A Lesbian Gun: Words and Images Inspire Todd Hayne’s New Masterpiece ‘Carol’

In writing and film, storytelling is often a dance between the narrative and the visual. Fiction writers use vivid descriptions to help readers visualize a story’s world, while a film’s visuals often emphasize its narrative themes.

In writing and film, storytelling is often a dance between the narrative and the visual. Fiction writers use vivid descriptions to help readers visualize a story’s world, while a film’s visuals often emphasize its narrative themes.

Few contemporary filmmakers are as visually minded as Todd Haynes , whose movies seamlessly blend stories and ideas with thoughtful, striking aesthetics. In Haynes’ new movie, Carol , a story of forbidden love unspools against a pitch-perfect evocation of 1950s New York. The film is shot in a beautifully muted palette with flashes of color, reminiscent of old Kodachrome prints. It’s ravishing, and it wasn’t a surprise, when I attended An Evening with Todd Haynes at the Film Society of Lincoln Center on Wednesday night, to learn that the works of photographer Saul Leiter were a big reference for Haynes when he made the movie.

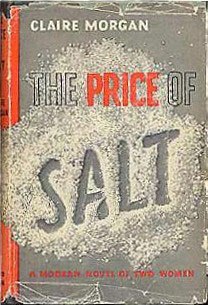

Before I get to that, though, a little more about the movie and its source material. Carol was adapted from The Price of Salt , Patricia Highsmith’s second novel, published in 1952. Its subject—two women falling in love—was incendiary for its time, and Highsmith , who had achieved some fame with her first novel, Strangers on a Train , initially published it under a pseudonym. It was publicized as “the novel of a love society forbids” and sold over a million copies.

Though

The Price of Salt

is told in the third person, the story is filtered through the mind of Therese Belivet, the more vulnerable and less experienced of the lovers. At nineteen, Therese is bursting to experience a world that she regards with a mixture of excitement and cynicism. She’s disillusioned with her holiday job in a department store, and unenthused with her adoring boyfriend. In other words, she’s ripe for a breakout when older, sophisticated Carol Aird comes into the store, looking for a Christmas present for her daughter.

Though

The Price of Salt

is told in the third person, the story is filtered through the mind of Therese Belivet, the more vulnerable and less experienced of the lovers. At nineteen, Therese is bursting to experience a world that she regards with a mixture of excitement and cynicism. She’s disillusioned with her holiday job in a department store, and unenthused with her adoring boyfriend. In other words, she’s ripe for a breakout when older, sophisticated Carol Aird comes into the store, looking for a Christmas present for her daughter.

Without doubt, one of the great gifts of novels is the way they take us deeply into a character’s thoughts and inner life. Movies, which observe characters from the outside, can’t offer that intimacy—that is, unless the director chooses to use voiceover, which rarely feels natural or organic. In adapting a movie from fiction, then, a director has to rely on externals, from music to visuals (chiefly the actors’ expressiveness and the cinematography) to do the heavy emotional lifting.

In Carol , Haynes summons Therese’s point of view through his aesthetic (created with cinematographer Ed Lachman ), which is at once softly delicate and precisely observed. Reminiscent of Leiter’s photographs, many scenes are shot through windows or gauzy curtains, giving them a hazy, dream-like quality. There’s a lot of snow (the movie takes place over five winter months), and a lot of scenes in diners: both are favorite tropes in Leiter’s work.

Leiter, who initially wanted to be an Abstract Expressionist painter, was an early adopter of color photography. Sometimes, to get a different effect, he allowed his Kodachrome film to expire before using it. The adjective I’ve seen most to describe his work is “painterly,” with “abstract” running a close second. Although there isn’t a huge amount of connective tissue between him and his contemporaries Robert Frank and Diane Arbus, each broke the mold in some way, and together they’ve been heralded as a photography movement, the New York School.

“My little look book, where I nerd out and collect imagery, is about the visuals of a movie,” Haynes said on Wednesday night. Leiter’s images inspired him for the way the photographer “is interested in what gets between him and his subjects.” When there’s something in between viewer and subject, “it reveals the predicament of looking, Haynes said, and also “stokes desire, because you want to get around [the obstacle].”

Certainly, desire is stoked—as one audience member pointed out, Cate Blanchett is “so carnal in this movie that I’ll bet that, for ninety minutes, straight women in the audience were gay.” For me, though, the more revelatory performance was by Rooney Mara, whose mixture of intelligence and fragility was breathtakingly complex. “It was not quite insanity, but it was certainly blissful,” Highsmith writes of Therese’s infatuation with the older woman. In the movie, riding in Carol’s car for the first time, Mara’s Therese looks out of the window and allows herself a tiny, amazed smile—a quiet flash of the joy burning inside.

An Evening with Todd Haynes was the first night of a Haynes retrospective at the Film Society of the Lincoln Center: the retrospective continues through November 29. (New Yorkers, take note: there’s still plenty of good stuff to see!) For the retrospective, Haynes has paired each of his films with a companion piece that in some way illuminates it. Carol was paired with Lovers and Lollipops , the second feature film by husband-wife team Morris Engel and Ruth Orkin , who were both successful still photographers before they turned to film. Together, Engel and Orkin pioneered a low-budget style of filmmaking that influenced the French New Wave, and Haynes said he was influenced by their film’s look and naturalism. (Earlier this year, I wrote about Orkin and Engel here .)

As Haynes pointed out, Orkin was one of many notable female photographers in the 1950s: others include Helen Levitt , Esther Bubley and Lisette Model . These women did the same kind of street photography as their male peers, but were sometimes constrained by the era’s social pressures. When Orkin had children, she became a stay-at-home mother and took photographs out of her window. That sense of containment, and of women’s inchoate yearning, is wonderfully conveyed by Haynes in Carol .

In short, I’d say that Carol deserves the praise it’s received since its world premiere in Cannes. If, as one critic has said , it is “as smooth and cool as marble,” that stylishness is cut through by a constant and compelling sense of unease. “The novel has such a great disquiet and anxiety between the two women,” Haynes said, and that tension roils under the movie’s pretty surface.

In the Q&A session after the movie, I mentioned that this tension never fully erupts in the way viewers might expect. A gun is uncovered early on–a discovery that stokes our expectations, but Highsmith and Haynes don’t follow Checkhov’s rule . I asked Haynes if this quiet bubbling was harder to film than a more overt drama.

Haynes said he’d been struck by how Highsmith writes about lesbianism and crime with similarly violent vigor. “She wished the tunnel might cave in and kill them both, that their bodies might be dragged out together,” the novelist has Therese think at one point. (“When I read that, I thought, ‘Now that’s love,'” Haynes said.) Then he made a cheeky analogy that drew a huge laugh from the audience. “Well, it’s a lesbian gun in the film,” he pointed out. “So it doesn’t shoot.”

———————————————————–

The official movie site for Carol is here .

The schedule for Todd Haynes: The Other Side of Dreams can be seen here .

Find the perfect Patricia Highsmith novel for your personality here .

Buy The Price of Salt here .

See more of Saul Leiter’s work here .

Find out more about Lovers and Lollipops here .

2 comments on “ A Lesbian Gun: Words and Images Inspire Todd Hayne’s New Masterpiece ‘Carol’ ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

I’m looking forward to seeing this new Todd Haynes film. So interesting to learn about the visual influence of Saul Leiter’s photographs.

Many thanks for that article, it was an education. And the thoughtfully curated links were a delight. Nice for us non-New Yorkers to finally be able to follow up a LitLens tip: it is opening in the UK later this week.