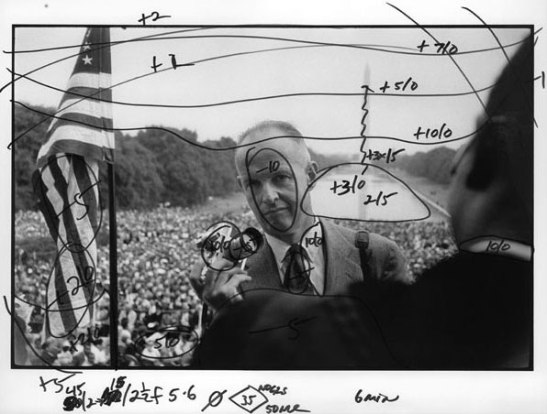

This shot of Henri Cartier-Bresson photographing Martin Luther King shows the darkroom notations of Magnum printer Pablo Inirio. It was featured in The Literate Lens’ most popular post, Magnum and the Dying Art of Darkroom Printing .

MJ: Exactly. Meanwhile people talk about photography as if it’s dead. I think it’s actually become so pervasive that we just don’t even notice anymore.

SC: That’s why I feel that it is important now to have smart writing about photography. It’s just everywhere, and we need to be able to look at it, analyze it, and figure out some of the nuances.

MJ: Like what? Can you be more specific?

SC: It’s difficult to talk about nuances without referring to specific photographs, but take for example Thomas Hoepker’s famous photograph of the people relaxing in Brooklyn on the waterfront while the Twin Towers are burning in the background. That’s a photograph that you can look at and at first read it as: “Oh these blasé New Yorkers know the world is collapsing and they’re just sitting there goofing off and having fun.” But then it came to light that there was a much more complex story behind it, and those people were having a serious discussion about what was going on… So I think we just have to be smart about things like that and aware of them, because images are very seductive, and it’s very easy to just be sold a story or version of events.

Thomas Hoepker’s image from 9/11 was discovered to be more nuanced than it at first appeared to be. Photo (c) Thomas Hoepker/Magnum Photos

MJ: You’re writing a novel about photography. Is your protagonist a photographer? Can you tell me a little bit about your novel?

SC: (Laughing) One of my three degrees was in creative writing, I have always wanted to write novels, and I’ve had some false starts. Then I went into journalism and got distracted for 15 years. When the recession hit in 2008 and my freelance work started disappearing, I thought it was time to sit down and write this novel. I’ve been a bit cagey about giving away the specifics, but I’m hopeful that by the time your book goes to press I’ll have a contract with a publisher, so I’ll tell you that it’s a historical novel based on the photographer Berenice Abbott. She had an amazing life, she was around for the birth of documentary photography and had very strong opinions about what photography should and shouldn’t be. It’s funny to look back on that now because I think we have such a big umbrella, we have room for everything in photography, but in the early twentieth century there was a fierce debate about what photography could and couldn’t be, and she was part of that.

MJ: Oh that’s great, she had a big life as photographer and she was also witness to a lot of the history. She was Man Ray’s assistant, and she discovered Eugene Atget.

SC: Exactly, nobody would know who Eugene Atget was had it not been for Berenice Abbott. There is a rich tradition of photographers rescuing other photographers, like the Vivian Maier story ..

MJ: You’re right. Now that I think of it there is a history of photographers rescuing the work of other photographers; Lee Friedlander rescued E.J. Bellocq, and Henry Darger ’s work was also discovered by a photographer, Nathan Lerner.

SC: And there’s the work of Mike Disfarmer that was rescued as well. I think that if you’re a creative person and you find someone’s work that you think is amazing and it’s not getting any recognition…. there are some people who would just walk away, but others who feel compelled to rescue the work.

So yes, Berenice Abbott rescued Eugène Atget, and to a lesser extent, Lewis Hine as well. I think she just felt it was unfair, she saw a lot of photographers whose work she thought was pretentious, like Steiglitz — she had a real animosity towards Steiglitz. And meanwhile she was encountering these other photographers who she thought were amazing and weren’t getting any recognition at all.

Vivian Maier, shown here in an undated self-portrait, is the latest in a line of photographers to be recognized posthumously

MJ: The thing I’ve liked about your writing, and the reason I asked to interview you is that you seem to actually like photographers.

SC: Well I’m glad that comes across! Perhaps having practiced photography a bit helps me appreciate photographers more. I think writing for PDN has probably shaped that appreciation as well because the magazine exists to serve photographers and the industry. I tend to gravitate more towards documentary photography and photojournalism because there are all the ethical issues around that work that are very interesting to consider. I am fascinated by people who choose to do that work and engage with those issues.

