Heart of the Matter: An interview with Glenna Gordon

In northern Nigeria, being female can sometimes be a risky proposition. In this patriarchal, Muslim-dominated society, one of the better options for a girl is to enter into an arranged marriage: worse ones include being trafficked, kidnapped or raped. In April 2014, the northern Nigerian town of Chibok became world-famous when radical Islamic group Boko Haram (whose name means “Western education is forbidden”) kidnapped 276 schoolgirls. The girls never returned, despite international outrage and an online campaign, #BringBackOurGirls.

In northern Nigeria, being female can sometimes be a risky proposition. In this patriarchal, Muslim-dominated society, one of the better options for a girl is to enter into an arranged marriage: worse ones include being trafficked, kidnapped or raped. In April 2014, the northern Nigerian town of Chibok became world-famous when radical Islamic group Boko Haram (whose name means “Western education is forbidden”) kidnapped 276 schoolgirls. The girls never returned, despite international outrage and an online campaign, #BringBackOurGirls.

News like that tends to color our view of a region and a society. So it’s heartening and wonderful to see Glenna Gordon’s new book Diagram of the Heart , which documents the lives of female Muslim romance novelists in northern Nigeria. Wait, you might be thinking at this point, did I read that wrong? No, indeed not. Unlikely as it may seem, there is a thriving group of Muslim women romance authors in northern Nigeria.

Balaraba Yakubu, whose 1990 book Sin is a Puppy that Follows you Home is one of few Hausa novels to be translated into English. Image (c) Glenna Gordon

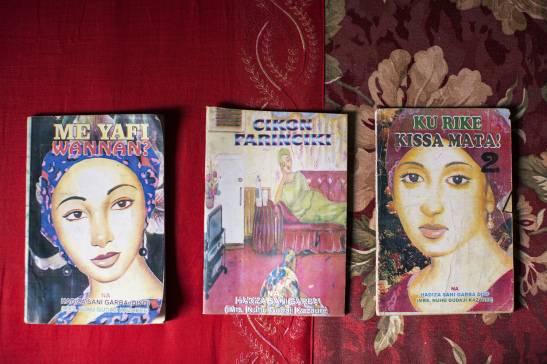

The novels, which are known collectively as Littattafan Soyayya (“love literature”), are sold in local markets and on home-to-home visits. Printed cheaply on thin paper, they are sometimes serialized, with each volume costing a modest one or two dollars. “The term Littattafan Soyayya is a bit misleading: it covers up the fact that there’s a huge diversity within the novels,” says Carmen McCain, an academic in Nigeria who served as the translator for Gordon’s book. (McCain points out that men have their own books, which tend more toward adventure and detective fiction, but that some women read men’s books and vice versa.) The most popular of the women novelists are minor celebrities, and might receive hundreds of phone calls a week from fans soliciting their advice on a personal matter.

Photographing these women, and getting a sense of their lives beyond their writing, was a challenging task for Gordon. The women have restrictions on leaving their homes, and many are wary of being stereotyped by the western media. Gordon had to navigate their diffidence while also looking out for her own safety in a place where women were not expected to travel independently. “I would go out to see the women but I wouldn’t just go to the ATM, or to buy a soft drink on my own,” she says. “My goal was to minimize risks.”

It’s all the more remarkable, then, that Gordon managed to put together a book that puts Littattafan Soyayya into context, delving comprehensively into the lives of women in northern Nigeria. From individual courtships to mass weddings, from censorship police to a Jane Austen-loving writer, Diagram of the Heart goes beyond stereotypes of Islam to tell the story of a colorful and complex society.

First of all, I want to say that I appreciated the size of your book. It’s only slightly bigger than an average paperback, which makes it feel very intimate, and I think that size matches the subject matter perfectly.

Thank you! When I started the book project, one of the first things I felt strongly was that it needed to be a small book. I wanted to echo the way the novels by these women in Nigeria felt. Big photo books have sort of a formality to them that I didn’t want this to have. After all, Diagram is all about books that are small and cheaply made.

How did you first come across this group of Muslim women novelists?

I’d been working in Nigeria for some time, and while in Lagos I was working on a personal project about weddings called Nigeria Ever After I heard about a mass wedding in the north. Before going there I emailed an acquaintance, Carmen McCain, who’s an academic in Nigeria, and asked what I should read to prepare for the trip. She recommended a novel called Sin is a Puppy that Follows You Home , a romance novel by a Muslim woman that had been translated from Hausa. I remember thinking, What? What ? I was super excited about it.

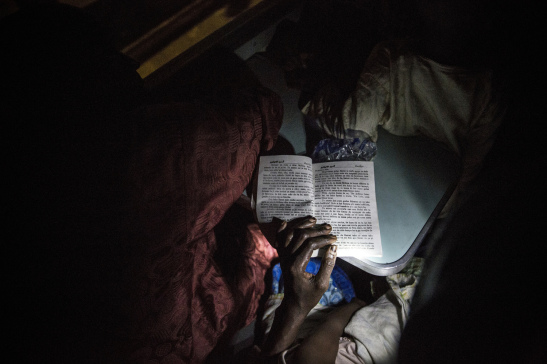

A woman reads a Hausa romance novel using the flashlight on her cell phone on a train crossing Nigeria. Image (c) Glenna Gordon

I’m not surprised. The whole concept of a female Muslim romance novelist seems like an oxymoron. What are these novels like? Are there parameters for them?

