Mission Total Immersion: Laura Poitras at the Whitney

Would you like your art with a side of politics, or your politics with a side of art? You don’t really have to choose at Astro Noise , a new exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art . Astro Noise is the first solo museum show for Laura Poitras, better known as the documentary feature director of a trilogy of political films about post-9/11 America: My Country, My Country , The Oath and last year’s Oscar-winning Citizenfour .

As someone who’s always been interested in art that takes on sociopolitical issues, I was eager to see this show. I’d been surprised to learn that Poitras was a visual artist as well as a documentary filmmaker, since the two disciplines require different skill sets and preoccupations. Knowing her reputation as a daring investigative filmmaker, I was intrigued to see what she would come up with as a visual artist.

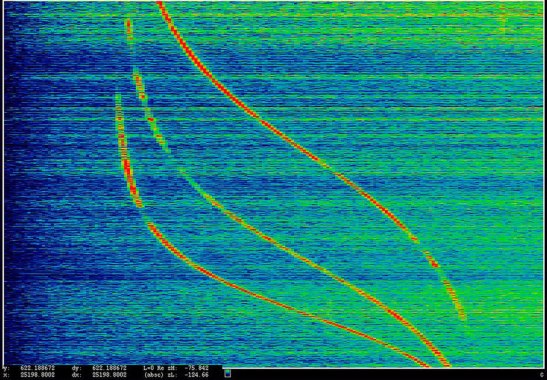

ANARCHIST: Power Spectrum Display of Doppler Tracks from a Satellite (Intercepted May 27, 2009) , 2016. Courtesy Laura Poitras/whitney.org

Let’s just start by acknowledging that it’s a bold move for the Whitney to have given Poitras this show. Through her 9/11 trilogy, she is known as one of the fiercest cultural critics of America’s war on terror. Citizenfour (the only one of her films I’ve seen) documents the consequences for her of being chosen—along with The Guardian ’s Glenn Greenwald—as Edward Snowden’s channel for his explosive revelations about the National Security Agency. While the film isn’t a polemic (Poitras describes herself as a journalist rather than an activist or advocate ), it can’t help but be sympathetic to Snowden’s cause, simply by portraying him as a thoughtful young man who understands the risks of his actions.

Poitras herself has been targeted by the U.S. government, which placed her on a watchlist in 2006 for purportedly suspicious activities while she was filming in Iraq. (She subsequently moved to Berlin, where she could conduct her work with less state interference.) By giving her this show, the Whitney (which has been in its new, bigger location for less than a year ) seems to be making a statement about government heavy-handedness and free speech, and announcing its intention to be topical and provocative. I can’t remember a museum planting a flag so squarely in hot-button national politics in recent times. I hope the Whitney isn’t counting on any money from the National Endowment for the Arts any time soon.

While the show isn’t a direct call to action, it is definitely provocative. Poitras has said that she wanted to create “an environment… that challenges the viewer to engage emotionally, physically and intellectually” and to “actively consider their position and responsibility in the ‘war on terror.'” This is done through a series of installations that (to use a buzzword) are “experiential”—with giant screens, soundscapes and darkened rooms triggering intimate engagement between viewers and the material. In most cases, wall text is minimal: this is an exhibition that relies first and foremost on the visceral power of images to stimulate the limbic system.

On one side of O’Say Can You See , footage shows people looking at Ground Zero after 9/11. Image (c) Sarah Coleman

That’s done most effectively in the opening installation, O’Say Can You See , in which a huge double-sided screen hangs in the middle of a darkened room. One side shows slow-motion footage of people looking at Ground Zero in the weeks after 9/11; the other features U.S. military video of two prisoner interrogations in Afghanistan, shot during the same period. The contrasts between the two sides are extreme: from color to black and white, from focused gazes to the loss of sight (when a bag is placed over a prisoner’s head). The faces “capture a moment in history at a crossroads,” Poitras says, where “many different paths could have been taken.” Seeing them with hindsight is an exercise is ‘what if’ mournfulness: we all know which path was taken, and with what results.

The other side of O’Say Can You See shows footage of two prisoner interrogations in Afghanistan. Image (c) Sarah Coleman

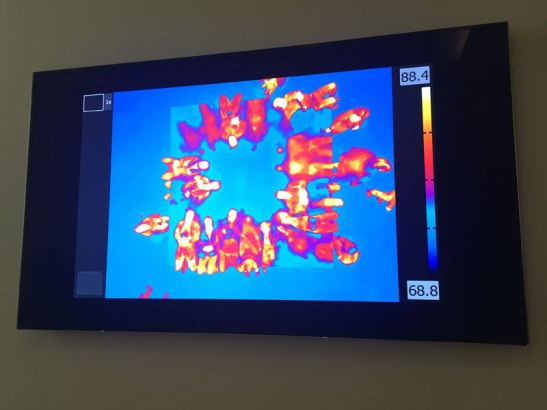

In another room, Bed Down Location , viewers are encouraged to lie on their backs on a padded platform and gaze up at a projection of the night sky in three different countries: Yemen, Somalia and Pakistan. At certain points, flares streak across the night sky, evoking shooting stars, and the exhibit plays with the tension between this beauty and the real purpose of the flares (they are actually the paths of military drones). It’s a clever conceit, and there’s another clever layer added in the final gallery, in which a screen displays an infrared image of people’s bodies on the platform—a reminder that we are all constantly being monitored.

