The Power of Visual Storytelling: An Interview with Mark Tuschman

In the history of social advocacy, photography has played a key role. It makes sense: a compelling photograph has a visceral impact that goes beyond words. Lewis Hine’s photographs of child workers provided evidence of abuse that led to a change in the law; Nick Ut’s image of a girl fleeing a napalm attack alerted the world to Vietnam’s horrors. In such situations, the cliché holds true: a picture really is worth a thousand words.

In the history of social advocacy, photography has played a key role. It makes sense: a compelling photograph has a visceral impact that goes beyond words. Lewis Hine’s photographs of child workers provided evidence of abuse that led to a change in the law; Nick Ut’s image of a girl fleeing a napalm attack alerted the world to Vietnam’s horrors. In such situations, the cliché holds true: a picture really is worth a thousand words.

Mark Tuschman knows this value intimately. For over a decade, he has traveled across the developing world taking photographs for nonprofits and NGOs. For the most part, his work has focused on disadvantaged women: child brides, sex workers, victims of domestic violence and human trafficking. Throughout, he has felt a great responsibility to tell his subjects’ stories accurately, and as powerfully as possible.

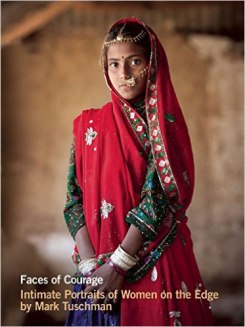

I first saw Tuschman’s images last year on Facebook, where a friend was urging people to support a Kickstarter campaign for a book called Faces of Courage: Intimate Portraits of Women on the Edge . It seemed like an important project, and the powerful portraits moved me. I found myself clicking the ‘Donate’ button.

A victim of human trafficking in Indonesia, Seni was eventually reunited with her husband and young son. Image (c) Mark Tuschman

“I felt I needed to do this book,” Tuschman says. “I was working for NGOs, but hardly any of the images I took were published, so they weren’t being seen by the world.” The month of his Kickstarter campaign was “possibly the hardest month of work I’ve ever done,” he says with a laugh, but it paid off; the campaign was funded. Two months ago, the book—expertly formatted by design veteran Milton Glaser—rolled off the presses.

Beautifully photographed and handsomely produced , Faces of Courage is also an unusually comprehensive book. While Tuschman doesn’t shy away from portraying the harsh realities of his subjects’ lives, he doesn’t present them as powerless victims. In addition to sections on teen pregnancy and human trafficking, there are sections about education, microfinance and vocational training. We see how, with support and encouragement, women can escape the cycle of poverty and repression.

I read that you studied the neurophysiology of vision in a PhD program before you became a photographer. What was it about vision that fascinated you?

I think I was always an inherently visual person, but I took the wrong track initially and studied electrical engineering, computer science and neurophysiology. I had grown up with my grandparents in a tenement house on New York’s on Lower East Side, where I spent a lot of time looking out the window. I read LIFE magazine and looked at the pictures. I was attracted to the work of Jacob Riis, Lewis Hine, Eugene Smith and other social justice photographers.

In rural Guatemala, forced marriage and domestic violence are common. This young girl attends Opening Opportunities, a UNPFA program designed to teach girls the value of education. Image (c) Mark Tuschman

What was your PhD work?

I was trying to figure out how horizontal and bipolar cells in the retina connect and communicate with each other. It was tedious work, and I wasn’t getting anywhere. Then a friend asked me if he could bring me anything back from Hong Kong, and I asked him to get me a camera. I think I gave him $100. Once I had the camera, I started using it. I had a lot of freedom as a PhD student, and I had a beautiful wife and a puppy, so… I picked up Ansel Adams’ books and started teaching myself photography.

So then you decided to be a photographer, and at first you were doing corporate work.

It took about eight or nine years to make the transition to becoming a photographer. First I worked at Stanford and SRI International designing computer programs and writing software for medical applications. I arranged to work part time and spent the rest of my time doing photo documentary work. I had exhibits in San Francisco and sold prints to SFMOMA, but realized I couldn’t make a living as a fine art social documentary photographer. I lived in Silicon Valley, so I became a corporate photographer. One thing that work taught me was to see things quickly, and compose and light them. You might only get 10 minutes with a CEO, but you had to go in and get the shot; there were no second chances. I was always trying to tell a story with a single image. Conveying emotion was a key part of that.

How did that grow into nonprofit work?

I was doing the corporate work, and it was feeding my wallet but not my soul—it wasn’t my dream. So I was always trying to find personal projects. Maybe because of where I grew up, I wanted to use photography as a way to highlight issues. I did some local projects, then a friend arranged for me to go to Ulan Bator, Mongolia, in 2001, with the Global Fund for Women. There, I visited a safe house for physically abused women, which affected me deeply. It was down a dirt alley, and inside there was a small room with bunk beds. I was told stories that were horrific, incomprehensible—about women beaten and literally starved to death. After that I started working more for nonprofits, and that motivated me to do the book—because so few of the images I was shooting were published and seen.

What’s it like, as a man, to go into such sensitive situations?