There’s a wide spectrum. They’re written in Hausa, the language in northern Nigeria, and since I don’t speak Hausa, I’ve only read the few that have been translated. But generally they’re somewhere in between morality tales and romance novels. Some are very conformist and are about how to be a good Muslim wife; others are more subversive and might take a stand against things like child marriage or human trafficking.

Are there repercussions for women who chose to write books?

Yes, I think so. It’s definitely an unconventional choice for these women to be writers. Some people’s husbands are happy with them because they make good money, but others aren’t. I met one woman whose fiancé’s family didn’t approve of her writing, and they broke off the engagement: now she’s a thirty-year-old spinster, which is kind of the end of the world for a woman in northern Nigeria. A few years ago the then state governor of Kano publicly burned many romance novels and said they were corrupting the youth. He’s now the minister of education in Nigeria.

Is there solidarity between the women? Do they meet up?

Yes, most of them know each other, and they have meetings every now and then. There’s a group called the Association of Nigerian Authors that’s open to both men and women: it meets regularly in a library, but since women are often expected to stay at home in northern Nigeria, that meeting is mostly men. The women writers have another association called Mace Mutum (which roughly translates to “Woman is a Person,”) and they have a weekly meeting on Facebook.

One of the writers, Amina Hassan, is a fan of Jane Austen. Do you know how she discovered Austen’s novels? And how connected are women in Kano to Western ideals of love and marriage?

I don’t know how she was first exposed to them, but she has a day job as a schoolteacher and I know she thought of Austen as a predecessor of sorts. Many of these women use the Internet and watch American TV shows, but at the end of the day, Kano is still very much its own place. When I first got there, I was excited about meeting women who I thought shared values with me—but as I stayed longer, I learned the limits of that. One novelist spent a long time trying to persuade me to become the second wife of a government lawyer. I thought, Ok, this is where we’ve reached our wall. We can drink juice and hang out, but at the end of the day I’m going to go back to a world where I make my own choices and she lives here in Kano, where being a second wife is considered a good choice.

Some of your titles are quite enigmatic. One image is called, ‘The quiet violence of arranged marriage.’ Can you talk about that?

I was trying to find space for the images to breathe without being too specific. Relationships are complicated: the girl in that image was sad to be leaving her parents’ house, but at the same time, she had made a relatively good match. I don’t know what her relationship is going to look like, and neither does she. But in the case of this arranged marriage, it was a middle-class girl making a good match. At the moment when I took that picture, she looked very sad, but at other moments, she looked pretty happy. Maybe her husband will beat her every night and maybe he will be a doting spouse, but we don’t know. I wanted it to be ambiguous, and to capture the sadness of the end of one part of life and the start of the next.

What does that ambiguity say to you about Islam?

The ambiguity in my images hopefully reflects a complicated and multifaceted world we live in – whether we’re talking about feminism, Islam, or narratives about Africa. Many people have preconceived notions about it that are not grounded in learning or knowledge – myself included. Doing this work mainly taught me how much I don’t know. If you think about Christianity in America, there are so many iterations — from a Quaker living in Pennsylvania to a member of the KKK in Texas. They all fall under the same umbrella term even though we’d never consider them the same, and yet when we think about Islam, we group so many totally different groups together into one ideological monolith.

A woman poses for a portrait at the Office of Enlightenment at the Hisbah, the Islamic morality police. Image (c) Glenna Gordon

In order to put Littattafan Soyayya in context, you photograph the society around the women: we see a mass wedding, the local censorship office (called the Hisbah) and women at prayer. It’s a segregated society with a lot of rules. Are there any love marriages?

Most marriages are arranged, but different families allow different amounts of autonomy in terms of how much choice the woman can make. It depends on the family’s worldview, economic position, and ideas about marriage.

Do you think that this literature has had any discernible effect on the society there?

That’s hard to answer. When NGOs go to a place like northern Nigeria, they’ll have a goal. They set up programs and look for measurable effects. But often change isn’t so straightforward, especially when a directive comes from outside of the community. But for women to be writing novels in a place like this is huge. There are women speaking out against child marriage who have experienced it first hand, and there are young girls I met who want to grow up to be writers. The changes might not line up to the yardsticks of cause and effect that we generally look for, but they are happening and they are meaningful.

—————————————————-

Buy Diagram of the Heart here .

Visit Glenna Gordon’s website here .

Further reading: a fascinating article on how Nigerian romance novelists sneak feminism into their plots .

6 comments on “ Heart of the Matter: An interview with Glenna Gordon ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Wow. The pen truly can be mightier than the sword.

This is such an outstanding story, excellent writing, great research and personal details, great questions. And did I mention the fabulous photos?! My fav is the woman reading under the covers with a flashlight. Truly Pulitzer material here! I feel privileged to have read and seen this. Thank you for enlightening and inspiring me!

An insight into another world. Too often we stereotype people but the line “The ambiguity in my images hopefully reflects a complicated and multifaceted world we live in – whether we’re talking about feminism, Islam, or narratives about Africa.’ should make us think again.

I was arrested by the image of the cover of “Ku Rika Kissa Mata!” which reminded me of those portraits on Roman-Egyptian coffins – another insight into another world and the many facets of Africa.

Great interview, Sarah.

I loved this amazing history ❤ follow me 😉

I love this. very inspiring to me, an aspiring writer.

The best history I have read by far!