In the final gallery, a screen shows an infrared image of people watching Bed Down Location . Image (c) Sarah Coleman

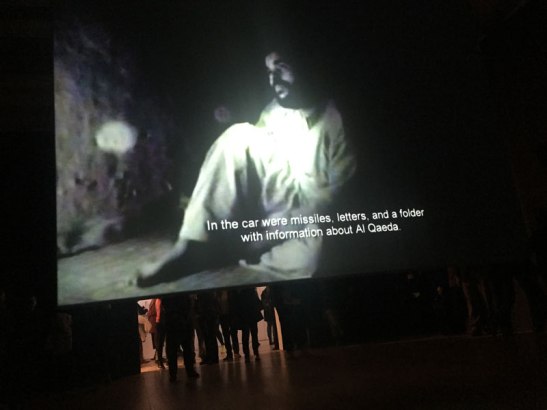

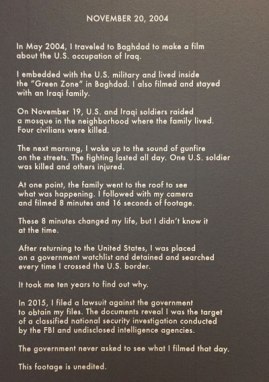

But perhaps the most devastating—and most pointed—installation is the one that is most personal. In November 20, 2004, Poitras delves into her own history as a “person of interest” to the U.S. government. The exhibit displays redacted documents from her F.B.I. files (which she obtained through a Freedom of Information lawsuit) and the eight-minute film footage that initially aroused the F.B.I.’s concern.

The footage—which seems utterly benign—is shot from a rooftop in Baghdad, where Poitras was staying in the Green Zone with an Iraqi family. The previous day, U.S. and Iraqi forces had raided a mosque in the neighborhood and four civilians were killed. In the video, we hear the gunfire of a retaliatory attack against the military, and one of Poitras’s Iraqi hosts remarks, “These Americans are a curse.” According to the F.B.I., this was enough to determine that Poitras “had prior knowledge of the ambush and had the means to report it to U.S. forces; however, she purposely did not report it so she could film the attack for her documentary.”

As Poitras points out in a wall text, “the government never asked to see what I filmed that day”—instead, it subjected her to detentions, searches and intense surveillance. By showing the footage, she is both clearing her name and exposing the heavy hand the U.S. government brought to bear on one of its own citizens. It’s a damning indictment, presented in the most straightforward terms. Even the language in the wall text is plain, neutral, informative—which ultimately makes it more devastating.

At this point, it strikes me that there are two salient questions to ask about Astro Noise . First, does this kind of material belong in an art museum? Second, how does the exhibition work as a delivery system for the same kind of questions that Poitras explores in her films?

On the first question, I have to admit I’m biased: I believe art should take on the major issues of the day, so I have no issue with Poitras being given a show here. Perhaps I’d feel differently if she’d simply framed a bunch of government documents—but she has worked hard to conceptualize ways to present the material in unique, original ways.

That said, the very strength of the exhibition (its unique presentation) might also be its Achilles heel. Why? Because there is something of a trend these days for museums to mount dramatic, immersive shows that transport viewers emotionally. Such shows—whether they involve titanosaurs or viewers on swings —rely on spectacle to pull in crowds looking for an ‘experience.’ (For fine art photographers, the market pressure to print work at billboard size has become so huge that it’s something of a radical act to decide—as Gregory Crewdson did in his current exhibition —to produce prints no bigger than the average flat screen television.)

Viewers look through slits in the wall at government documents and video in Disposition Matrix , another exhibit in Astro Noise . Photo (c) Sarah Coleman

Such shows can be fantastic fun, and intense—but does that translate to a deep intellectual encounter? The problem I often have with conceptual art is that its content can be eclipsed by its concept, either because the concept is so flashy or because it is confusing—sometimes both. It can also feel emotionally distant, usually because the artist is absorbed in some kind of PoMo dialectic that only six other people understand.

Astro Noise might suffer by association with shows of this kind, and might lead some viewers to shrug and say, “I don’t understand this.” Personally, although I found it fascinating and challenging, I can’t say (unlike I can with Citizenfour ) that it provoked huge outrage or inspired me to read up on government surveillance. The exhibit that came the closest to doing that for me was actually the simplest and least ‘arty,’ November 20, 2004, which—because it relied on personal narrative and disputed documentation—was the most intriguing.

Other people will no doubt feel different, though—and I respect Poitras’s attempt to reach a new audience on a direct, visceral level. If even a small percentage of the viewership for this show comes out of it moved, outraged and/or better informed, I think her experiment will have been well worth it.

3 comments on “ Mission Total Immersion: Laura Poitras at the Whitney ”

Leave a Reply

Connecting to %s

Dear Sara-

I like this article very much! It looks this show really deserve to be seen for many reason. It is very interesting what you write in it and, in particular, what you write about the museum’s tendency to count on spectacle “to pull crowds looking for an experience”. So true! From the article I can see you are pretty busy with the art shows (good fr you) and I am happy to immagine you going up and down for NYC following the art city life. How are you? And your kids and your husband? A big hug Paola PS I’ll forward a Sasha Wolf email from which you can download tickets for Art on Paper ( at the bottom). I went last year and it was a small but nice fair.

I don’t totally agree. I found Astro Noise more gripping and immersing than the CitizenFour movie. I never though to classify Astro Noise as “conceptual art”, and just took it as a subversive use of a (very nice) art gallery to present some thought-provoking documentary material. The exhibition was direct and to-the-point. Very glad I went, and thanks for suggesting it.

Thanks, colmenareno. I’m glad you felt differently. I take your point that actually, the conceptual element was not the most important thing. It was definitely an interesting “delivery system” for this material. I think maybe I liked it more than my review implies, but one has to make an argument!