I think of myself as a humanitarian and I think a lot of photojournalists get into it for that reason as well. They are idealistic, humanitarian people who go and expose terrible problems all over the world, trying to get people engaged and create some change.

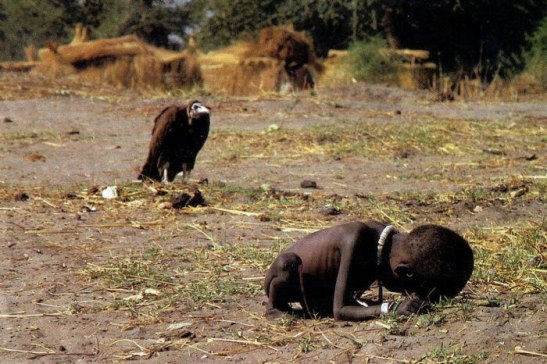

The problem is that once they get into the actual work it turns out to be more complicated most of the time. I’ve interviewed a lot of photojournalists over the years and there is the obvious problem of how you choose to help in a given situation. You can rationalize it all you want, and I mean it is a big question, “do I help this person to survive or do I get this picture in the New York Times?” It’s not a such a simple question because the photo might motivate people to donate money and change things on a bigger scale. I think it’s a really difficult dilemma a lot of the time and that’s one thing that weighs heavily on those guys. An extreme example would be Kevin Carter.

MJ: Sorry, I’m unfamiliar with him, what was the story?

SC: He was one of the members of the ‘Bang-Bang Club’ of photojournalists in South Africa. He won the Pulitzer Prize for his photo of a starving child in Africa with a vulture sitting near by. A couple years later he committed suicide, partly because he felt like everyone had been celebrating the photo but it hadn’t caused any significant change.

MJ: You’ve been writing for Art News most recently, what kind of things are you doing and how is that different from writing for PDN or your blog?

SC: I review shows for them that are in Chelsea galleries, downtown, Brooklyn. Usually there is a photographic component, but it is fine art photography. I think that gets back to the question of why photography for me, because however abstract and conceptual a fine art photograph becomes, it still has to be rooted in realism in some way. Art News is a good match for me compared to some of the other art magazines. There’s a kind of writing about art that is very high flown and intellectual, and I think it can be very obfuscating and verbose. I like plain speak. What I like about Art News is that they value that as well.

I do sometimes get annoyed by very theoretical work, because I think there can be a tendency among fine art photographers to speak to about five people in a city that’s populated by 8 million. But I also think it’s interesting to look at work like that and examine it in a different way and to ask why is this annoying me so much, and what’s the history behind it.

I do sometimes get annoyed by very theoretical work, because I think there can be a tendency among fine art photographers to speak to about five people in a city that’s populated by 8 million. But I also think it’s interesting to look at work like that and examine it in a different way and to ask why is this annoying me so much, and what’s the history behind it.

MJ: Is there a question that I haven’t asked that would give people a greater insight into what you do?

SC: I guess one thing that I might say is there can be a misperception about people who write critically about the arts. I think some people assume that the person would be doing that thing if they were good enough and just because they’re not good enough they are writing about it. But it’s actually pretty hard to be a critic: it takes discipline, curiosity and a lot of thinking and revising. I like practicing art, and I have done so in a number of ways in my life, but I think at my core I am a writer. The blog that I launched, I do that purely for pleasure. No one is asking me to do it, no one is paying me (unfortunately) but it has led to other things.

If I had to say one more thing it would be about money. I think people reading your book will probably know they are entering a profession where they are not likely to become rich very quickly, or ever. So you have to love what you do, enough to compensate for the paltry income. It’s difficult to make a living writing about photography; it helps if you can get a staff position or a regular column. In the last six years I’ve made a big gamble by writing a novel that I hope will get published and make some money. Fingers crossed! But obviously, I didn’t go into this field to rake in the big bucks.

(FYI, my interview in the book is much longer and, in the interest of space, I cut out some really good parts. So go buy the book! If you click on the cover image below and buy the book or anything else from Amazon within 24 hours, The Literate Lens will even get a small commission!)

——————————————————————————————————–

8 comments on “ Turning the Tables: An Interview with Sarah Coleman ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Thank you for your continued insights and inspirations Sarah! Your ideas/posts are a gift.

Thank you. This was absolutely fascinating and very enlightening.

Thank you for sharing your insight. Good luck with your book!!

Thanks for sharing this background. It’s fascinating. As always, I learned something new when I read The Literate Lens!

Very interesting. The “autobiography through the looking glass” technique is highlyeffective.

“I like plain speak.” Hear, hear! Can’t wait for the novel…

Lovely interview. So nice to hear from YOU, Sarah!

Yes thank you for sharing this! It’s not narcissistic at all. They were questions I would have liked to ask you!