I never even think about that, honestly. I always feel I’m there for a good purpose, to expose what these people are going through, and I never think of myself as a man who’s imposing myself. I don’t think the issue of violence against women will be solved until men take a firm stance against it. It shouldn’t be a women’s issue or a men’s issue, just a human rights issue.

A lot of the work in the book is about women’s healthcare, and what happens when they’re refused access to it. Why was that key?

Having access to reproductive healthcare and contraception is so fundamental for a woman to make decisions about her own life. When women don’t have that access, a lot of them suffer and die. And there are lots of countries where women lack access to the most basic healthcare. Even in this country, people are trying to de-fund Planned Parenthood, which makes no sense to me.

There are also hopeful stories in the book—like the one about Farida Mussa, an English teacher who grew up in a slum, and other women who’ve been helped by microfinance loans. They’re the lucky ones. Do you see hope for the future in their stories?

I do. I think if you can give people a little bit of hope with supportive programs, it makes a huge difference in their outlook. I saw that with the microfinance program I documented in Ghana, which made as much difference psychologically as it did economically. Once the women felt they could get enough money together to keep their children in school, it lifted their spirits and the community.

You said you want to convey emotion in every image, whether for corporate marketing or social justice. How do you do that?

You’re trying to get a sense of a person’s depth, their soul. When I teach, I always say that light has an emotional quality, a spiritual quality. Before I used digital equipment I would shoot outdoors in natural light a lot, but in Africa, where the sun is bright and harsh, you often have to avoid the outdoors. We’d go inside, somewhere with a porch or a window with light streaming through, and it had a beautiful quality to it. Digital photography has given me more latitude to shoot in low-light conditions.

But it’s more than that, isn’t it? You have to make a connection with your subject, establish trust.

I always did this work in conjunction with an NGO or foundation. Often, the trust the NGO has earned gets transferred to me. But it’s also a question of your approach and energy. I come to subjects with an attitude that I am going to make a special photograph, that they are important and we are not going to rush. Instead, we are going to create something exceptional that will tell a story. I think my confidence that I can do this gets communicated in a non-verbal manner. Creating empathy with your subject will go a long way in creating meaningful images.

Rather than going the traditional route, you decided to launch a Kickstarter campaign to get your book published, which is becoming a popular option for photographers. Tell me about that.

It wasn’t my first choice. At first I spent years trying to raise money on my own, but I’m a terrible fundraiser. I figured I had a lot of pharmaceutical clients and they’d support the book—but I realized that the book tells a very broad story, and the companies wanted to narrow in on a single aspect. So that didn’t work. I thought I’d find a philanthropist or a women’s NGO, but that didn’t work either. I tried traditional publishers, but the few who wanted to do it wanted me to put up money up front—like a vanity press. One publisher wanted $80,000! Meanwhile, everyone was telling me about Kickstarter. I knew it would be hard work, with no guarantee of success, but I decided to do it. We launched the campaign in July, 2014. It was a huge undertaking. You need a good site to start with, and a big social media presence; I even hired a Twitter avatar. People said my video was too long at ten minutes—but the people who watched it responded well. The campaign got funded. I didn’t want to go to Kickstarter route, but it turned out to be the best thing I could have done.

Microfinance loans have helped women like Ghanaian Evelyn Quartey, who is now a distributor of flour. Image (c) Mark Tuschman

So the campaign gets funded. How do you go about getting the book produced?

I’d done some work for the great designer Milton Glaser, and I have a friend who works for Milton in New York. I asked Milton if he’d design the book, and he agreed. He and his lead designer, Sue Walsh, worked on it, and I had a lot of input. I think they did a wonderful job. We went with Topan printing, a great printer in Hong Kong. We tried to use the best quality paper and do a first class book.

People who read the book might want to know how they can contribute to some of the causes you highlight. What would you say?

I think it depends on the individual. I list a bunch of organizations at the back of the book. People can donate money, they can get active in the organizations, or start their own nonprofit. They can write, take photographs, go and create some NGO somewhere. It’s up to each person to respond in his or her own way.

Mark Tuschman speaks at the World Affairs Council in San Francisco in October 2015. Image (c) Robert Kato

Other than selling this book to individuals, what’s your plan for it?

I want to get the book into schools, because that’s one of the ways of creating activists. I’ll certainly send copies to local high schools, and I’d like to get it into libraries too. One friend told me I should send the book to the Pope. I would do that! If only I knew how to get it to him…

———————————————————————

To buy Faces of Courage , click on the image below.

10 comments on “ The Power of Visual Storytelling: An Interview with Mark Tuschman ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Wow…I came for the images, but your story is incredible.

Thank you, Wabi Sabi. Your comment is much appreciated!

Wonderful interview and amazing story. Just ordered the book.

Thanks, Michele! Enjoy the book.

Thank you for your sharing!!

good interview, like this post, thanks for content

An amazing interview!! A photograph becomes a portrait only when it has meaning to it!! 🙂

What a read! Thank you for sharing

https://greenwichlane.wordpress.com

I work as a public school teacher. You can share the book with my class.

Really nice pics. Also cool story behind them.